View or download a PDF copy of Kevin Carson’s C4SS Study: Capitalist Nursery Fables: The Tragedy of Private Property, and the Farce of Its Defense

Introduction

Since the beginning of class society, every ruling class has required a legitimizing ideology to justify inequality and to frame its own privileges as deserved. As Thomas Piketty puts it:

Every human society must justify its inequalities: unless reasons for them are found, the whole political and social edifice stands in danger of collapse. Every epoch therefore develops a range of contradictory discourses and ideologies for the purpose of legitimizing the inequality that already exists or that people believe should exist. From these discourses emerge certain economic, social, and political rules, which people then use to make sense of the ambient social structure. Out of the clash of contradictory discourses — a clash that is at once economic, social, and political — comes a dominant narrative or narratives, which bolster the existing inequality regime.1

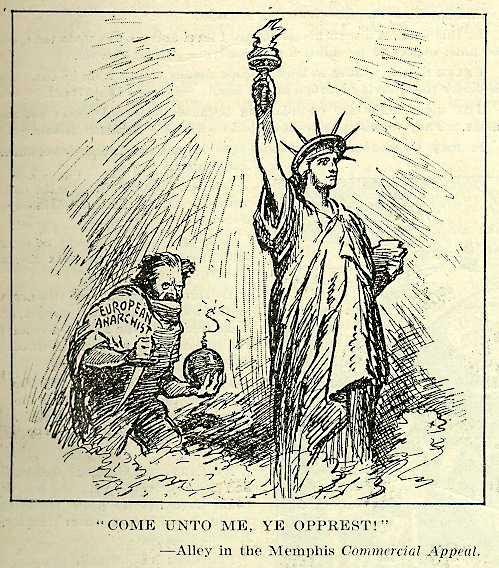

This has been true of all class societies going back to Menenius Agrippa’s parable of the body, recounted by Plutarch. Menenius was a spokesman for the patricians who had enclosed — privatized — the Roman public lands and reduced the peasantry to debt peonage. The patricians, you see, needed all that extra wealth — just as the pigs on Animal Farm needed the milk and apples — because they worked so hard serving the public good.

It once happened that all the other members of a man mutinied against the stomach, which they accused as the only idle, uncontributing part of the whole body, while the rest were put to hardships and the expense of much labour to supply and minister to its appetites. The stomach, however, merely ridiculed the silliness of the members, who appeared not to be aware that the stomach certainly does receive the general nourishment, but only to return it again, and redistribute it amongst the rest.2

But it has nowhere been more true than under modern capitalism. To quote Piketty again:

In today’s societies, these justificatory narratives comprise themes of property, entrepreneurship, and meritocracy: modern inequality is said to be just because it is the result of a freely chosen process in which everyone enjoys equal access to the market and to property and automatically benefits from the wealth accumulated by the wealthiest individuals, who are also the most enterprising, deserving, and useful.3

Classical liberalism, and the subsequent legitimizing ideologies of capitalism that emerged from it, are rife with historical mythology, robinsonades, and just-so stories that attempt to explain the emergence of the various institutional features of modern capitalism as a spontaneous emergence from a “state of nature.” In the words of Karl Widerquist and Grant McCall, capitalist philosophers and political theorists “feel free to make wild assertions about prehistory, the ‘state of nature,’ or any remote peoples without fear that anyone will ask them to back up their claims with evidence.”4

Take “the Lockean attempt to justify private property rights by telling a story of ‘original appropriation’,” as Widerquist and McCall confront it:

…[T]heir appropriation story is a fanciful tale about rugged individuals who go into “the state of nature” to clear land and bring it into cultivation. Do propertarians actually think this story is true? After thinking over their arguments I realized to some extent the answer is yes. They think at least that there is truth in it, that “private” “property rights” are somehow more natural than public or communal “territorial claims.”5

In the specific case of capitalist notions of private property, Enzo Rossi and Carlo Argenton call these myths “folk notions of private property rights.”

We use empirical evidence from history and anthropology to show that folk notions of private property — down to and including self-ownership — are statist in an unacknowledged way…. [T]he main empirical claim we rely on is usually ignored by contemporary political philosophers, but relatively uncontroversial among the relevant specialists: folk commitments to the political centrality of private property are a product of the agency of states.6

But the concept applies more broadly to folk notions of a whole variety of phenomena that characterize modern capitalism.

This paper is an attempt to debunk some of the major folk notions in capitalist ideology — including both popular polemics and scholarly literature by political economists — concerning the institutional features of capitalism. These include not only modern Western notions of “private property” in the sense of individual, fee-simple, alienable, commodity property in land, but such things as the predominance of the cash nexus, specie currency, and the wage system. In every case, the right-libertarian folk notion of a given institutional feature’s origin takes the form of a speculative “likely story” about the origin of the institution in the prehistoric past, utterly ungrounded in any historical or anthropological data, that attempts to justify it as the spontaneous product of free human action in a state of nature.

To the extent that many such just-so stories were formulated by thinkers like Locke or Smith, at a time when the body of relevant knowledge from history and anthropology was largely or mostly undeveloped, they are at least somewhat understandable. Even then as we shall see below in the case of Locke’s disregard of long-established common property rights in his own country, there was some degree of deception involved — self- or otherwise. But the fact that right-libertarian and capitalist ideologists continue to argue on their basis is considerably more difficult to excuse.

To take one example, consider the utterly ahistorical explanation of the origin of specie money as a way of addressing the problem of “double coincidence of wants,” which was uncritically regurgitated by (e.g.) Mises and his followers in the 20th century7 — a completely theoretical attempt at reconstructing the history, not only with no recourse whatsoever to any actual history, but in the face of actual evidence to the contrary.

The same is true, to a greater or lesser extent, of right-libertarian treatments of modern Western culture-bound concepts of “private property in land” as the spontaneous result of peaceful initial appropriation by individuals, the emergence of cash nexus economies as a natural result of the “propensity to truck and barter,” and the treatment of the wage system and the concentration of capital ownership as the result of hard work and thrift by “abstemious capitalists.”

In every case, the actual truth turns out to be that the phenomenon in question, far from arising spontaneously or naturally, has resulted from the massive use of force by states, acting on behalf of dominant class interests, to bring it about by forcibly suppressing the alternatives. The actual history of all these institutional features of capitalism is one, as Marx put it, in standing Smith’s stories of initial appropriation and original accumulation on their heads, “written in letters of fire and blood.”

Our modern capitalist folk-belief in private property, for example, “is largely a product of the state, due to two distinct but related historical developments.”

Crudely, the first one is the creation by the first states of an order in which individual private property is central and politically salient. The second one is the early modern state-backed rise of capitalism.8

Obscuring the role of force in establishing the structural features of capitalism is essential to the project of legitimizing it. As Rossi and Argenton argue, the framing of capitalism as something that arose by natural, non-coercive means, with no need for violations of self-ownership or the non-aggression principle, is central to its legitimacy. And in the light of actual history, capitalism fails to meet its own legitimizing criterion:

The basic libertarian argument we discuss can be summarised as follows:

- P1: Any socio-political system that emerges and reproduces itself without violations of self-ownership is legitimate.

- P2: A capitalist system can emerge and reproduce itself without violations of self-ownership.

- C: A capitalist system can be legitimate.

