Welcome to the second edition of the Against Utopia monthly newsletter, where I explore problems of social organization, philosophy, biology, politics, and more through an epistemological anarchist lens. Or in simpler (cruder) terms, analyzing the authorities’ basis of knowledge and mostly concluding that they should fuck off, so we can flex our autonomy.

If you’re returning from last month, hello and thanks! If you’re new, nice to have you! Share this newsletter and tell your friends to sign up here.

This week I want to have a quick word about “domestication” of humans by the state, the resistance of autonomous hill peoples, valley “civilizations”, and an interesting biological connection between them that can tell us quite a bit about how energy metabolism organizes social possibilities.

Upland Peoples and Their Strategies for Avoiding Lowland States

In The Art of Not Being Governed [3] by anthropologist and political scientist James C. Scott, he introduces the concept of “Zomia”[1], a term coined by historian Willem van Schendel to describe the upland region of Southeast Asia and southern China. This land mass encompasses the highlands of north Indochina (north Vietnam and all of Laos), Thailand, the Shan Hills of northern Myanmar, and the mountains of Southwest China. Some experts extend the region as far west as Tibet, Northeast India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, for sociological reasons that will become clear shortly.

These areas share some common features: they are elevated and arid, and have been the home of ethnic minorities who have fought against state intrusion to preserve their cultures and way of life, and in some cases like Afghanistan, have fought multi-generational wars to maintain their autonomy from the state.

The groups of people who reside in this region have made resistance a way of life. They’ve formally derived and practiced the primary forms of state evasion, and Scott makes these forms of autonomous social organization the focus of his work. In order to understand their resistance, let’s take a closer look at what the state is, what it’s trying to do, how it uses language, and the comparative anthropology of the folks escaping its wrath.

The state apparatus in these regions sounds violent and spooky, possibly corrupt, yet it is exactly what you are thinking it is when you hear “the state”: “the government”, “bureaucracy”, “MPs”, “Congress” etc. These are no spooks, they’re not some kind of “bad” version of government that would somehow be better if it was done right, they just are the government, and Scott’s case is built upon realizing that what these upland states are doing is a form of internal colonialism, that ALL states, including Western ones, are primarily tasked with. In Scott’s take, they are a primarily extractive entity.

Like all extractive state entities, they are concerned with who their people are, how many children they have, how to count them all accurately, how to tally their production, and how to bring them to heel, so that they can extract resources in the form of taxes and people for military or civil service.

One of the key factors driving this state formation, which later enabled the state to extract taxes and grow, is the development of observable economic activity. Scott spends a considerable amount of time talking about grain cultivation practices in rice paddies in the entire region, and how rice paddy development coincides with valley civilizations, because that’s where rice grows: semiaquatic tracts of arable land in wet valleys interspersed between the more arid hills and highlands. “Observable economic activity” very literally means the ability to observe with one’s own eyes what is being grown and what is eventually produced from plots, so it can be appropriated for state use.

Scott wrote an entire other book [2] about how and why specific lowland crops the world over seem to be the same ones that produce state-level entities, but it’s worth it to divert for a bit and dig deeper into this. In his opinion, it’s not a coincidence that the same handful of crops form the base of agricultural activity that drives state formation the world over – rice, barley, millet, and wheat. There’s a very simple reason for this: all of these crops are lowland crops that grow easily, and most importantly, observably. All of them can be counted, quantified, and taxed easily by a bureaucrat traveling far outside of a state center.

