Even in his devastating critiques of high-modernist central planning, James C Scott acknowledges the benefits to planning and the levels at which it can occur with relative safety. The author M Black also challenges us not to fetishize decentralization in such a way as to ignore the benefits of non-coercive degrees of centralization. So some degree of planning should exist. There seems to also be general agreement between all of the authors that some complexity and scale based obstacles exist to central planning, even in less centralized forms. From that point we can debate where these lines are.

I will continue to advocate that we intentionally build out multiple competing/cooperating social welfare planning measures up to and no farther than our limits and simultaneously explore the problem space of different value signal feedback loops such as markets. This approach of testing a wide range of planning and value signal coordination approaches follows the line of thinking in Kevin’s sentiment of “Let one-hundred flowers bloom.” As Aurora’s essay is the one most directly opposed to my approach I will focus on challenging its claims and incorporating its advancements in the theoretical development of a Maximum Viable Economic Planning measure. Comprehensive integration of this limit should form the basis of any model for a new economy or array of overlapping new economies.

Challenging Aurora’s Assumptions

Beautifully integrating and generating novel insights from the fields of complexity science, network science, information theory, and neuroscience Aurora offers what I am not shy to say is one of the most substantive advancements in mathematical anarchist (communist) thought. It faces boldly the problem of scale in non-hierarchical systems in ways that few others have even attempted. It must be read by anarcho-communist theorists and must be seriously contended with by people in P2P spaces, libertarianism, social ecology, and other decentralized economics as well as being of interest to mathematicians, computer scientists, and economists more broadly. It’s fascinating and a joy to read. However, while its contributions are substantive, it suffers from several critical failures and other weaknesses which could be strengthened through future work. The contributions it does offer though help to elucidate a more robust measure of Maximum Viable Economic Planning which should be the basis for any conversation about planning, decentralization, and economic coordination.

The basic premise of the piece is that the optimization of economic coordination through the profit mechanism in markets should be replaced by an optimization of complexity through cooperation. Aurora parses several of the major advancements in related fields to settle upon a proposal that optimizes for “integrated complexity” utilizing an effective complexity measure built into a network analysis. One should take a moment to truly consider how beautiful that is on its face. It offers much to the problem of coordination, a shared metric for optimization of ideal quantities in a supply chain, which is a major area of contention in the calculation debate.

While this is a deeply intriguing view of societal evolution in general, and decentralized economic coordination in particular, it absolutely does not replace or solve against markets in the way the author assumes it does. The critical failures are as follows:

The substantive open problem of revealed preference and discovery in economics directly undercuts the viability of this proposal for large scale economic coordination. This issue was covered in some depth by the essays of myself, Gillis, and Miroslav as well as in great depth, if from a more liberal perspective, by Don Lavoie in many of his books but notably in Rivalry and Central Planning. There are also interesting parallel spaces of exploration using technology such as Holochain, as mentioned in the article by Sthalekar.

Relatedly, this essay does not actually deal with any of the practical issues of economic coordination such as, centrally, supply and demand. It claims to supplant Linear Programming but does not accomplish the basic feat that LP does. It does something more interesting but it does not solve supply chain optimization. The algorithm proposed would be better suited for analyzing possible modes of societal and economic evolution rather than serving as a practical replacement to markets at the material levels. However, optimizing such evolution is also a task that markets freed from capitalism and monopoly rents can accomplish, as shown extensively in the various works most commonly associated with C4SS as an institution. This proposal could be thought of as a value vector creator for which something like Linear Programming could then optimize the ideal proportions of labor for. If that is the case though, all the critiques and limits of Linear Programming to central planning still apply to this model.

The claim that this algorithm replaces the need for subjective value measures overall is completely unsubstantiated with some disturbing possible implications. Even capturing the raw input measurements for maximized integrated effective complexity does not skirt the problem of accurate input information unless the author (which I doubt) proposes some form of massive surveillance architecture to capture the information needed for this form of cybernetic coordination.

While I will not go into it in-depth here, the author takes a very naive view of markets as automatically generating capitalism, exploitation, and massive unequal accumulation. She does not adequately address the wide arrange of known and unknown spaces of exploration around exchange such as but not limited to, left-market anarchism, mutualism, Georgism, and value-signal employing P2P systems. The author does not show a depth of understanding of the critiques of these and other schools of thought that are anti-capitalist but pro-market. Most importantly, she does not understand the types of countervailing and centrifugal forces that C4SS has long labored to explore in the process of resisting the formation of capitalism while utilizing some of the benefits of exchange. Her knee-jerk response to markets as automatically leading to capitalism is a common one because it makes some sense at the surface level (coming, as I did, from the left it was a hard pill for me to swallow). However, as a wide range of subsidies and artificial economies of scale have distorted and made myopic our visions of what is possible, it’s the duty of the anarcho in anarcho-communism to bravely facedown groupthink in the pursuit of root dynamics and mapping the wide space of possibility.