Note the ‘can’ in the second premise. That argument is hypothetical. Factual considerations about how capitalism came about in the actual world cannot disprove the second premise. However — and this is the crux of our argument — the actual history of capitalism and the related genealogy of our notion of self-ownership lead us to conclude that asking whether a capitalist state can emerge without violations of self-ownership cannot help settling questions of state legitimacy, because the notion of private property presupposed by that question is a product of the private property-protecting state it is supposed to legitimise (and that sort of state, in turn, is a precondition for the development of a capitalist socio-political system).

As they note, libertarian apologists for capitalism might object that this is an example of the genetic fallacy, and it is still arguably possible to theoretically justify the model of private property extant in contemporary capitalism as morally legitimate on philosophical grounds. But the question still remains: if this particular model of property rights is contingent, if it is only one of many theoretically possible alternatives, and if it did in fact appear in actual history only as a construct of state violence, “why rest arguments on common sense beliefs in moral rights to private property if those beliefs have been acquired in an epistemically suspect way?”9 That is, you could, without contradiction, justify it theoretically without regard to history, but why would you want to, aside from the fact that you hold a set of values which is itself the product of the acts of violence and robbery that resulted in the actual emergence, in the real world, of the notion you’re trying to defend? “[T]he political salience of private property rights was established by the state’s political power, and only later became part of a widely shared moral vocabulary.”10

[L]ibertarians cannot use the intuitive appeal of private property entitlements in their defence of the capitalist state, because the historical record shows that widespread belief in the central political relevance of those commitments is the causal product of the very coercive order the belief is meant to support.11

Rossi and Argenton cite the Critical Theory Principle of Bernard Williams: “If one comes to know that the sole reason one accepts some moral claim is that somebody’s power has brought it about that one accepts it, when, further, it is in their interest that one should accept it, one will have no reason to go on accepting it.”12

And the fact that so much right-libertarian scholarship and polemic does obscure the actual historical origins of modern legal property rights standards, and continues to argue for them on ahistorical grounds, suggests that — despite the theoretical availability of a “genetic fallacy” dismissal — the ideologists of capitalism see their legitimacy as in some sense dependent on a manufactured capitalist version of history.

This is entirely reasonable, given the sheer centrality of the modern capitalist model of “private property” to the common sense view of the average person as to what is “normal,” and has been normal throughout history (the depiction of the Flintstones living in stone single-family bungalows on quarter-acre lots in Bedrock is barely even a parody of the received ideology).

This study is a declaration of war. Walter Block once called Ostrom’s Governing the Commons “an evil book,” because it undermined belief in private property rights — “the last, best hope for humanity.” It is my fondest wish that he will hate this paper sufficiently to print it out and burn it.

I. Private Property

As Widerquist and McCall argue, the myth of individual private appropriation in the mists of the distant past is implicit in most of Western liberal political philosophy. But it’s most thoroughly stated by self-described “libertarians.”

The belief that at least some property rights are natural is extremely common in Western society today, but the most thorough arguments for that belief come from a school of thought whose members tend to call themselves “libertarians.” They are sometimes called or have some overlap with right-libertarians, propertarians, classical liberals, neoliberals, anarcho-capitalists, and so on. We use the term “propertarianism” for all theories involving a natural rights justification of unequal private property: the belief that natural rights, including the right to be free from interference (negative freedom), imply the necessity of a private property rights system with strong (perhaps overriding) ethical limits on any collective powers of taxation, regulation, or redistribution.13

The private appropriation myth, explicitly stated or implicitly presupposed throughout Western political philosophy, generally takes the following form:

Before any government comes into existence, an individual goes into a virgin wilderness, clears a piece of land, plants crops, and thereby appropriates full ownership of that piece of land. From that starting point, property is traded, gifted, and bequeathed in ways that lead to something very much like the current distribution of property in a market economy.

And of course it implicitly assumes that, given freedom of appropriation, appropriation will spontaneously take the form of individual ownership, fully transferable, heritable, and alienable.14 Unless explicitly provided otherwise by mutual agreement, and as a deviation from the norm — appropriation of land can only be by individuals.

The classic example of the private appropriation myth is in Chapter 5 of Locke’s Second Treatise:

The Labour of his Body, and the Work of his Hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever then he removes out of the State that Nature hath provided, and left it in, he hath mixed his Labour with, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his Property. It being by him removed from the common state Nature hath placed it in, it hath by this labour something annexed to it, that excludes the common right of other Men. For this Labour being the unquestionable Property of the Labourer, no Man but he can have a right to what that is once joined to, at least where there is enough, and as good, left in common for others.15

He goes on to argue that “the chief matter of Property” being not the fruits of the earth or livestock, but “the Earth it self” — and this was indeed the chief matter of property for Locke and the class he represented — land is legitimately removed from the common by exactly the same means. “As much Land as a Man Tills, Plants, Improves, Cultivates, and can use the Product of, so much is his Property. He by his Labour does, as it were, inclose it from the Common.”

Locke, by including “the Turfs my Servant has cut” among his list of examples,16 gives away the game. And indeed, in an exchange several years ago in which I was arguing against the legitimacy of any property title in land not founded on direct alteration by labor, a right-libertarian eagerly pressed me on the question of whether such labor appropriation could be legitimately accomplished through the work of those in one’s hire.

And among more recent political theorists who assert, or implicitly assume, the individual private appropriation hypothesis with no apparent felt need to provide evidence, Widerquist and McCall list Hayek, Epstein, Narveson, Rothbard, and Hoppe.17

These theorists assume the hypothesis mostly from a priori grounds, rather than attempting to demonstrate it with historical evidence. To the extent that they address the question of evidence at all or recognize that any is needed, they typically cite this assertion from Hayek’s Law, Legislation, and Liberty:

…the erroneous idea that property had at some late stage been ‘invented’ and that before that there had existed an early state of primitive communism … has been completely refuted by anthropological research. There can be no question now that the recognition of property preceded the rise of even the most primitive cultures …. [I]t is as well demonstrated a scientific truth as any we have attained in this field.

But in so doing they take Hayek’s bare assertion as proof, without looking into the meager handful of anthropological sources he cites or examining whether they actually bear out his claim. In fact one of the authorities he cites, A.I. Hollowell, explicitly warned against treating any property system which was not full-blown communism as individual private property in the modern sense.18 Comparing the original sources’ actual claims to the use Hayek made of them is reminiscent of the way in which Hastings, in the Permanent Settlement, managed to construe limited village headman rights as “sole, despotic dominion.”

As with the social contract, some capitalist ideologists might attempt to salvage the just-so stories of private property’s origin by claiming that it was never meant to be a literal historical hypothesis, or at least that its historical truth is not accurate for the validity of their theory. The preceding “state of nature” is, or might be, simply a theoretical construct in comparison to which we can evaluate the relative benefit of private appropriation.19

The problem with this is that we must compare the actual benefits and harms of our existing distribution of private property and rules for its governance, not just with one theoretical state of nature with no property rules, but with any number of conceivable alternative distributions and sets of rules — including those which were actually suppressed to create the existing ones.

Mainstream, or capitalist, economists argue that private property rights and market exchange are indispensable for rational economic calculation. Such arguments implicitly assume that the “private property rights” equate to the particular version of private property rights that exists under modern-day capitalism — individual, fee-simple, commodity ownership of land, and tradeable shares of equity in the firm.