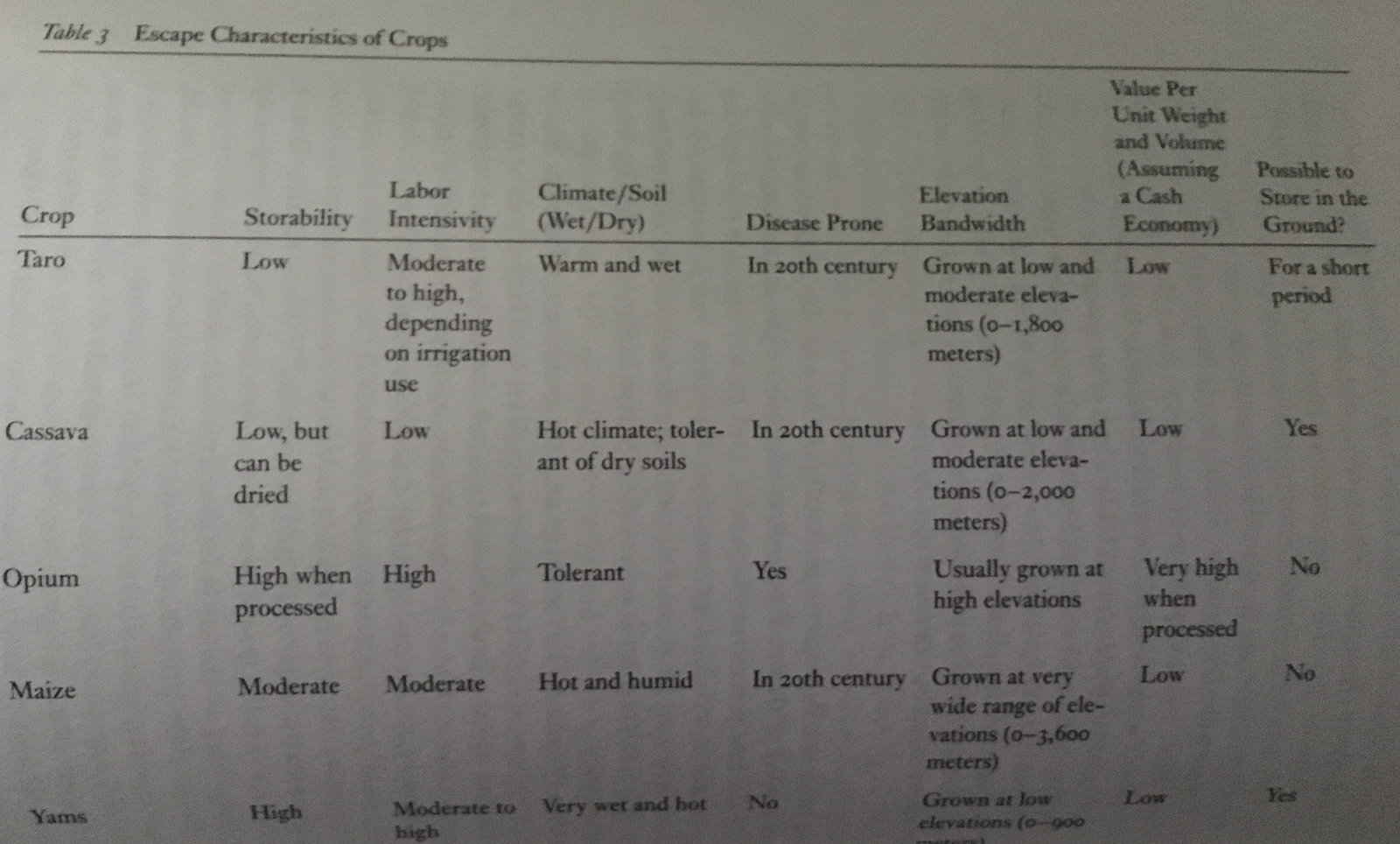

On the opposite end of this, if you’re looking to evade state control, you’re looking for crops that stagger their maturity patterns, grow fast, can grow below ground, are of little value per weight or per volume, have higher caloric yields per unit labor and per unit land, and ideally, are adapted to growth in slash-and-burn or swidden agriculture (more below on this term).

Oats, taro, yams, sago palm, cassava – mostly roots and tubers – fit the bill. Yams are suited to dry hillsides, grow wild in the mountains, and are less susceptible to attack from insects and fungi compared to rice. Taro has much of the same advantages but requires wetter soils to grow. With these advantages, these foods were referred to as “famine” foods in certain valley civilization lexicons like e.g. the Vietnamese state, because when famines hit and crops that were appropriated for state use became scant, even the lowlanders would resort to growing them to support themselves. The basis of a diet and lifestyle that gave one people their autonomy from the state, was to the subjects of the state, resilience for famines.

These two groups were not necessarily static. There’s evidence of dynamic adjustments to situational context, with groups adopting fluid ethnic identities, and fluid food development strategies seasonally as early as the 1700s if not earlier. In Laos under French rule, whole villages would move when their colonial responsibilities became too much to bear, e.g. living near a road that they were expected to maintain with corvée labor. Movement uphill was associated with swidden agriculture, as the Laotian peasantry knew that these activities were illegible to bureaucrats.

In New Guinea highland maroon communities under Dutch rule, the sweet potato paired with pig husbandry gave maroons (escaped slaves) the autonomy to get very high caloric yields per unit labor and meet all of their needs with a crop that outperformed all other crops at high altitude. It’s utility as a method of escape is best exemplified by the Spanish colonizers of the Philippines, who remarked:

[They move] from one place to another on the least occasion for there is nothing to stop them since their houses, which are what would cause them concern, they make any place with a bundle of hay; they pass from one place to another with their crops of yames and camotes [sweet potato] off of which they live without much trouble, pulling them up by the roots, since they can stick them in wherever they wish to take root.

