Power is not to be conquered, it is to be destroyed. It is tyrannical by nature, whether exercised by a king, a dictator or an elected president. The only difference with the parliamentarian ‘democracy’ is that the modern slave has the illusion of choosing the master he will obey. The vote has made him an accomplice to the tyranny that oppresses him. He is not a slave because masters exist; masters exist because he elects to remain a slave. -Jean Francois Brient

The great journalist Chris Hedges is no sycophant of power. Unlike the court-intellectuals David Brooks or Thomas Friedman, Hedges speaks iconoclastic truth to the most powerful empire of lies on the planet.

Hedges has risked his life reporting throughout the Middle East, Serbia, East Germany, and most recently he has explored the deepest pockets of poverty within the United States in his book (written with Joe Sacco) Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt. He has drawn great scorn from the establishment, an heir to Chomsky, criticizing Israeli apartheid in Palestine and US imperialism in the Middle East. He is also a champion of whistleblowers, supporting Bradley Manning and Edward Snowden, calling such sources the “lifeblood of journalism.”

Hedges, Noam Chomsky, Daniel Ellsberg and others have recently won a lawsuit against the Obama administration over the National Defense Authorization Act, which according to the judge Katherine B. Forrest, enables the government to carry out a repeat of Japanese internment by stripping US subjects of their (illusory to begin with) “rights,” which are really temporary privileges.

Again, Hedges is no coward when it comes to speaking truth to power, and risking his own life and reputation in the name of justice. But his political philosophy appears a bit conflicted.

In a recent interview on The Real News with Paul Jay, Hedges makes a seemingly radical argument about the appropriate relationship between the people and the monopoly on violence under which they live: In light of the fascist marriage of the Democratic and Republican party, who squabble over the details in the blueprint for corporation-state oppression, Hedges advocates a tactic of mass popular uprising, to keep the power elite afraid of the people.

“…[W]e as citizens have through the traditional structures of power been left powerless to respond. The only hope left is to get out in the street and build the kind of mass movements that I saw in countries like East Germany, where you had half a million people showing up in Alexanderplatz in East Berlin or half a million people showing up in the streets of Prague in Wenceslas Square during the Velvet Revolution, which I also covered.

I’m not naive enough to tell you it’s going to work, but appealing to the better nature of the Democratic Party, I can assure you is not going to work.

JAY: But doesn’t this mass movement need some kind of electoral strategy? Otherwise you wind up in a situation, don’t you, like what happened in Egypt, where Mubarak falls but there is no electoral strategy of the left in any place, so it’s the Muslim Brotherhood that winds up–. [Author: Yes, controlling the state, you were going to say.]

HEDGES: No. I’ve covered totalitarian states all over the world, and they all have elections.

JAY: No I didn’t–I said doesn’t it need an electoral strategy.

HEDGES: I’m not sure that it does. I think that the problem is–you know, and Karl Popper writes this in The Open Society and Its Enemies. He said the question is not how do you get good people to rule. Popper says that’s the wrong question. Most people, Popper writes, attracted to power are at best mediocre, which is Obama, or venal, which is Bush.

The question is: how do you make the power elite frightened of you? Who was the last liberal president we had? It was Richard Nixon–not because he was a liberal, but because he was frightened of movements. And there’s a scene–I think it’s in Kissinger’s memoirs, 1971, huge antiwar demonstration surrounding the White House, and Nixon has put empty buses, city buses end-to-end as a kind of barricade, and he’s standing at the window wringing his hands, going, Henry, they’re going to break through the barricades and get us.

And that’s just where you want power, people in power to be. And that’s why Sarkozy, who was a cretin, was unable to do too much damage to France, because if you got up in France and told French university students that they were going to pay $50,000 a year to go to college, they’d shut the damn country down.”

It sounds wonderfully insurrectionary, but in the very same interview Hedges applauds the incontestable, colossal power of the welfare state and advocates a strategy of taking power via the surrogate of the state.

How can Hedges have it both ways? How can he express skepticism toward Franz Oppenheimer’s political means and yet propose a more expansive state power as the solution?