But it is illegitimate, on the grounds of capitalist economists’ arguments that property rights of some sort, tradeable in a market of some kind and sold at a market-clearing price, are needed to address calculation issues and the like, to justify anything like the current property rights system in particular. The current system of property rules is entirely contingent, is the result of state force on behalf of dominant economic classes, and is only one among many theoretical alternative property rights models.

Capitalism is predicated not just on “private property rights” and markets, as such, but on a particular form of private property rights — namely individual private property.

Not only is our system of capitalist property rules entirely contingent, but upon any rational inspection it is quite suboptimal, reflecting the dominant classes’ interest in rent extraction even at the expense of rationality and efficiency. As I argued elsewhere:

Under the prevailing capitalist model, land and natural resource inputs — which are naturally scarce and costly — are artificially abundant and cheap, as a result of the propertied classes’ access to looted and enclosed land and resources. Capitalism, over the past few centuries, has mostly followed an extensive growth model based on the addition of more material inputs, rather than an intensive one based on making more efficient use of existing inputs. This is why corporate agribusiness is so inefficient in terms of output per acre, compared to small-scale intensive forms of cultivation: it treats land as a free good. So Latin American haciendas hold almost 90% of their ill-gotten land out of cultivation, while neighboring land-poor peasants must resort to working for them as wage laborers. And the U.S. government actually pays farmers to hold land out of use, so that sitting on unused arable land becomes a real estate investment with a guaranteed return.

Over the past century or so, the socialization of corporate inputs has become the primary expense of the state. The state subsidized the railroad and interstate highway networks, built the civil aviation system at taxpayer expense, gives oil and other extractive industries priority access to public lands, fights wars for oil, and uses the Navy to keep sea lanes open for oil tankers and container ships (See Carson, Organization Theory, pp. 65-70).

Capitalist industry follows a model based on subsidized waste and planned obsolescence, in order to avoid idle capacity. The very accounting models used by corporate management and econometricians treats the expenditure of resources as the creation of value.

On the other hand capitalist property rights make ideas, techniques, and innovations artificially costly, erect barriers and toll-gates against their adoption, and make cooperation artificially difficult.

Intellectual property causes gross price distortions, so that owners can charge monopoly rents for the replication of information (songs, books, articles, movies, software, etc.) whose marginal reproduction cost is zero. And in the case of copying new designs for physical goods or techniques for producing them, the majority of a product’s price often comes from embedded monopoly rents on patents rather than actual material and labor costs.

Copyrights on scientific research and patents on new inventions also impede the “shoulders of giants” effect, by which technological progress results from ideas being aggregated or combined in new ways. For example, according to Johann Soderberg (Hacking Capitalism), further refinement of the steam engine came to a near stop until James Watt’s patent expired.

Patents enable transnational corporations to control who is and is not allowed to produce. As a result, they’re able to offshore production to independent contractors in low-wage countries, retain a legal monopoly on the right to sell the product, and charge enormous markups over actual production cost.

Similar irrationalities result from the way ownership and governance rights are drawn for the business firm. Because governance authority is vested in a hierarchy of managers who (at least theoretically) represent a class of absentee shareholders, rather than in those whose efforts and distributed knowledge are actually needed for production, the firm is riddled with information and incentive problems and fundamental conflicts of interest.

For example, although most improvements in efficiency and productivity result from workers’ distributed knowledge of the work process and the human capital they’ve built up through their relationships on the job, they have a rational incentive to hoard knowledge because they know any contribution they make to productivity will be expropriated by management in the form of bonuses, and used against them in the form of speedups and downsizing. And even though workers’ knowledge of the production process is the primary source of efficiency improvements, management cannot afford to trust workers with the discretion to use that knowledge because their interests are fundamentally at odds with those of management. With information flow so grossly distorted by authoritarian hierarchy, management lives in a bubble and is forced to reduce its reliance on workers’ knowledge, simplifying the work process from above to make it more “legible” (see James Scott, Seeing Like a State) through dumbed-down Taylorist work rules. And management is forced to devote enormous resources to internal surveillance and enforcement of discipline, compared to self-managed enterprises.

Mises dismissed Oskar Lange’s market social model as “playing at capitalism,” because enterprise managers would be risking capital that they themselves did not own or stand to lose. So they would be rewarded on the upside for returns on investment without suffering personal consequences for losses.

But corporate managers under American capitalism are playing at markets every bit as much as the managers in Lange’s proposed model. Shareholders are the residual claimant of the enterprise only in theory, and even then actual legal ownership is vested in a fictional person distinct from any or all shareholders, either severally or collectively. In reality, corporate management has the same relation to the corporation’s capital (which it claims to be administering in the name of the shareholders) that the Soviet bureaucracy had over the means of production it claimed to administer in the name of the people: That is, it’s a self-perpetuating oligarchy in control of a large mass of capital which it has absolute discretion over, but did not itself contribute and does not personally stand to lose. In this environment, corporate managers’ standard approach is to hollow out long-term productive capacity and gut human capital in order to massage the short term numbers and game their own compensation, leaving the consequences to their successors after they move on….

In short, if any environment could be seen as conducive to “calculational chaos,” it’s the environment created in the capitalist economy Mises and Hayek defended. In every one of these cases, a more “socialistic” set of property rules — commons-based land and resource governance, free information, worker ownership and management of the enterprise — would result in more rationality than we have now.

In every case, property rights are assigned not only to someone other than those with the most stake in increasing efficiency, but to someone whose interests are diametrically opposed to those of actual producers and whose wealth and income derive from extracting rents from them.20

But let’s put aside the theoretical benefits of private property and get back to our primary object of inquiry: the historical accuracy of these “folk notions of private property.” Widerquist and McCall argue that Locke was not entirely to blame for his ahistorical fabrication because he “was heavily tainted with colonial prejudice and the belief in an enormous gulf between ‘civilized man’ and ‘savage man.’”21

But in fact he was negligent on three grounds. First, he made the logical error of conflating “labored on” with “individually appropriated” or “enclosed,” neglecting the real possibility — even aside from empirical reality — of land being intensively cultivated in common property regimes like the open-field system. The claim, as Widerquist and McCall summarize it, is that “labored on” land is more productive than land “left in common.” And the Lockean Proviso does not, arguably, require that enough land be left after private appropriation, for others to live on. It only requires that the increased productivity from private appropriation benefits everyone else more than enough to make up for the lack of land.22 In Locke’s own words,

he who appropriates land to himself by his labour, does not lessen, but increase the common stock of mankind: for the provisions serving to the support of humane life, produced by one acre of inclosed and cultivated land, are . . . ten times more than those, which are yeilded by an acre of Land, of an equal richnesse, lyeing wast in common. And therefor he, that incloses land, and has a greater plenty of the conveniencys of life from ten acres, than he could have from an hundred left to Nature, may truly be said to give ninety acres to Mankind. For his labour now supplys him with provisions out of ten acres, which were but the product of an hundred lying in common.23

And earlier he likewise treated “common and uncultivated” as equivalents.24 And again:

Nor is it so strange, as perhaps before consideration it may appear, that the Property of labour should be able to over-ballance the Community of Land. For ‘tis Labour indeed that puts the difference of value on every thing; and let any one consider what the difference is between an Acre of Land planted with Tobacco or Sugar, sown with Wheat or Barley, and an Acre of the same Land lying in common, without any Husbandry upon it, and he will find, that the improvement of labour makes the far greater part of the value.25

By assuming without argument that land can only be either foraged in common or cultivated as individual private property, as mutually exhaustive alternatives, Locke leaves himself open to charges of logical incoherence — or worse yet of disingenuousness.