Fig 1. Summary of escape characteristics of crops in the hill people repertoire. Crops that have higher-end elevation bandwidth in particular allow for ranging to higher elevations to escape state control (credit: James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed).

Fig 1. Summary of escape characteristics of crops in the hill people repertoire. Crops that have higher-end elevation bandwidth in particular allow for ranging to higher elevations to escape state control (credit: James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed).

The common pattern amongst all of these crops is that they 1) thrived at high altitude with little tending and 2) were not grains, and were in many ways nutritionally superior to grains. I won’t go into this too deeply, but it is a well-studied phenomenon particularly in the last 20 years that hill people, foragers, and hunter-gatherers were more robust physically than their valley agriculturalist counterparts. Their wide-ranging diets were more nutritionally complete than their agricultural counterparts, and as we will see below, agriculture’s ascendance coincided with a shrinking of the brain cavity and overall height in humans. The diet and lifestyles that statecraft selects for have a LOT to do with this.

Now, as these agricultural modes of state food production developed, alongside them grew a rich set of bureaucratic techniques, roles, and modes of social control, with new vocabularies beyond mere famine foods. The indigenous Yao people of southwestern China and Vietnam exemplify this. The term Yao originally was used to designate anyone who was obligated to perform corvée labor, which is unpaid labor for a feudal lord. As social forms continued to evolve, and feudalism receded with the ascendance of the administrative state, Yao became an ethnonym referring to anyone in the southwest and southern highlands who was essentially an unpaid laborer.

The Yao in particular are interesting – to this day, the Yao who are closer to the state, in the lowlands of southern China, have altered their social production forms to include rice paddy development and cultivation. The Yao who are closer to the highlands still practice hunting and foraging with a much smaller percent of their calories coming from rice. They also practice what Scott refers to as an “enemy of the state” – slash-and-burn agriculture or swidden agriculture.

Why is swidden agriculture so derided by bureaucrats? It’s pretty simple. Swidden agriculture allows many degrees of freedom that enable state evasion. For example, if you rewild areas of your land by planting 2-3 years in a row in the same plot, then let it all grow back and burn a new tract of land, it is extremely hard for a civil servant to determine what your production is on that one plot of land. Now consider that many of theseYao clans could number in the 50s to ~500s, and there is simply no “fair” way to begin to tax people based on an observable, justifiable metric of what they produced. You have to resort to violence and risk flight or revolt, or collect no taxes. We all know what states choose to do in this situation.

From the perspective of the administrative state, these upland people seem unruly, hard to control, difficult to find, and just plain rebellious. They have the energy and will to live hardy lives, and plan ahead by planting and hiding taro in unpredictable patterns 2-3 years at a time. They have the flexibility to grow lowland crops for trade, including things like opium. Anything and everything they could do maintain autonomy over their social organization.

What appears as backward agricultural practices in the state’s perspective is actually a volitional, political choice used as a tool in the fight against the loss of autonomy.

“Anarchist” Nutrition and Metabolism

Let’s switch gears a bit now and examine some other common features of hill peoples evading state control – nutrition and the benefits of living at high altitude.

Recall that these escape crops offered people the ability to evade state control by being simple to grow at high altitude, easy to hide, and also, by being nutritionally complete. A grain-based lowland diet holds numerous pitfalls if not properly supplemented. Diseases like pellagra, Ricketts’, scurvy, and beriberi were probably not common until a state came along and forced its people to live on subsistence diets of corn, soy, or rice, which lacked complete proteins, vitamin C, and the B vitamins.

On the other hand, all of the foods listed in the tables above and specified in individual cases have very high amounts of vitamin A, vitamin E, vitamin C, B vitamins, fibers, calcium, magnesium, potassium, and a decent amount of protein and fats. Even more importantly, they don’t come with the baggage of complex food processing methods required to make them nutritionally complete or at least not poisonous and destructive. Here I’m thinking of e.g. the nixtamalization process required to prevent pellagra from corn consumption, or the B vitamin deficiencies caused by consuming a wheat-only diet which led to the fortification of grains in the 20th century by the US government (which has its own heinous consequences [4], but let’s focus).

All of these vitamins, minerals, and nutrients contribute to healthy oxidative metabolism and general physiological robustness. The B vitamin complexes are required for functional oxidative metabolism in the mitochondrion of every cell in your body. Without thiamine (B1) for instance, electrons cannot be transported for efficient oxidative phosphorylation inside of the mitochondria, and this is responsible for many of the cognitive deficits seen in childhood malnutrition. It’s very literally the inability to provide energy to brain mitochondria in a scalable way causing an observable mental deficit.