These issues are extremely nontrivial. They do not, however, minimize the overall contribution of this work, but rather call into question some of its central premises about what it can and cannot accomplish. This all being said, the contributions of this essay are also extremely non-trivial, even to, and this may dismay the author, the study of mixed market and planned decentralized economies. Indeed it offers a great jumping off point to further develop a theory of Maximum Viable Economic Planning.

Finding Our Maximum Viable Economic Planning

The transition involved in realizing a new ideal economics will involve a central conflict between those efforts devoted to expanding the non-market spaces of mutual-aid and social welfare and those innovating through the various internally competing and cooperating exchange nexuses. While this space of contestation will be dynamic and complex, as it already is, with constant new innovations blossoming in the cracks, we can build some structure now in order to reduce harm while we explore the problem space. So while Belinsky discusses Minimum Viable Economic Planning, I argue that one form of harm reduction for exploration is developing a sense of the Maximum Viable Economic Planning Limit.

The basic point to understand is that our ability to plan should be greater than or equal to how much we are currently relying on planning. A high level and deeply simplified overview would look like the following:

Model rate of complexity processing >= Required rate of complexity processing

However to engage with non-math audiences as much as possible we can break this down further:

model = complexity / time

Think of this as a rate like miles per hour. It’s essentially a rate of computation within some constraints. An example would be model = 10 bits per millisecond or something like that. The model can be anything from linear programming on a certain array of computers or a direct democratic system of federated councils.

actual model > target model

The actual model is what we’re currently capable of doing. This idea is agnostic to how you’re solving the planning (ie linear programming, deep learning, councils, or whatever). This is saying if we use this type of algorithm to solve this problem we have right now, this is what our rate of solving it will look like.

The target model is what rate of solving the problem we need to have. For example, how many linear programming variables we need to compute in a certain amount of time to make sure a million people don’t die from not getting a vaccine.

The actual model must be greater than the target model or it will be failing to reach the demands placed on it.

actual model = target model

When we set it up this way you can solve for either time or complexity in the actual model side by making the other static and making it an equality. So say:

target model = 1 bit / 5 milliseconds

actual model = 1 bit/ 10 milliseconds

Clearly we need to either double the amount of bits we can process or half the amount of time we can process it in, if we want to produce the type of robust social economic coordination plan we need to thrive.

This simplified model of rate of computations compared to what we need to ensure everyone gets fed makes the problem of scale more stark. We can reduce the amount of complexity we need to produce or increase our computational methods or infrastructure. The major contribution of Aurora’s work is to help us define a compelling measure for economic (“integrated”) complexity that we could incorporate into an MVEP calculation in order to face soberly our computational limits. Though this does not solve the other issues related to her proposition, it opens the door for a whole new field of inquiry building on both this and her work. For example, teasing out what this MVEP inequality would look like with more robust measures on complexity, could help us gain a more nuanced view of the possibilities inherent to our given model, and, as Aurora mentioned, optimize towards more complexly interconnected and sustainable societies.

Communication Layers and Discovery

Once we’ve established this basic theoretical grounding it starts to get even more complex. The alternative to tankie style central economic planning is what’s called local knowledge which is a way of decentralizing and parallelizing the problem by relying on individuals to make the best decisions they can about their own domains and then things roughly maintain a dynamic (dis)equilibrium.

My suspicion is that as you move closer to local(decentralized) knowledge your target rate of computation decreases because you can parallelize. But if the Austrians are correct, and I imagine they are about this even if their conclusions are weird, then that is not a linear descent. A locally embedded human mind can solve exponentially more than a broken down super-computer. This means that local knowledge has more computational power overall by parallelizing the problem. This is explored to some extent in Bilateral Trade and Small World Networks by Wilhite where he looks at different nested scales of trade networks. Through agent based modeling he shows how: global trade networks require high search resources but are able to find an optimum, local trade networks require low search resources but are not able to find an optimum, and hybrid networks allow for some leveraging of both local and global coordination knowledge. This could suggest that some planning can help a hybrid model allocate resources most optimally while leveraging local knowledge at the same time. While planning and even direct democratic consensus have complexity limits, this does not eliminate its utility in total. What’s more, there are situations in which the high context information provided by deliberation, as opposed to the stripped signals of prices, can be more beneficial. An unintended hypothetical proof of the hybrid model is how a locally planned social safety net can be locally optimal if not globally optimal, but nonetheless can help provide the basic needs of a community to better prepare them to engage in complex global coordination ie. If you aren’t starving to death you are more likely to be excited to build pro-social supra-local collaboration.