Second, as a factual matter he ignored the factual evidence right under his own nose, not in the Aboriginal nations of America but in his own country, in most villages in England, of peasants working the soil under collective property systems. Third, he posited a theory of individual appropriation by admixture of labor which was factually incorrect and ahistorical, as could be known from events within living memory in which land — land already claimed as the common property by those working it, based on their previous and ongoing admixture of labor from time out of mind — passed from common pasture and waste and from open fields into the hands of individual enclosers.

And all of this together means, of course, that the claims that the requirements of the Proviso are met by increased productivity are nonsense. The private property of the enclosure was obtained, not at the expense of hunter-gatherers who were foraging over vast tracts of land in order to feed themselves, but at the expense of peasants who were already putting the land to agricultural use and using it to feed themselves, and were robbed of their independence. In fact, contrary to Locke’s fabricated non-zero-sum-scenario, the land was enclosed precisely in order to prevent its agricultural use by independent peasants, and to force them to work for someone else’s benefit. Locke’s entire nursery fable passes off a zero-sum relationship as mutually beneficial. Like the rest of capitalist ideology, its function is to obscure or conceal exploitation and create the illusion of common interest.

This suggests that the various statements of the folk history of private property in Western political theory reflect not so much ignorance as a deliberate ideological project. As Widerquist and McCall put it, Grotius, Pufendorf, Locke, Hume, Blackstone et al

were aware that traditional land-tenure systems had been nonexclusive throughout most of recorded European history but they sought to marginalize those forms of ownership, and over the course of centuries, they succeeded.

Many scholars argue that Locke self-consciously designed at least two of his principles to justify both colonialism and enclosure.26

Lockeanism eventually revolutionized the world’s conception of what property was by portraying full liberal ownership as if it were something natural that had always existed, even though it was only then being established by enclosure and colonialization.27

Locke’s argument that foraging only entitles the foragers to property in their actual kill, because of foraging’s alleged failure to alter or improve the land, certainly has this functional effect.

Unfortunately for foragers, no matter how long they and their ancestors foraged on a specific territory, they never gained the right to keep foraging on that land when someone wants to farm it. This principle is important not only for fulltime hunter-gatherer societies, but also… for many precolonial or pre-enclosure farming communities that were partly dependent on large foraging territories in between farms. The labor-mixing criterion gives colonial settlers and European lords the right to take most of the world’s land in ways that would interfere with the way most of the world’s people and their ancestors had been using it for millennia.28

Virtually the same argument was used by Ayn Rand to deny that Native American nations had any rights to the land that European settlers were bound to respect.

Since the Indians did not have the concept of property or property rights — they didn’t have a settled society, they had predominantly nomadic tribal “cultures” — they didn’t have rights to the land, and there was no reason for anyone to grant them rights that they had not conceived of and were not using. It’s wrong to attack a country that respects (or even tries to respect) individual rights. If you do, you’re an aggressor and are morally wrong. But if a “country” does not protect rights — if a group of tribesmen are the slaves of their tribal chief — why should you respect the “rights” that they don’t have or respect? …[Y]ou can’t claim one should respect the “rights” of Indians, when they had no concept of rights and no respect for rights…. What were they fighting for, in opposing the white man on this continent? For their wish to continue a primitive existence; for their “right” to keep part of the earth untouched — to keep everybody out so they could live like animals or cavemen. Any European who brought with him an element of civilization had the right to take over this continent, and it’s great that some of them did.29

Widerquist and McCall are apparently among those scholars who believe Locke pursued a deliberate project of justifying enclosure and settler colonization.

Locke could hardly have been unaware that his theory provided a justification for an ongoing process disappropriating European commoners and indigenous peoples alike or that that process amounted to redistribution without compensation from poor to rich. This observation raises serious doubts that the principles contemporary propertarians have inherited from him reflect some deeper commitment to nonaggression or noninterference.30

Erik Olsen suggests the theories of appropriation by Grotius, Locke, et al were not simply a hypothesis about the past, but an attempt to create modern private property and legitimize the suppression of its predecessors. “[E]arly modern original acquisition stories…sought to construct and create property in a certain way.” It was

a project of creation that is both reductive and totalizing. It is reductive in that it delimits and restricts the conceptual and discursive terrain of property in a way that privileges the classical liberal paradigm. This means in turn that it is a totalizing project that seeks to universalize this paradigm as the true form of property. In this way, the early modern project of creation not only crowds out alternative understandings and forms of property. It also subjects these alternatives to a normative order and hierarchy in which they are marginalized as departures from the ontological baseline of classical liberal property.31

Blackstone’s definition of property as a “sole and despotic dominion,” for example, functioned “more like an assertion than a thesis to be developed and supported.” It was not so much descriptive as constitutive: “…Blackstone starts by talking about the nature of property in general, and then immediately proceeds to conflate the nature of property in general with exclusive, private ownership of ‘external things’ by individuals.”

Blackstone was not simply reflecting an emerging political and legal culture which upheld the normativity of the classical liberal paradigm; he was a key participant in the creation of this culture, and this normativity. In the context of 18th-century English common law, this meant establishing the true nature of property in contradistinction to feudal understandings and practices and their residual influence in English law….

…He was… “thoroughly aware” of the fact that his idea of exclusive and despotic private dominion was at odds with the complexity of the common law regime of property in the 18th century, a regime that was still based partly on these same medieval understandings and practices.

The inescapable conclusion is that Blackstone’s reduction of property to exclusive private ownership was intellectually and theoretically quite intentional.32

Although the modern classical liberal theory of private property sought, and stressed, precedents in Roman Law, even Justinian’s Institutes recognized common and state property alongside individual private property in ways that modern theorists, seemingly deliberately, obscured.33 That this obscuration was deliberate is suggested by the lengths to which Locke went to reserve the term “property” only for individual holdings, resorting to expedients like “dominion” for all other cases.34

Locke, Blackstone, and other formulators of the classical liberal understanding of property also make their idealized version of property exclusive, thus ruling out by definition the very possibility of any notion of property that separates rights of possession or usufruct from residual or eminent social claims.35

To see that this creative or constitutive project was successful, we need look no further than the unexamined acceptance of the falsified classical liberal conception of “private property” in general folk beliefs, and in right-libertarian polemics about the “naturalness” of private property.36 We can also judge its success from the fact that, even among “non-ideological” economists, views on property have something of an “end of history” character to them, as if we were beyond even asking how property was constituted or whether that constitution was justified. As Christopher Pierson puts it:

Mainstream economics tends to arrive after the property has been initially allocated and tells us how it may then be moved around most efficiently. Or else it exhorts us to clarify property title, so that the logic of efficient exchanges can be enhanced. The demise of communism and the serial ‘crises of socialism’ have simply added to a sense that the most important questions about property have already been effectively answered.37

Roman law and political philosophy were the closest prior approximation to modern liberal ideas of private property, and from the Renaissance on the Roman law’s standards of absolute dominium and deference to existing titles were appealed to as a source of authority by modern legists. But ironically, the Roman intelligentsia were themselves engaged, every bit as much as the moderns, in a constructive or constituent project to rewrite history in the interests of the propertied classes.