‘Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defense of the rich against the poor, or of those who have some property against those who have none at all.’ – Adam Smith

Why doesn’t Hedges, like Chomsky, recognize that the gang of criminals called the state, which attempts to retain a perceived-legitimate monopoly on the use of violence in a given territory (as defined by Max Weber), is ultimately an unnecessary evil? That it does more harm than good?

Why doesn’t Hedges realize that free exchange is not the creator of his hollowed-out, poverty-stricken “sacrifice zones,” but state power buttressing the illegitimate claims of the capitalist class! Does the unfettered bazaar in Morocco or Thailand impoverish the buyers and sellers, or does the politically connected plantation owner, who crushes competition through the legal system?

And most pressingly, hasn’t Hedges read Markets Not Capitalism?!

“The State represents violence in a concentrated and organized form. The individual has a soul, but as the State is a soulless machine, it can never be weaned from violence to which it owes its very existence.” -Gandhi

The Unfreedom of Party Politics

Direct action is an old standby of the libertarian and authoritarian left, the front line in the labor wars of the early twentieth century. But a state of perpetual revolt, where a constant vigilance is the price of liberty, is not optimal. The goal is not to have to worry about the state becoming tyrannical, ever, because there would not be a state.

And while Hedges expresses skepticism about party politics, he speaks favorably of welfare states like Switzerland. Though a welfare state is preferable to a warfare state, both are ticking time bombs with varying fuse lengths.

No matter how utopian a welfare state seems today, the existence of a dormant behemoth, capable of “giving” (stealing at gunpoint and then redistributing) the people everything they want is fully capable of taking everything they have, including their lives. The welfare state, with its established bureaucracy and high tax-theft rate, is always liable to devolve into a warfare state, or an internally oppressive force after an upwelling of fascist sentiment.

Evident today with the fascist uprising throughout Europe, such liberal paradises as Sweden have witnessed the neo-fascist “Sweden Democratic” party win 11% in a poll last November. In Sweden, the grand state apparatus presently used to redistribute justice could soon be retooled as machine for mass brutality and repression.

“Unfortunately, this problem is not limited to Sweden. The story of the Sweden Democrats is the story of contemporary Europe. In Hungary, the Hungarian Guard of the Jobbik party continues to persecute Jews and Romani people. In Greece, Golden Dawn assaults parliamentary politicians and destroys businesses owned by immigrants.

In Coccaglio, Italy, the Lega Nord alliance announced a “White Christmas” during which police comb through neighborhoods in order to find immigrants without documents. In Norway, an outspoken supporter of the Sweden Democrats killed 77 people for their alleged “multiculturalism.” If the United States is progressing toward confronting its racist past, Europe seems to be spiraling deeper into the hideous pre-WWII cocktail of xenophobia and fascism. ” Daniel Strand, VICE, “The Iron Pipe of Swedish Neo-Fascism.”

When asked in an interview when the present form of state-capitalism will collapse, and whether the aftermath will result in positive social change, Noam Chomsky said, “The most civilized part of the world, with the highest cultural standards 70 years ago was Germany. No more need be said.”

The 1920s bout of hyperinflation in Weimar Germany, brought about by a punitive indemnity forced upon the German people with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, set the stage for the fascism in the ’30s. Today’s deepening global economic crisis (itself a premeditated $700B+ corporation-state heist of the tax-cattle cookie-jar) threatens to bring out the essential nature of temporarily net-benevolent European monopolies on violence, restoring states to their original and historical function:

“The idea that the State originated to serve any kind of social purpose is completely ahistorical. It originated in conquest and confiscation—that is to say, in crime. It originated for the purpose of maintaining the division of society into an owning-and-exploiting class and a propertyless dependent class—that is, for a criminal purpose.” —Albert Jay Nock

Hedges wishes to keep those in power afraid of the people. But why is it necessary to have rulers at all? Why can’t people (in the absence of state-conferred elite privilege, artificial scarcity, and the protection of illegitimately acquired property) voluntarily organize their own, decentralized institutions? (Actually, they already have, to great effect — worker cooperatives globally employ 20% more people than multinational corporations).