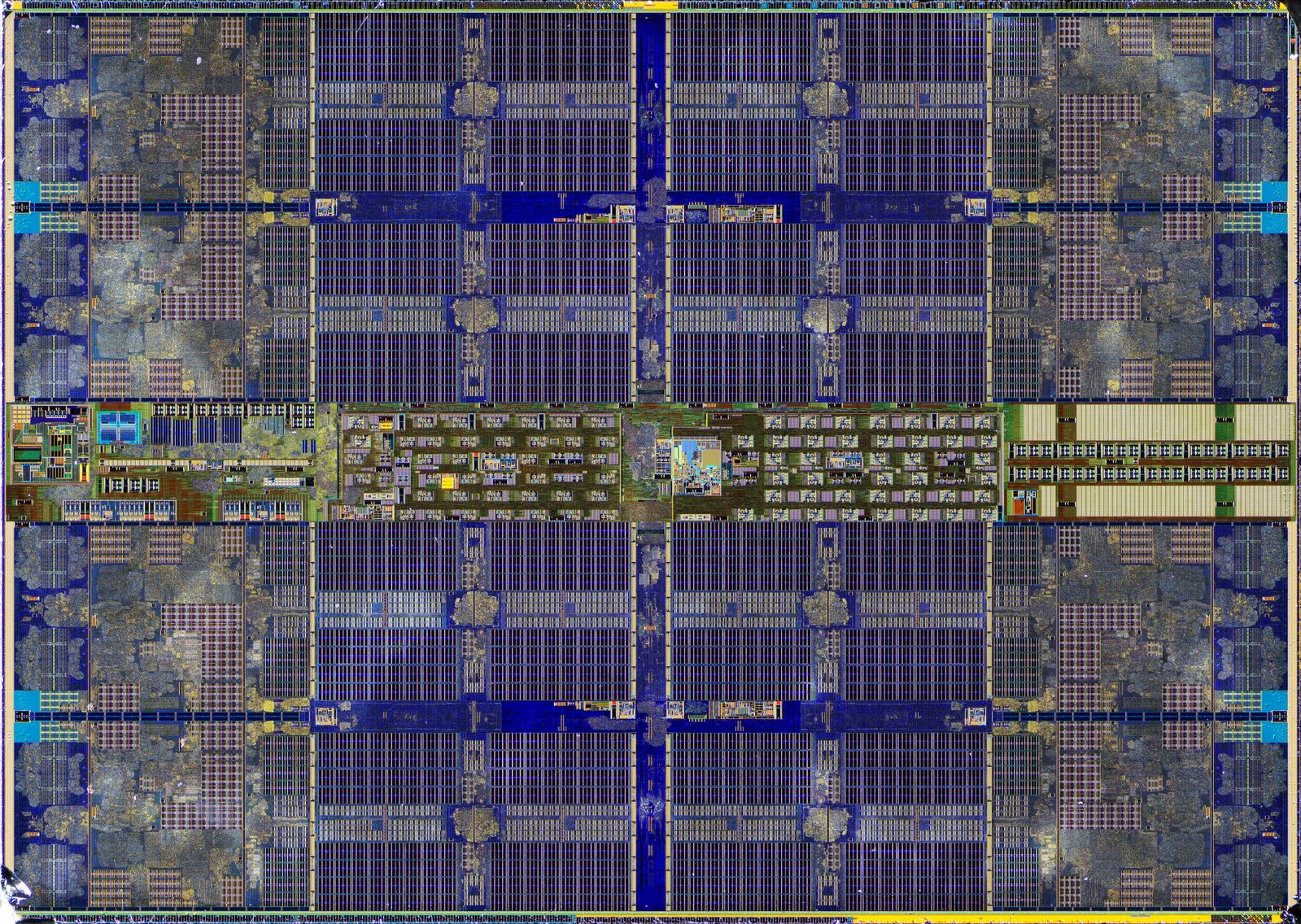

(technical section) This idea can be expanded by looking at how computation actually happens in a computer as well. The following picture is an AMD microchip. Most of what you see in this microchip is actually memory caches and connections. The logical computation is essentially free. What is expensive are all the interconnects required to move data around. In this way, even the computer that is expected to solve our coordination problems faces similar computationally expensive dilemmas of mitigating Shannon entropy of communicating preferences at different scales. This is why when trying to write high-performance software, the first thing to do is to maximize data locality and minimize communication. This logic also applies to all methods of coordinating an economy, not just those that rely on a microchip.