As has been argued many times, property and particularly that special kind of private property represented by the idea of dominium (or ‘absolute ownership’) was crucial to the Romans, in a way that it had not been for the Greeks. But as is so often the case, the strength of Roman claims to the sanctity of private property was scarcely matched by the quality of the arguments in which the origins and the distribution of this property were founded. As we have seen, the most important sources for legitimate private property (rather than for legitimate transfers) lay in the principles of first occupancy and prescription (continuous occupation). Both principles could be found in both conventional and natural law. But little further justification was offered, beyond the prudential argument that it was important that title be clear (whoever was identified as the owner).

In practice, and as one would expect, the laws (and the justification of the laws) of property were generally written to serve the interests of those who had somehow managed to lay claim to (particularly landed) property in a time which had now conveniently become ‘immemorial’. Thus, for example, one explanation of the changing timeframe for usucapio (the idea that ownership could be generated by continuous occupation and which is found in the Roman Law from the Twelve Tables to the Code of Justinian) is that land-grabbers initially had an interest in establishing lawful title as swiftly as possible…. Once established, they had an interest in making it as difficult as possible to change the existing distribution of established property rights. This was the sequence — violent expropriation followed by claims to ‘the sanctity of property’ — that Marx famously identified with the process of primitive accumulation in Capital…. There is also plenty of evidence that private appropriation readily exceeded its lawful boundaries. In the years of the Roman Empire’s greatest success, the extent of the ager publicus (public lands) was ‘immense’. Some of this land, seized from conquered peoples, was distributed to military veterans…. The status of the ‘unallocated’ land was less clear. But, across time, there was evidence that effective ownership came to be concentrated among a few large landowners (and landlords). According to Nelson…, ‘patricians acquired hegemony over the uncultivated ager publicus [and] by the time of the Gracchan laws (the agrarian reforms of 133 and 122 bce ) these tracts of land had been in private hands for generations and had acquired the aura of private property’.

Although the agrarian reforms were largely confined to the reallocation of rights to the uncultivated terrain of the ager publicus, they excited violent hostility among propertied Roman elites. Cicero provides an excellent example. Cicero established his political credentials with his stand against the reallocation of property rights and the relief of indebtedness. According to him, the sponsors of such reforms

“are undermining the foundations of the political community; in the first place, concord, which cannot exist when money is taken away from some and bestowed upon others; and secondly, fairness, which utterly vanishes if everyone may not keep what is his. For, as I have said above, it is the proper function of a citizenship and a city to ensure for everyone a free and unworried guardianship of his possessions.”

This is a question-begging claim that the defenders of established private property have been making ever since.38

Taken overall, the Roman Law — especially as this was codified in the Corpus Iuris Civilis — gave unambiguous support to the claims of private property. The origins might be obscure but the integrity of present possession (however arrived at) was ubiquitous and seemingly unchallengeable.39

From here, we will go on to examine the historical record of private appropriation in more detail.

The History. Upon examination, the folk history of “private property,” and the factual assumptions it entails, fail to hold up in the face of evidence.

“Liberal” standards of ownership take, as a normative standard, that legitimate appropriation can necessarily be only individual, and must include full rights of transfer as a commodity.40 And this normative standard in turn depends on a number of empirical claims, implicit in the appropriation hypothesis, among which Widerquist and McCall list these two:

- Although foraging tends to precede agriculture, farmers are the first to significantly transform land. More simply, farming transforms land; foraging does not.

- The original appropriators are individuals acting as individuals establishing individual private property rights. That is, they are not groups acting as collectives or commonwealths to establish common or collective property rights; they are not individuals acting as monarchs to establish themselves as both owner and sovereign.41

Both of these claims are, factually speaking, false.

To take the first claim, Indigenous land governance is not merely passive, as the phrase “hunter-gatherer” suggests. The current ecosystem of the Amazon rainforest reflects hundreds of generations of deliberate shaping by Indigenous land management practices.

Our results suggest that, in the eastern Amazon, the subsistence basis for the development of complex societies began ~4,500 years ago with the adoption of polyculture agroforestry, combining the cultivation of multiple annual crops with the progressive enrichment of edible forest species and the exploitation of aquatic resources. This subsistence strategy intensified with the later development of Amazonian dark earths, enabling the expansion of maize cultivation to the Belterra Plateau, providing a food production system that sustained growing human populations in the eastern Amazon. Furthermore, these millennial-scale polyculture agroforestry systems have an enduring legacy on the hyperdominance of edible plants in modern forests in the eastern Amazon. 42

As for the second claim, although the myth treats individual private appropriation as a natural and spontaneous norm, the fact of the matter is that the great bulk of land appropriation throughout history was collective. Individual, fee-simple title to land has, for the most part, been imposed from above by state violence and involved the violation or nullification of preexisting collective title — the majority of cases falling only within the past five hundred years.

Enzo and Argenton divide private property into the subcategories of individual private property (PP1) and collective private property (PP2).43 And PP1, they say, did not come to predominate over PP2 by any process remotely resembling the folk notions of capitalism.

So we must begin to introduce the anthropological and historical evidence, which shows how PP1 should not be considered a politically neutral baseline…. If there is anything that emerges as such a baseline from the historical and anthropological record is a virtually unanimous understanding of property as PP2…. Bearing in mind that the process is neither linear nor synchronic, the mainstream view among anthropologist is that, as an influential review article puts it, “social evolution can be characterized heuristically as having overlapping institutional scales of organization: the family level (bands), local groups (tribes), chiefdoms, and states. […] Special forms of property can be associated with increasingly broad levels of integration.” Indeed, until about 12,000 years ago, all humans lived in hunter-gathering or foraging bands. A standard feature of band societies of this kind, and of hundreds of village and/or tribe-based societies as well, is a land tenure system based on some variation of PP2. Though moveable property tends to be held by individuals, land — the main productive resource — is held by a kinship-based collective, typically sustained by an ethos of reciprocity.44

The empirical evidence… shows how what is often taken by libertarians to be the spontaneous expression of the free individual human will — i.e. PP1-based capitalism — turns out to be something of a radically different nature. Without the state, PP1 would not be what it is.45

Now, Enzo and Argenton, in arguing for the origin of our system of private property rights in state violence, at least stipulate that some similar system of rights might hypothetically have come about, in an alternate timeline, by non-coercive means. I will go further and argue that they could not have — or at least that it would have been extremely unlikely.

If we start from the forms of collective or communal property that prevailed in Medieval Europe before the imposition of private property via enclosures, and various versions of the open-field village that existed as the universally predominant form of property from the neolithic until its “privatization” by one state or another, we see that such collective property could not have been broken up into aliquot individual holdings on a large scale without violating the existing governance rules of that collective property. In fact the imposition of modern capitalist private property directly entailed the suppression of collective property systems, with their guaranteed rights of access to the means of subsistence or their “guaranteed minimum” of basic subsistence, precisely because the latter undermined capitalism’s imperative of surplus extraction.

And if right-libertarian ideologists concede this point, they’re left in the position of arguing that capitalism, a system they regard not only as beneficial but indispensable to human progress, could only have come about through systematic violations of the very libertarian principles they promote. They are forced to treat the role of the state, of robbery, conquest, and enslavement, in the foundation of capitalism as a sort of felix culpa that brought the most moral system into existence through immorality.