I’m over-indexing on oxidative phosphorylation here for a reason. Many of the maladies of civilization such as diabetes, cancer, heart disease, Alzheimer’s [5], are now understood to have a mitochondrial etiology[6], or in other words, they seem to be diseases of mitochondrial energy metabolism which exact systemic consequences on the rest of the body as your physiology struggles to adapt to increasing demands without optimal metabolism. This only gets compounded by the mental stresses of modern life[7], which have been shown to have an almost equivalent effect on our biology as other types of physiological stress. In simpler terms, feeling psychologically stressed, like being stuck in traffic and not being able to escape, is almost identical to lacking the physical energy needed to meet a demand, like running away from an animal trying to eat you.

So what does mitochondrial biology, modernization, and psychological stress have to do with hill peoples and living in the highlands?

It turns out that in almost all highland peoples who maintain a form of life and social organization that approximates communal or pre-modern forms, chronic disease of the sorts described above is close to nonexistent. This connection also doesn’t disappear when one controls for infant mortality, epidemics, war, famine, and other commonly trumpeted reasons for the connection.

Robert Sapolsky cites research from anthropology, genomics, and paleontological physiology[8] showing that the ascendance of agricultural forms of social organization coincides with a near 30% reduction in lifespan, as well as far poorer bone and dental health in the fossil record[9].

In the modern era in Victorian England of 1883, the nutritional standards put in place by the state exacted such a toll that the infantry were forced to lower their height requirements from 5 ft 6 inches to 5 ft 3 inches – for men [24]!

We didn’t even touch on the fact that highlanders live comparatively slower lives[10], working as little as 2 hours per day to secure resources, avoiding commutes, engaging with loved ones more often, and avoiding the dominating psychological stresses of modern life which as we mentioned before have been shown to exact very real physiological tolls on the body.

Carbon Dioxide, Mitochondria, and the Secret to Upland Resistance

All of that being said, what’s left? Well, there’s a hidden feature of the life of hill peoples that is now being revived and actively researched after a long dormant period, that I think plays a huge role in giving them the ability and energy to resist, and ability to strive for better possibilities. This thing also contributes mightily to mitochondrial biogenesis and stability, and is one of the key diagnostic indicators of most chronic disease. That hidden thing is something swimming in the air all around us – carbon dioxide.

In 1977 in New Mexico, a study was conducted [11] on people residing at high altitude.. This study compared age-adjusted mortality rates for heart disease for white men and women living in Santa Fe from 1957-1970, in 1000 ft increments. For years before the study, it was believed that living at high altitude placed stress on our biology, as we struggled to adapt to a lower oxygen pressure.

What they found was the exact opposite.

The altitude groups 1-5 were arranged to start with the lowest altitude as group 1, with each subsequent group being 1000ft higher than the previous group, e.g. group 5 is 5000 ft higher than group 1. The death rates were normalized to the 1st altitude group, and it was found that there was a near linear relationship in the male death rate, with an effect size of 28% reduction in group 5.

This was an epidemiological study that was well controlled for race, migration, pre-existing disease, so the authors were able to eliminate a considerable amount of factors in explaining the association, but some factors remained. They comment in an apocryphal manner: “Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism of this association, if it is confirmed in other data.” It turns out that the association has been confirmed in myriad other data, but no one has as of yet elucidated a mechanism, at least officially in the literature. I will speculate about what the mechanism is at the end, but let’s take a closer look at a few more instances of this effect.

Seeking alternative explanations, some investigators expected a strong positive correlation between altitude and cancer mortality, particularly because the cosmic ray radiation at altitude could be much stronger than at sea level and was strong enough to be ionizing. Research over the decades preceding the study had shown ionizing radiation to be carcinogenic (usually nuclear bomb tests, etc).

Picking up on this, one of the other interesting studies [12] in this area sought to understand the connection between altitude, radiation exposure, and mortality specifically in heart disease and cancer. The authors began by commenting that several studies conducted in the US expected to find correlations between mortality rates for cancer and ionizing background (cosmic ray) radiation. The correlations were actually the inverse of what was expected, so this group fit models that incorporated altitude inputs as well as background radiation for predictors of mortality in order to elucidate what was going on.

The group found that negative correlations with cosmic rays and mortality from cancer and heart disease disappeared once the models included variations in altitude. Not only that, in the case of breast, intestine, and lung cancer, the correlations became positive!