Looking into the technicalities of applying super-computation to problems of (decentralized) economic coordination will help us to more accurately model what is possible and gauge our risk-taking proportionately. Similarly it allows us to break down the problem into more computable chunks or incorporate innovative overlaps with non-decentrally planned networks of cooperative exchange.

Linear Programming

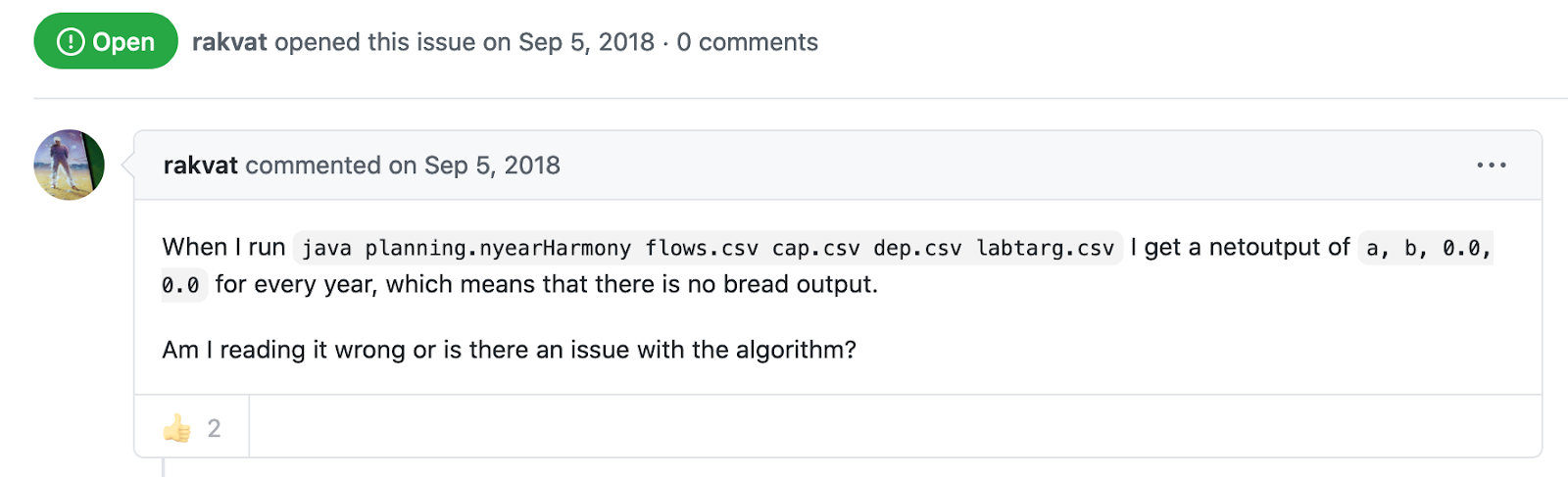

Most of the non-market based models including among the decentralists, knowingly or unknowingly, rely on the contributions of Cockshott and Cottrell as proof of the calculability of economic planning and coordination through Linear Programming. There is much to be said about the nature of their models overall but suffice it to say that the actual code that people think solves all of these hard problems is a messy old Java repo with multiple years old unresolved pull requests and an open issue declaring “there is no bread”:

A dusty Github issue on Cockshott’s 5 Year Plan code stating that “there is no bread output”

Cockshott’s assumptions in this regard can be seen in the way he teaches this topic in that he, like Aurora, claims that cybernetics and the internet solve these problems:

- The Internet allows real-time cybernetic planning and can solve the problem of dispersed information – Hayek’s key objection

- Big data allows concentration of the information needed for planning.

- Super computers can solve the millions of equations in seconds – von Mises objection

- Electronic payment cards allow replacement of cash with non transferable labour credits

This, of course, similarly fails to address problems of discovery and revealed preference, while also relying on problematically simple notions of a labor theory of value which he describes at more depth in “Calculation, Complexity, and Planning.” It is no surprise then, that he is also anti-sex worker, as he sees the whole world through this simplified view of labor that is not even universally accepted among Marxists. Similarly, the issues of computation I have raised in this and my initial paper further challenge his hand-waving magical thinking about Big Data and Supercomputers. It is with an odd parallel to Hayek’s absurd insistence that Pinochet’s authoritarianism did not violate his principles of local knowledge, that Cockshott also claims that direct democracy will be able to transmit high enough information at scale to satisfyingly solve virtually all major decisions needed by a global society. Cockshott’s model’s deserve to be one of the one hundred flowers we let blossom in testing, but they are wonky and ill-suited to replace a global economy in the ways that he believes they will, most notably, because they sidestep issues of complexity, local knowledge, and revealed preference by artificially constraining the real world difficulty of these problems especially at scale. Determining the realistic limits to these and related approaches with independent outside auditors and real-world testing could help prevent us from damning ourselves with over-reliance and directing us towards much needed modernizations and pivots towards functional sustainability. His last bullet point is telling as well. His electronic payment cards would of course create a centralized super surveillance network, required for most central planning initiatives, wherein the ableist and workerist value system of an individual’s worth is their labor, replaces the grotesque capitalist notion that an individual’s worth is their wealth.