To be sure, that assumption is implicit in much of classical liberal literature and classical political economy. And the agenda, if hidden, was still very real. Michael Perelman argues that “classical political economy was never willing to rely completely on the market to organize production. It called for measures to force those who engaged in self-provisioning to integrate themselves into the cash nexus.”46 “…[C]lassical political economy was concerned with promoting primitive accumulation in order to foster capitalist development, even though the logic of primitive accumulation was in direct conflict with the classical political economists’ purported adherence to the values of laissez-faire.”47 And again: “The classical political economists took a keen interest in promoting primitive accumulation as a means of fostering capitalist development, but then concealed that part of their vision in writing about economic theory.”48

I suspected that the continuing silence about the social division of labor might have something important to reveal. Following this line of investigation, I looked at what classical political economy had to say about the peasantry and self-sufficient agriculturalists. Here again, the pattern was consistent.

The classical political economists were unwilling to trust market forces to determine the social division of labor because they found the tenacity of traditional rural producers to be distasteful. Rather than contending that market forces should determine the fate of these small-scale producers, classical political economy called for state interventions of one sort or another to hobble these people’s ability to produce for their own needs.

In their unguarded moments, the intuition of the classical political economists led them to openly express important insights of which they may have been only vaguely, if at all, aware. As a result, they let the idea of the social division of labor surface from time to time even in their more theoretical works. The subject typically cropped up when they were acknowledging that the market seemed incapable of engaging the rural population fast enough to suit them — or more to the point, that people were resisting wage labor. Much of this discussion touched on what we now call primitive accumulation.49

Adam Smith, Perelman suggests, owed his greater fame and popularity compared to his predecessors to the fact that he mostly glossed over the ugly details of primitive accumulation that the latter addressed frankly. Rather than directly acknowledging the violence that was taking place right before his eyes, he resorted — much like Locke — to a “conjectural history.” Like a modern-day writer of op-eds at some billionaire-funded think tank — the Adam Smith Institute, let’s say — Smith did his best to obscure the origins of capitalism and the quite visible ongoing robberies that were necessary for its further development, and instead resorted to edifying platitudes about the invisible hand.

Smith’s reliance on conjecture and anecdote is understandable. In his revision of political economy, many facts — especially those concerning existing economic realities — would have inconveniently contradicted Smith’s intended lesson: Economic progress should be explained in terms of the increasing role of voluntary actions of mutually consenting individual producers and consumers in the marketplace.50

It’s probably not coincidental that Smith wrote at a time when political economy as a whole was shifting from the realistic acknowledgement of the need for compulsion in extracting a sufficient surplus from labor, to the belief that — dispossession having already taken place and no alternative to wage labor remaining — it might be possible to manage labor entirely through the silent compulsion of wage incentives.51 So a philosopher who swept violent dispossession and social control under the rug, and stressed natural harmonies and voluntary interaction between those who just happened to have all the property and those who just happened to have none, was well suited to the ideological needs of his time.

Although most present-day libertarians follow Smith in downplaying or deliberately covering up the necessary role of state force in the creation of the system they defend, there are some who honestly grasp this nettle. Sorin Cucerai, a classical liberal writing for the Romanian Mises Institute, frankly admits:

In the whole premodern period, one of the meanings of freedom was the absence of the obligation to have commercial relations with somebody else in order to secure your daily bread.

In short, the fundamental condition for the existence of a capitalist order is the absence of the individual autonomy in the sense of owning the source of your food. Only in this case, the commercial exchanges can become the basis of social cooperation. The importance of the food source is replaced by the revenue source, and autonomy is redefined as non-dependence on a third party in securing of a source of revenue. In this new meaning, the autonomy is guaranteed by the free exchange and the free competition and the would-be limits imposed to these two liberties are perceived as limits to the individual autonomy.

Under the modern states, the citizens are obliged to pay taxes only in denominations ( “with money”), not by products or labor. Even if one owns a food source he could not keep his property if he does not engage in commercial relations on a monetarised market in order to get the money necessary to pay the fees and taxes. The source of the revenue gets prominence over the source of food; the commercial relations are widespread because, basically, it is impossible to avoid them.

It is very important to understand that the capitalist order is not a natural order. People do not search instinctually for a source of monetary revenue. And yet, they search, in a natural way, to have access to a source of food and shelter; in other words, in their natural way, people try to become autonomous – “autonomous” in the strong sense of the word. I dare say that people seek spontaneously to own a source of food and shelter so that they do not need to make any effort to get their own food and maintain their shelter.

Capitalism is made possible only if this natural process is interrupted by an instrument that makes sure nobody could have access to food and shelter unless a monetary revenue is used as an intermediary. The survival of the capitalist order depends on this very tool. I assert all this mainly for those who promote “the anarcho-capitalism”: they consider the state to be the natural enemy of the capitalist order, it is without the state that capitalism is being supposed to flourish. Exactly the opposite is true. Without an institutional arrangement to mandate citizens to pay fees and taxes – and to do that exclusively on a monetary basis – it would be impossible to have capitalism. Without such an institutional arrangement – the modern state – the feudal order becomes more plausible than the capitalist one (because the latter could no longer subsist). From this point of view, the notion of anarcho-capitalism is a contradictory term.

Therefore, the capitalist order is not natural. Such an order can be maintained only if there is an institutional arrangement which prevents the individual from not engaging in commercial relations through the agency of money. That does not mean that the free economic exchange is unnatural. People have always practiced it. It is not the free exchange that is artificial, but the impossibility of dropping out, if you wish, of the network of commercial relations.52

But for the most part, they prefer — to borrow a phrase from Edmund Burke regarding the Convention Parliament’s preference to obscure its de facto seizure of sovereign power in determining the succession — to draw a veil of decency over the naked violence behind their “laissez-faire” system. Overwhelming, total state violence may have been necessary to create capitalism, but it is better to agree to pretend it occurred as the nursery fables describe.

Like Enzo and Argenton, Widerquist and McCall find in their own survey of anthropological literature that, in the hunter-gatherer societies that originally occupied virtually the entire portion of the earth suitable for human habitation, collective ownership of the land they foraged was the norm.53 For that matter, the whole classical liberal (and right-libertarian) trope of individuals, whether private appropriators or not, subsequently emerging into a “state of society,” whether to secure their property or not, is absolute buncombe. Human beings did not start out, as in newspaper panel cartoons, as individual nuclear family units of cavemen throwing boulders at each other from caves. Homo sapiens, before it even emerged as homo sapiens, was a species living socially in hunter-gatherer bands with a collective relationship to the natural world they occupied. (For example there is strong evidence that homo erectus, based on the existence of fossils in Oceania, constructed at least crude rafts through cooperative labor — and hence had language.)54

That is not to say there was any single, uniform model beyond the predominance of collective property of some sort. There was a great deal of variation, for instance, in the extent to which a given foraging band or clan claimed exclusive rights to a given territory to the exclusion of other groups, and on the relative porosity or definedness of boundaries between group territories. Such variation tended to reflect the relative density of population and productivity of the land.55

Although this variation entailed a spectrum ranging from nomadic home-range territories on the one end, with groups seasonally migrating between a number of sites, to densely populated and more or less settled horticultural villages on the other, the predominance of common property regimes was a common note.