On the other side of it, the correlations with altitude persisted when the model was modified to include adjustments for radiation. The altitude correlation had a significant and powerful effect in this (admittedly) observational data. The study authors concluded that one can’t neglect the negative mortality effects of radiation from this study, but that perhaps the reduced oxygen pressure of inspired air at high altitude is protective against certain causes of death.

In a 2009 retrospective cohort study of patients initiating dialysis in the US between 1995 and 2004 [13], it was observed that patients at higher altitude receive lower erythropoietin doses, yet achieved higher hemoglobin concentrations in serum. The authors expected the reverse, and along the way, also discovered yet again that in their data, patients at higher altitude also had lower mortality. Since it was 2009 and we had more powerful analytical methodologies at our disposal, the study authors had more room to speculate about the physiological effects responsible for the observed mortality increase.

By the time they wrote their conclusion, they were able to pull in recent findings from the study of cancer in hypoxia-induced factors. First, hypoxia-induced factors regulate enzymes that affect cardiovascular risk, such as VEG-F, heme oxygenase-1, i-NOS, and cyclooxygenase 2. The preceding enzymes are involved in inflammation, blood vessel growth and repair, and dilation / constriction. Enzymatic effects stemming from them and the subsequent effects on mortality had already been well established in studies at sea level. The connection the authors made here is that the benefits to mortality observed in this population most likely stem from the relative lack of oxygen, and possibly the addition of carbon dioxide replacing it.

This pattern was highly repeatable and conserved over time.

In one study [14] of 300 autopsies carried out at 14,000 feet in Peru, not a single case of death by heart attack, nor even moderate coronary artery disease was found.

Shepherds serum at high altitude has been found to exhibit profound anti-thrombotic effects [15] from life at high altitudes. Their vascular walls are also stronger and feature less clot activity. This could partly explain why they are so resilient to heart disease, stroke, and hypertension.

At a meeting of the World Health Organization in 1968 [16], it was reported that native populations in Chile and the Himalayas also had significantly less heart disease and cancer than populations at sea level.

Carbon dioxide has also been shown to inhibit in vivo generation of reactive oxygen species [17]. Essentially this is broad evidence for an overall systemic protective effect.

And so on.

But what of carbon dioxide? It seems a little out of place here. What does carbon dioxide have to do with mortality reduction? Isn’t it just waste, a byproduct of respiration?

Not really.

Besides the large effects observed in heart disease, altitude seems to have a large effect on cancers of all types, and it’s important to understand why that is.

Cancer, Carbon Dioxide, Lactate, and Acidity

Otto Warburg [18] received the Nobel Prize for discovering cellular respiration in developing sea urchin eggs. More importantly, towards the end of his career he discovered that cancer cells preferentially turn sugar into lactate, even in the presence of oxygen, a feature he called aerobic glycolysis. If you haven’t taken biochemistry, let me translate that for you.

When you sprint and your legs and lungs start to burn, the subjective experience and the measured physiological effects are typically attributed to the buildup of lactate. As you breathe harder and harder and pump your legs faster and faster, you build up this waste product, lactate, as you burn oxygen and sugar. Normally 95% of your energy is produced by oxidative phosphorylation, which produces ATP and carbon dioxide, but when there is not enough oxygen to burn your energetic substrates completely, your body switches to a form of energy production called glycolysis, which is the use of sugar to produce pyruvate and downstream of that, lactate.

Many, many cancers have the feature of over-producing lactate. Lactate has been shown to power angiogenesis, for example, which is the way that cancers begin to spread their tendrils and grow vascularity in order to get more oxygen, sugar, and fat supplied for their growth. Warburg’s great contribution was to show that even when you are sitting at rest, if you have a cancerous tumor, your body is basically panting. It’s stuck in glycolysis. It’s constantly turning sugar into lactate instead of carbon dioxide, even when there is plenty of oxygen around.

Now zooming back out, when you are at altitude, it might seem like you should be panting all the time, and that you would experience aerobic glycolysis [19], because there is less oxygen around. Based on everything I just said, you might predict that when we go to high altitudes, because we get tired faster and have less work capacity, that we’re producing more lactate, and that we might expect higher cancer rates. That would be true except for the implications of two key biophysical effects: the Haldane effect and the Bohr effect (which circumscribe the lactate paradox), which I think is what hill people above are inadvertently benefiting from.

The Haldane effect is relatively simple. John Scott Haldane discovered that in hemoglobin, the protein that carries oxygen and carbon dioxide in our blood, oxygen displaces carbon dioxide in proportion to its partial pressure in the environment. As you go higher and higher up in altitude, less carbon dioxide is displaced from hemoglobin, and cells throughout the body retain more of their carbon dioxide and bind less oxygen.