Networked Bootstrapped Experiments in Solarpunk Mutualism

M Black states, “The problem for inter-firm coordination within a market is simply that there is no mechanism which enables firms to actually coordinate their plans together and make mutual adjustments as necessary. The ideal market lacks not only a mechanism for coordination (as could exist in, e.g., a cooperative federation or a cartel) but also inhibits cooperation from the start because the competitively stable strategy within a competitive market is always non-cooperation.” as if this were a fundamental truth of markets rather than a myopic view of how they (sort of) exist now. Indeed, though regional confederations do already make complex decisions about various aspects of markets and production in large-scale co-ops and networks of co-ops, similar interventions are another space for experimentation in a hybrid economy. What does it look like for markets and direct democracies and consensual partial centralizations of coordination look like? No doubt, authors like Prytchiko and Lavoie would react in horror at the undermining of the perfect Laws of Profit, but we can work on different models that accept a degree of negative externalities of one kind (inefficient incentives) in favor of positive externalities of another kind (elimination of perverse accumulation). It seems likely that these forces would naturally compete and vie for legitimacy in the social will through proving themselves in action.

This thread from a YPG veteran discusses how Rojava is similarly gradually introducing various collectivizations, resisting or dismantling monopolies, and utilizing currencies amidst a living experiment in Social Ecology that resembles much of what mutualists have advocated for centuries only modernized for the new era. Imperfect as it is real, they are also very much attempting to put into practice more ecological and solarpunk principles while defending themselves against fascist takeover from many directions at once.

Solarpunk is the blending of high-tech, sustainable green innovation with accessibility, and traditional forms of low-tech DIY wisdom. I think it provides a vision for what a modern economic mesh of decentralized coordination could strive for. We must build from the thriving of those most vulnerable in not creating a new capitalist hell-hole of ableism and exploitation. Through this form of sensitive local knowledge, in which we build from the complex needs and preferences of individuals, while constantly seeding spaces of innovation, we can start to practice the new economy with the tools of what is in front of us. Building towards our liberation will look different than any of us can plan, because we are limited in our knowledge of not just the future, but also of each other. But using some version of a Maximum Viable Economic Planning measure we can tease out what strategies are most viable and most worth the risks of testing with our scarce resources. We can bootstrap some proofs of concept and revisit our prior MVEP measures with the new information we gained as a result. As such this measure forms the basis of a networked mesh of new economies.

The problem is inherently complex and, as Aurora notes, complexity itself is a meaningful goal when it stands in for the depth of vibrant choices available to people and societies. Utilizing every form of complexity maximizer available to us, including both mediums of exchange and large-scale decentralized social planning, we increase our chances of feeding the solarpunk future, already sprouting around us in the heart of this massive and violent collapse of the old order.

- Thanks to @hdvalence for helping me think all of this through! Here is further explanation from him: In that picture there are 8 cores in a 2×4 layout, each of which has a bunch of processing logic (the more organic-looking blobby area) and its own cache (the solar-panel looking area). Zooming in to one of the cores you can see that fully half of the area is spent on the big data cache, which is used to avoid having to communicate with the main memory. Then zooming in to the other part of the core you can see even more caching layers (the regular patterned areas, laid out in tiles) fit in with the actual processing logic (the blobby areas, laid out algorithmically). Zooming all the way out, there’s a second chip the same size as this entire unit that’s dedicated to the main memory. More on this here.

Mutual Exchange is C4SS’s goal in two senses: We favor a society rooted in peaceful, voluntary cooperation, and we seek to foster understanding through ongoing dialogue. Mutual Exchange will provide opportunities for conversation about issues that matter to C4SS’s audience.

Online symposiums will include essays by a diverse range of writers presenting and debating their views on a variety of interrelated and overlapping topics, tied together by the overarching monthly theme. C4SS is extremely interested in feedback from our readers. Suggestions and comments are enthusiastically encouraged. If you’re interested in proposing topics and/or authors for our program to pursue, or if you’re interested in participating yourself, please email editor@c4ss.org or emmibevensee@email.arizona.edu.