Martin Bailey examined anthropological observations of more than fifty hunter-gatherer bands and autonomous villages, finding that they all had at least partially collective claims to territory. Many foragers, including famous cases like the Ju/’hoansi, have systems of collective land “ownership” in which rights to land access are guaranteed by complex systems of memberships in groups, clans, moieties, sodalities, and through networks of individual reciprocity. Richard Lee and Richard Day observe that one characteristic “common to almost all band societies (and hundreds of village-based societies as well) is a land-tenure system based on a common property regime …. These regimes were, until recently, far more common world-wide than regimes based on private property.”56

As for movable goods, while some gathered food and small game might be shared by individual families, other items like large game were shared out among the band or village. Tools, likewise, were shared among the larger group based on need.57

Indeed there is some anachronism involved in applying our word “property” at all; even a reference to communal or collective property imposes a later concept retroactively. In describing a tribe member’s or villager’s right of use and access as “property,” Murray Bookchin observes,

the terminology of western society fails us. The word property connotes an individual appropriation of goods, a personal claim to tools, land, and other resources. Conceived in this loose sense, property is fairly common in organic societies, even in groups that have a very simple, undeveloped technology. By the same token, cooperative work and the sharing of resources on a scale that could be called communistic is also fairly common. On both the productive side of economic life and the consumptive, appropriation of tools, weapons, food, and even clothing may range widely — often idiosyncratically, in western eyes — from the possessive and seemingly individualistic to the most meticulous, often ritualistic, parceling out of a harvest or a hunt among members of a community.

But primary to both of these seemingly contrasting relationships is the practice of usufruct, the freedom of individuals in a community to appropriate resources merely by virtue of the fact that they are using them. Such resources belong to the user as long as they are being used. Function, in effect, replaces our hallowed concept of possession — not merely as a loan or even “mutual aid,” but as an unconscious emphasis on use itself, on need that is free of psychological entanglements with proprietorship, work, and even reciprocity.58

The obligation to share when one had more than they could consume and others were in need resembled anthropologist Paul Radin’s “irreducible minimum” of necessaries for subsistence guaranteed by virtue of group membership: “the ‘inalienable right’ (in Radin’s words) of every individual in the community ‘to food, shelter and clothing’ irrespective of the amount of work contributed by the individual to the acquisition of the means of life.”59

And the preponderance of evidence indicates that such sharing regimes reflected the preference of a majority of their populations — including successful hunters:

Simply put, a massive amount of evidence supports the observation that “individual ownership” in band societies is far weaker than the form propertarians portray as “natural.”

A propertarian clinging to the individual appropriation hypothesis might suppose bands’ treatment of tools and big game was an early example of collectivist aggression against duly appropriated individual private property rights. Such a claim would be, at best, wishful thinking, derived not from observed events but from imagining events prior to those observed.

A closer look at the evidence disproves this wishful thinking. Nomadic hunter-gatherers have almost invariably exercised individual choice to create and to live under largely collectivist property rights structures. All band members are free to leave. They can join another band nearby; a skilled nomadic hunter-gatherer could live on their own for some time; and any like-minded group can start their own band. Six-to-ten adults are enough to start a band in most niches. In propertarian terms, these observations make virtually all obligations within bands “contractual obligations,” which propertarians consider to be fully consistent with freedom and reflective of human will.

If any group of six-to-ten adults wanted to start a community that recognized the hunter’s “natural” right to exclusive ownership of the kill, no one from their previous bands would interfere with them. Yet, although bands have been observed to split for many reasons — none have been observed to split because someone wanted to start a private property rights system. Band societies have been observed on all inhabited continents, but none practice elitists ownership institutions — even those made up of outcasts from other bands.

Therefore, we must conclude that individuals in band societies choose to establish weak-to-nonexistent private property rights.60

Widerquist and McCall argue that, by any reasonable “admixture of labor” standard, such hunter-gatherer groups had a legitimate claim to original appropriation of land as a collective.61 As we saw above, Locke went out of his way to deny the legitimacy of hunter-gatherer appropriation of land in common, based on the alleged unproductivity of their use of the land and their alleged failure to improve it. But as we also saw, this framing was factually incorrect.

In the case of agricultural communities, the folk histories of original appropriation by individuals similarly fail in the face of historical evidence. As we already saw, Locke actually equated cultivation to individual appropriation. But the historical record shows that the breaking and cultivation of land was overwhelmingly by groups, and that groups established collective property in newly cultivated land by altering it with their joint labor. “All of the thousands of village societies known to ethnographers, archeologists, and historians exercised collective control over land and recognized a common right of access to land…”

The reasonable conclusion is that the first farmers almost everywhere in the world voluntarily chose to work together to appropriate land rights that were complex, overlapping, flexible, nonspatial, and partly collective, and they chose to retain significant common rights to the land.62

As original appropriators who worked together to clear land and establish farms, swidden and fallowing communities had the right — under propertarian theory — to set up any property rights system they wanted to.63

A survey of literature on surviving autonomous agricultural villages within historical times, combined with available archeological evidence, suggests that both semi-nomadic communities practicing slash-and-burn/swidden methods and settled villages using fallowing and crop rotation, “usually have no fixed property rights in land; all members of the village are entitled to access to land, but not necessarily a particular plot.”64

James C. Scott, in Seeing Like a State, described the universal pattern in settled agricultural villages:

Let us imagine a community in which families have usufruct rights to parcels of cropland during the main growing season. Only certain crops, however, may be planted, and every seven years the usufruct land is distributed among resident families according to each family’s size and its number of able-bodied adults. After the harvest of the main-season crop, all cropland reverts to common land where any family may glean, graze their fowl and livestock, and even plant quickly maturing, dry-season crops. Rights to graze fowl and livestock on pasture-land held in common by the village is extended to all local families, but the number of animals that can be grazed is restricted according to family size, especially in dry years when forage is scarce…. Everyone has the right to gather firewood for normal family needs, and the village blacksmith and baker are given larger allotments. No commercial sale from village woodlands is permitted.

Trees that have been planted and any fruit they may bear are the property of the family who planted them, no matter where they are now growing…. Land is set aside for use or leasing out by widows with children and dependents of conscripted males.65

And while colonial authorities outside Europe, going back at least to Warren Hastings, attempted to coopt the village headman and disingenuously redefine him as a “landlord,” the headman’s authority in villages with collective land tenure is in fact largely administrative. To cite Widerquist and McCall again: “To the extent any entity can be identified as an ‘owner’ in Western legal terminology, it is the community or kin group as a whole.”66

There are individual property rights, but they inhere in the individual as a member of the group.

It is wrong to say that people living in autonomous villages have no property rights at all. The group often holds land rights against outsiders. Each family keeps the crops they produce subject to the responsibility to help people in need. Often different individuals hold different use-rights over the same land. Land rights in small-scale farming communities have been described as “ambiguous and flexible” and “overlapping and complex.”

In Honoré’s terms, the incidents of ownership are dispersed: some incidents held by various members of the community, some incidents held by the community as a whole, and some or all incidents subject to revision by the group. Throughout this book, we describe “traditional” or “customary land-tenure systems” (both in stateless societies and in many villages within state societies) variously as complex, overlapping, flexible, nonspatial, and at least partially collective with a significant commons.

Most land in most swidden and fallowing stateless farming communities is a commons in at least three senses. First, individual members of the village have access rights to cultivate a portion of the village’s farmland though not to any particular spot each year. Second, individual members usually had shared access to farmland for other uses (such as grazing) outside of the growing season. Third, individual members had access rights to forage on or make other uses of uncultivated lands or wastes….