Mass Mobilization

Anarchists don’t seek to work “within” the system — because people are suffering now and it is bourgeois to seek incremental, comfortable change while making ethical compromises with the established order. The statist tactic is to take power through the political system (which often results in co-optation and only rarely concessions like authentic welfare provisions that are inevitably exploited by corporations, like the Medicare Prescription Drug Act or agricultural subsidies for Monsanto). Hedges himself acknowledges that the welfare state is a concession designed to keep the overall capitalist architecture intact:

“I mean, Roosevelt was a compromise figure. You had the Communist Party, you had the Progressive Party, you had anarcho-syndicalist unions like the Wobblies, you had a radical left that was putting pressure [on him]. So Roosevelt says that his greatest achievement is that he saved capitalism. And he’s right. And most of the policies that he adopted he took from the left.”

The corporation state takes a dollar of labor from the masses and gives them back a mere fraction — breaking their legs and handing out crutches. We ought not to settle for the opiate of superficially redistributive justice — but cast off the chains that make such redistribution necessary in the first place!

“If employers can’t be trusted with power, how on earth can politicians and bureaucrats be so? The solution is to smash the structures of government-imposed privilege that put workers into a position of dependency on employers in the first place.” -Roderick T. Long, Bleeding Heart Libertarians, Libertarianism Means Worker Empowerment

Even if we elected a modern Eugene Debs– who Hedges rightfully admires– power corrupts, and politicians who sound populist one day are revealed puppets of the power elite the next.

The problem of faithful representation is yet another fault with the strategy of seeking to control state power, which, like nuclear energy, can be used for good but, like clockwork, when the inevitable meltdown/bombing takes place, risk appears to outweigh the benefits.

States, through the psuedo-racism of nationalism, regularly commit democide and there is no reason to believe this millennial trend will reverse any time soon.

The other, libertarian strategy is to, in the words of radical labor group the Industrial Workers of the World, “build a new system within the shell of the old.” Rendering the old system obsolete — withdrawing consent in any way possible, and becoming antifragile to the inevitable blunders and institutionalized psychopathy of the corporation-state.

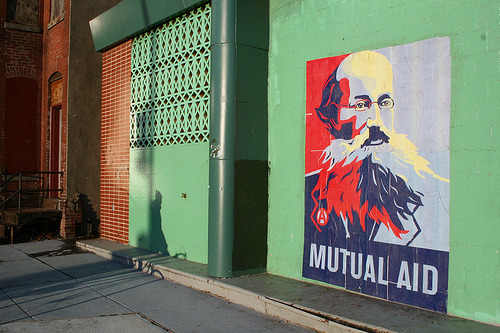

Worker cooperatives, polycentric legal orders, technologies of liberation, and mutual aid organizations are capable of accomplishing all the social good of states without the systematic violence and ever-present threat that psychopaths will steal everyone’s labor product, propagandize them with state-schooling and controlled media, and send them off to kill the poor subjects of another state.

Democracy Without The Threat of Violence

“Good people don’t need laws to tell them to act responsibly and bad people will find a way around the laws. ” – The Ages

What happens in the vacuum of state power? Not chaos but peace. Communes, eco-villages and intentional communities are stateless — nobody goes hungry and disputes are resolved without bombs or embargoes. Zomia is stateless. The kibbutzim are stateless within a rather nasty state. The Paris Commune of 1871 was a rejection of statism. Against all odds, an effective libertarian socialist militia was raised against a well-funded fascist military during the Spanish Civil War of 1936-9, and under the control of the workers several agricultural and medical advancements were made.

There are many examples of authentic democracy arising, like the Occupy movement’s organizational structure — and that is what really terrifies the state. But does anarchy, the absence of rulers, mean chaos and violence? Can any non-mechanized, localized violence ever compare to dropping nuclear bombs on cities full of innocent people? On the contrary, it appears when people take power directly, not through the surrogate of an elite statist class, peace and property ensue.