The Bohr effect is even simpler still – it was first observed by Christian Bohr in 1904, and is the ability of carbon dioxide to displace oxygen in hemoglobin as pH decreases. Surprise, surprise, as you go up in altitude, carbon dioxide works to form carbonic acid in the blood more easily, and the resultant decrease in pH (increased acidity) makes it harder to bind oxygen in the blood.

The downstream effect of this is that there is less oxygen in the mitochondria of the cells, and the oxygen is more efficiently consumed by oxidative phosphorylation, an energetic pathway that “competes” with glycolysis. I say competes in quotes because oxidative phosphorylation is dependent on the first part of the glycolysis pathway in order for the overall pathway to function, so competing is a bit of a misnomer. This is a detail that’s ancillary to the broader effect which basically demonstrates that if you are in an oxygen-scarce environment, more efficient use of oxygen results in far less lactate production and the reduction of aerobic glycolysis, the main feature of cancer energy production.

Whew, I know that was a mouthful of big words, but we’re almost done.

Mitochondria: The Powerhouses of Social Organization?

Now what evidence is there for this? Well, if we expect that there is less oxygen present at altitude, and this leads to increased absorption and efficiency of oxygen consumption, we’d expect the organism to also make more mitochondria to meet the demands of lack of oxygen. Either that, or we’d expect efficiency gains within the mitochondria themselves. And we’d expect less lactate production at altitude.

It turns out that all are true.

In an old study comparing cows raised at sea level and cows acclimated to very high altitudes [20], the high altitude cow had direct mitochondrial counts 40% higher than the sea level cows, evidence of massive amounts of mitochondrial biogenesis to acclimate to altitude.

Additionally, in a different study examining rat heart, liver, and kidney mitochondria [21], ND6, COX, and other genes involved in energy production within the mitochondrion all were 30-40% higher in rats acclimated to high altitude vs. sea-level rats. Ninety-five percent of all energy production in the rat (and us) occurs via oxidative phosphorylation which takes oxygen and sugar and turns it into carbon dioxide and energy. At these higher altitudes, it appears that the genes used specifically to upregulate oxidative phosphorylation and consequently produce more carbon dioxide were massively upregulated. Energy production became so efficient that the rats produced very little lactic acid / lactate.

Alan C. Burton, a founding father of biophysics, late in his career noticed this correlation between altitude and significantly reduced cancer rates[22]. He hypothesized that there is a connection between intracellular pH (not serum pH, which is buffered and strictly controlled by the body to a narrow range) and carcinogenesis. On its face, it seems like a reasonable assumption particularly if we take Warburg’s aerobic glycolysis into consideration.

Lactate produced downstream of aerobic glycolysis has a pKa of 3.82, which means above a pH of 3.82 it is lactate, and below it is lactic acid. We’re talking about finely tuned microenvironments here when we talk about the acidity of a cell. A cell’s momentary (over)production of lactate can easily produce pHs below 3.82 but that’s just a bit of speculation. The point is that at altitude, the increase in carbon dioxide creates momentary decreases in alkali reserve because the increased carbon dioxide creates carbonic acid through the buffer system in the blood. This results in a slightly reduced but still well-buffered pH at altitude, and as we saw before, a marked reduction in lactate.

Burton had speculated that if this is what happens at altitude, it might be possible to simulate this effect with a drug, acetazolamide, which blocks the enzyme responsible for the buffering of carbon dioxide in the blood. At the time of his writing, acetazolamide had been given to cancer patients and tumor reduction had been observed, but no one followed up to see if this was explicitly due to acetazolamide or some other factor. All we do know is that lactate production was observed to be lower in hill populations, and that this effect could be mimicked by a drug.

To date there has been only one study that I know of that demonstrates a full picture of increased carbon dioxide retention at altitude leading to biogenesis of mitochondria with increased efficiency with an observed effect of improving some disease state, and that is FZ Meerson’s work, as cited by Ray Peat[23]. Meerson was able to demonstrate that rats at altitude increased overall count of mitochondria per unit brain mass, with more efficient use of oxygen as a percent concentration of oxidative enzymes, leading to prosociality and increased learning ability.

Increased prosociality and learning ability as a result of mitochondrial energy production and efficiency.

Recently, the titan of mitochondrial genetics, Douglas C. Wallace, showed that in mice under acute psychological stress, mitochondrial functions modulated the neuroendocrine, metabolic, inflammatory, and transcriptional responses[7]. This study is broadly instructive and ties everything in the picture we’ve painted together, in my opinion.