…These societies are neither primitive communists nor Lockean individualists. Autonomous villages, bands, and many small chiefdoms around the world are simultaneously collectivist and individualist in the extremely important sense that the community recognizes all individuals are entitled to direct access to the resources they need for subsistence without having to work for someone else. Independent access to common land is far more important to them than the right to exclude others from private land.67

To the extent that communal land tenure tended to decay into a system of class stratification, or that some amount of severable individual property began to appear, it was associated with the ossification of the chief’s or headman’s authority in individual villages, or the rise of an elite stratum at the higher level of a paramount chieftaincy. “The origin of genuinely private individual landownership appears to have had nothing to do with any particular act of appropriation but rather the amassment and disbursement of centralized political power for the benefit of chiefs and other elites.”68 In other words, the earliest appearances of private property were the result of what could most accurately be described as proto-state formations.

If homesteading or appropriation by labor mean anything at all, the arable land employed in field agriculture in most parts of the world was the collective property of a village because the ground was initially broken and cultivated by the joint labor of people who saw themselves as members of an organic social body. The village commune and common ownership of arable land was near universal, according to Pyotr Kropotkin:

It is now known, and scarcely contested, that the village community was not a specific feature of the Slavonians, nor even the ancient Teutons. It prevailed in England during both the Saxon and Norman times, and partially survived till the last century; it was at the bottom of the social organization of old Scotland, old Ireland, and old Wales. In France, the communal possession and the communal allotment of arable land by the village folkmote persisted from the first centuries of our era till the times of Turgot, who found the folkmotes “too noisy” and therefore abolished them. It survived Roman rule in Italy, and revived after the fall of the Roman Empire. It was the rule with the Scandinavians, the Slavonians, the Finns (in the pittaya, as also, probably, the kihla-kunta), the Coures, and the Lives. The village community in India — past and present, Aryan and non-Aryan — is well known through the epoch-making works of Sir Henry Maine; and Elphinstone has described it among the Afghans. We also find it in the Mongolian oulous, the Kabyle thaddart, the Javanese dessa, the Malayan kota or tofa, and under a variety of names in Abyssinia, the Soudan, in the interior of Africa, with natives of both Americas, with all the small and large tribes of the Pacific archipelagos. In short, we do not know one single human race or one single nation which has not had its period of village communities…. It is anterior to serfdom, and even servile submission was powerless to break it. It was a universal phase of evolution, a natural outcome of the clan organization, with all those systems, at least, which have played, or play still, some part in history.69

Henry Sumner Maine pointed to India as the foremost surviving example of the village commune model common to the Indo-European family:

The Village Community of India is at once an organised patriarchal society and an assemblage of co-proprietors. The personal relations to each other of the men who compose it are indistinguishably confounded with their proprietary rights, and to the attempts of English functionaries to separate the two may be assigned some of the most formidable miscarriages of Anglo-Indian administration. The Village Community is known to be of immense antiquity. In whatever direction research has been pushed into Indian history, general or local, it has always found the Community in existence at the farthest point of its progress…. Conquests and revolutions seem to have swept over it without disturbing or displacing it, and the most beneficent systems of government in India have always been those which have recognised it as the basis of administration.70

Villages founded in historic times were likewise appropriated through collective labor, as recounted by Kropotkin in the case of Dark Age Europe. The village commune commonly had its origins in a group of settlers who saw themselves as members of the same clan and sharing a common ancestry, who broke the land for a new agricultural settlement by their common efforts. It was not, as the modern town, a group of atomized individuals who simply happened to live in the same geographic area and had to negotiate the organization of basic public services and utilities in some manner or other. It was an organic social unit of people who saw themselves, in some sense, as related. It was a settlement by “a union between families considered as of common descent and owning a certain territory in common.” In fact, in the transition from the clan to the village community, the nucleus of a newly founded village commune was frequently a single joint household or extended family compound, sharing its hearth and livestock in common.71

In the case of Dark Age European villages founded by Germanic tribes, we can get a picture of how common ownership evolved during the transition from a semi-nomadic lifestyle to permanent settlement, and how the open-field system developed from tribal precedents, by comparing accounts of their farming practices over time. As Tacitus recounted of the Teutons, at a time when they were still semi-nomadic, their practice was the interstripping of family allotments within a single open field. There was no rotation of crops or fallow period; the tribe simply moved on when the ground lost fertility. As the tribes became more sedentary, they introduced a simple two-field system with alternating periods of lying fallow, which gradually evolved into multiple fields with full-blown crop rotation.72

Maine cited the Indian village, in particular, as an example of founding by a combination of families. “[T]he simplest form of an Indian Village Community… [is]a body of kindred holding a domain in common…”73 And he affirms Kropotkin’s observation that even in cases where the founders of a village did not share a common origin, it created a myth of “common parentage.”74

Even after the founding clan split apart into separate patriarchal family households and recognized the private accumulation and hereditary transmission of wealth,

wealth was conceived exclusively in the shape of movable property, including cattle, implements, arms, and the dwelling-house…. As to private property in land, the village community did not, and could not, recognize anything of the kind, and, as a rule, it does not recognize it now…. The clearing of the woods and the breaking of the prairies being mostly done by the communities or, at least, by the joint work of several families — always with the consent of the community — the cleared plots were held by each family for a term of four, twelve, or twenty years, after which term they were treated as parts of the arable land held in common.75

Even in cases where a village was founded by separate families who came together for the purpose, they typically broke the ground and cultivated it through joint labor as an act of collective homesteading, and frequently developed a new mythology of a common ancestor.76

The communal model of land ownership, dating as the universal norm from the Neolithic Revolution, persisted in agricultural villages in many parts of the world until fairly recent times (among them the English open-field villages and the Russian Mir), or to some extent even the present day in some areas of the Global South.

In some variations of the village commune, e.g. in India and in many of the Germanic tribes, Maine argued, there was a theoretical right for an individual to sever his aliquot share of the common land from the rest and own it individually. But this was almost never done, Maine said, because it was highly impractical.

For one thing, the severance of one’s patrimony in the common land from the commune was viewed as akin to divorcing oneself from an organized community and setting up the nucleus of a new community alongside (or within) it, and required some rather involved ceremonial for its legal conclusion. And the individual peasant’s subsequent relations with the community, consequently, would take on the complexity and delicacy of relations between two organized societies.77 So many functions of the agricultural year, like plowing and harvest, were organized in part or in whole collectively, that the transaction costs entailed in organizing cooperative efforts between seceded individuals and the rest of the commune would have been well-nigh prohibitive.

Although less polemical in tone than Kropotkin, archeologist Bruce Trigger much more recently (2003) largely seconded the general lines of his analysis. He divides the landed property of early civilizations into three categories: collective, institutional (the domain of palace, temple, or individual political or religious personnel ex officio), and private (i.e. individual and saleable).78 Agricultural land in most ancient civilizations was predominantly collective and not bought or sold, but gradually shifted to institutional or private ownership in increasing amounts either through top-down state action or — with the introduction of money — alienated for debt. In some cases, for example Egypt, it is difficult to determine whether genuinely private land ownership — as opposed to grants of revenue from institutional estates to royal favorites or to individuals in their official capacity — existed at all.79