“Anarchists take an entirely different view of the problems that authoritarian societies place within the framework of crime and punishment. A crime is the violation of a written law, and laws are imposed by elite bodies.

In the final instance, the question is not whether someone is hurting others but whether she is disobeying the orders of the elite. As a response to crime, punishment creates hierarchies of morality and power between the criminal and the dispensers of justice. It denies the criminal the resources he may need to reintegrate into the community and to stop hurting others.

In an empowered society, people do not need written laws; they have the power to determine whether someone is preventing them from fulfilling their needs, and can call on their peers for help resolving conflicts. In this view, the problem is not crime, but social harm — actions such as assault and drunk driving that actually hurt other people.

This paradigm does away with the category of victimless crime, and reveals the absurdity of protecting the property rights of privileged people over the survival needs of others. The outrages typical of capitalist justice, such as arresting the hungry for stealing from the wealthy, would not be possible in a needs-based paradigm.

During the February 1919 general strike in Seattle, workers took over the city. Commercially, Seattle was shut down, but the workers did not allow it to fall into disarray. On the contrary, they kept all vital services running, but organized by the workers without the management of the bosses.

The workers were the ones running the city every other day of the year, anyway, and during the strike they proved that they knew how to conduct their work without managerial interference. They coordinated citywide organization through the General Strike Committee, made up of rank and file workers from every local union; the structure was similar to, and perhaps inspired by, the Paris Commune.

Union locals and specific groups of workers retained autonomy over their jobs without management or interference from the Committee or any other body. Workers were free to take initiative at the local level. Milk wagon drivers, for example, set up a neighborhood milk distribution system the bosses, restricted by profit motives, would never have allowed.

The striking workers collected the garbage, set up public cafeterias, distributed free food, and maintained fire department services. They also provided protection against anti-social behavior — robberies, assaults, murders, rapes: the crime wave authoritarians always forecast.

A city guard comprised of unarmed military veterans walked the streets to keep watch and respond to calls for help, though they were authorized to use warnings and persuasion only. Aided by the feelings of solidarity that created a stronger social fabric during the strike, the volunteer guard were able to maintain a peaceful environment, accomplishing what the state itself could not.

This context of solidarity, free food, and empowerment of the common person played a role in drying up crime at its source. Marginalized people gained opportunities for community involvement, decision-making, and social inclusion that were denied to them by the capitalist regime. The absence of the police, whose presence emphasizes class tensions and creates a hostile environment, may have actually decreased lower-class crime.

Even the authorities remarked on how organized the city was: Major General John F. Morrison, stationed in Seattle, claimed that he had never seen “a city so quiet and so orderly.” The strike was ultimately shut down by the invasion of thousands of troops and police deputies, coupled with pressure from the union leadership.

In Oaxaca City in 2006, during the five months of autonomy at the height of the revolt, the APPO, the popular assembly organized by the striking teachers and other activists to coordinate their resistance and organize life in Oaxaca City, established a volunteer watch that helped keep things peaceful in especially violent and divisive circumstances. For their part, the police and paramilitaries killed over ten people — this was the only bloodbath in the absence of state power.” (115-117, Anarchy Works (PDF), Paul Gelderloos)

Hedges should heed his Occupy comrade, the great anarchist anthropologist David Graeber, when he writes

“The theory of exodus proposes that the most effective way of opposing capitalism and the liberal state is not through direct confrontation but by means of what Paolo Virno has called ‘engaged withdrawal,’ mass defection by those wishing to create new forms of community.

One need only glance at the historical record to confirm that most successful forms of popular resistance have taken precisely this form. They have not involved challenging power head on (this usually leads to being slaughtered, or if not, turning into some—often even uglier—variant of the very thing one first challenged) but from one or another strategy of slipping away from its grasp, from flight, desertion, the founding of new communities.” (60-61) Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology

Translations for this article:

- Portuguese, Tomada do Poder Com ou Sem Chris Hedges.