Wallace’s group, in a very well-controlled study, was able to show that when you put mice in a restraint stress condition, which is putting them into a situation where they are enclosed and can’t escape, kind of like mouse prison, the explicit, minute functions of the mitochondria organize the overall physiological response and the ability to respond to stress at every level of organization. Let me restate that: when a mouse is under solitary confinement, Wallace’s group found that mitochondrial energy production quality facilitates the ability of its cells, organs, organ systems, and cognitive functions to respond to that stress. This takes shape in a few different forms in the data.

The mice in the study were modified in specific parts of their genomes to make mutant mice that would be bad at transporting the proteins necessary for energy production from the cell nucleus to the mitochondria. Other variants would specifically have defects in the electron transport chain, where electrons are transported from sugars and proteins in the mitochondria, terminating in oxygen to make carbon dioxide, and so on. Then, the researchers picked neurotransmitters, hormones, and other biomarkers that are indicative of the functioning of systems responsible for responding to stress in the mice. The systems in question in this study were the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary axis, and the study authors were interested in the levels of norepinephrine, epinephrine, serotonin, adrenaline, and other compounds generated as a result of the activity of these systems when the mice were placed in restraint stress.

What they found was that the mice with very specific defects of mitochondrial energy production experienced profound deleterious effects from the level of the cell all the way through to the entire organism. Their organs, their axes, and the entire mouse failed to adapt to the insult of restraint stress if the right defect in energy production was introduced. Some were more deleterious than others, but the overall point stands: if you can’t produce energy under stress, whether it’s psychological or physical materialist in its nature, you fail to adapt down to the level of your lived biology.

In my speculations, though this hasn’t been shown to be the case in humans yet, there is no reason to suspect that our own responses to psychological stress aren’t mitigated in the same or similar ways, and modern life in bureaucratic, systematic civilizations is one long constant stressor of domination that strips people of their autonomy. I think on a near societal scale we are experiencing learned helplessness from chronic psychological stress, and the people who have successfully evaded state control to self-determine their circumstances not only have a desire to do so, they also have real, material, physiological advantages, if the story I’ve woven together makes sense.

Conclusions

We’ve seen how hill peoples who are escaping (and continue to resist) early attempts at statecraft in valley regions used “escape crops” for self-determination of their way of life. This strategy coincides with the crops being nutritionally complete, and the interesting biological effect that rode along with these desires for freedom – residing at high altitude conferred benefits against cancer, heart disease, and other chronic illnesses, such that disease incidence drops by as much as 28% in the case of men living in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

This effect is probably mediated in two ways. First, mitochondrial resilience and biogenesis, and the proteins optimized to consume oxygen to produce carbon dioxide and energy, are all increased by adaptation to high altitude. Second, as a result of the lower oxygen pressure, lactate production from glycolytic energy pathways drops precipitously, which in my speculation, is probably responsible for the lower incidence of diabetes, cancer, and heart disease. These diseases, especially diabetes, share the common diagnostic feature of increased lactic acid production coupled with lower serum (and breath) carbon dioxide.

Taking this into consideration, lastly, I’m going to enter the realm of pure speculation (to some) and say that, given Douglas Wallace’s intricate study of the modulation of the stress response in psychologically stressed rats, residing at altitude provides direct cognitive, energetic, and at times, survival competencies that aid the social behavior of peoples escaping state intrusion and domination. The complex forms of anti-authoritarian social organization, and the ability to address wide-ranging problems that for lowlanders requires e.g. centralized authority, 36 months, and a large budget, cannot happen if people don’t have a base level of food security, a good, healthy, plentiful environment, and thriving. Anything that aids this, as altitude seems to do, is indispensable. Stated more simply, residing at altitude confers energetic, health, and cognitive benefits that I think play a huge role for any group in the act of autonomous social organization. It’s not a coincidence that anti-authoritarians escaping the structure, simplicity, and violence of civilized life in a valley state live more complex lives at altitude – altitude aids their already existing desires.

Life may appear simpler when we lowland state inhabitants, embedded in our bureaucracies and technologies and structured urban life, hike up to a hill town to scenes of serene hill farms and animals and huts, but we who don’t have to make choices about how we get our water, how we get our food, and when a boss has outlived his welcome and can stop being a boss are the ones who actually have simpler lives. We’ve used the violence of bureaucracy and the state to artificially engineer possibilities out of existence. We have tamped down the complexity of our own lives with state bureaucracy and violence, but that will be a chat for another time.

As for what you can do with this information, besides running away from an oppressive valley civilization, acetazolamide, the B vitamins, aspirin, thyroid hormone, magnesium, have all been shown to increase oxygen consumption or carbon dioxide retention at sea level.

I personally try to spend at least a month every year in Santa Fe or Albuquerque, New Mexico, which are at 7200 feet and 5500 feet respectively.

Thanks for reading!

Bibliography

- “Zomia (Region).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 28 Dec. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zomia_(region).

- Scott, James C. Against The Grain: a Deep History of the Earliest States. Yale Univ Press, 2018.

- Scott, James C. The Art of Not Being Governed: an Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. Yale University Press, 2011.

- Dalton, Clayton. “Iron Is the New Cholesterol – Issue 67: Reboot.” Nautilus, 20 Dec. 2018, nautil.us/issue/67/reboot/iron-is-the-new-cholesterol.

- Wallace, Douglas C. “A Mitochondrial Paradigm of Metabolic and Degenerative Diseases, Aging, and Cancer: A Dawn for Evolutionary Medicine.” Annual Review of Genetics, vol. 39, no. 1, 2005, pp. 359–407., doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751.

- Wallace, Douglas C. “Mitochondrial Diseases in Man and Mouse.” Science, vol. 283, no. 5407, 1999, pp. 1482–1488., doi:10.1126/science.283.5407.1482.

- Martin Picard, Meagan J. McManus, Jason D. Gray, Carla Nasca, Cynthia Moffat, Piotr K. Kopinski, Erin L. Seifert, Bruce S. McEwen, Douglas C. Wallace. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Dec 2015, 112 (48) E6614-E6623; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1515733112

- Sapolsky, Robert. “Being Human: Life Lessons from the Frontiers of Science.” Guidebooks, guidebookstgc.snagfilms.com/1686_Being Human.pdf.

- Kahn, Sandra, and Paul R. Ehrlich. Jaws the Story of a Hidden Epidemic. Stanford University Press, 2018.

- “How to Change the Course of Human History.” Eurozine, 2 Mar. 2018, www.eurozine.com/change-course-human-history/.

- Mortimer, Edward A., et al. “Reduction in Mortality from Coronary Heart Disease in Men Residing at High Altitude.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 296, no. 11, 1977, pp. 581–585., doi:10.1056/nejm197703172961101.

- Weinberg, Clarice R., et al. “Altitude, Radiation, and Mortality from Cancer and Heart Disease.” Radiation Research, vol. 112, no. 2, 1987, p. 381., doi:10.2307/3577265.

- Winkelmayer, Wolfgang C. “Altitude and All-Cause Mortality in Incident Dialysis Patients.” Jama, vol. 301, no. 5, 2009, p. 508., doi:10.1001/jama.2009.84.

- Ramos, et al. “Patología Del Hombre Nativo De Las Grandes Alturas : Investigación De Las Causas De Muerte En 300 Autopsias.” PAHO/WHO IRIS, World Health Organization, iris.paho.org/xmlui/handle/123456789/15274.

- Bekbolotova, A. K., et al. “Effect of High-Altitude Ecological and Experimental Stresses on the Platelet-Vascular Wall System.” Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine, vol. 115, no. 6, 1993, pp. 636–639., doi:10.1007/bf00791144.

- “Report of the WHO/PAHO/IBP Meeting of Investigators on Population Biology of Altitude.” World Health Organization, WHO/PAHO/IBP, hist.library.paho.org/English/ACHR/RES7_4.pdf.

- Boljevic, S., et al. “Carbon dioxide inhibits the generation of active forms of oxygen in human and animal cells and the significance of the phenomenon in biology and medicine.” Vojnosanitetski pregled 53.4 (1996): 261-274.

- Apple, Sam. “An Old Idea, Revived: Starve Cancer to Death.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 12 May 2016, www.nytimes.com/2016/05/15/magazine/warburg-effect-an-old-idea-revived-starve-cancer-to-death.html.

- “Warburg Effect (Oncology).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 8 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warburg_effect_(oncology).

- Ou, L. C., and S. M. Tenney. “Properties of mitochondria from hearts of cattle acclimatized to high altitude.” Respiration physiology 8.2 (1970): 151-159.

- Shertzer, H. G., and J. Cascarano. “Mitochondrial alterations in heart, liver, and kidney of altitude-acclimated rats.” American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content 223.3 (1972): 632-636.

- Burton, Alan C. “Cancer and altitude. Does intracellular pH regulate cell division?.” European Journal of Cancer (1965)11.5 (1975): 365-371.

- Peat, Raymond F. “A Biophysical Approach to Altered Consciousness.” Journal of Orthomolecular Psychiatry 4 (1975): 189-97.

- Clayton, P.; Rowbotham, J. How the Mid-Victorians Worked, Ate and Died. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 1235-1253.