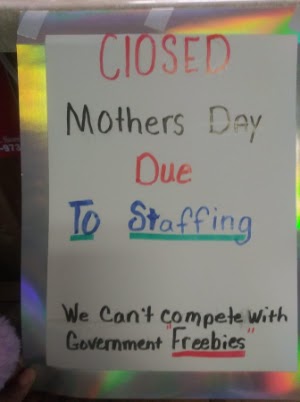

Unless you’ve been under a rock the past month or so or are a total social media abstainer, you’ve seen some of the worst people on earth whining about how “nobody wants to work any more!” Indeed, so great is the outrage of many that only putting angry signs in the window of their business establishments could sufficiently express it.

While it’s questionable how appealing the message was to prospective employees, there’s no doubt their discomfiture has contributed enormously to the enjoyment of folks like me on Twitter and Facebook.

But now they’ve found a champion in Richard Ebeling, of the American Institute for Economic Research. Not exactly a surprise; promoting the interests of the worst people on earth is, after all, AIER’s mission. But it’s more than a matter of duty for Ebeling. One evening not long ago, as he recounts (“The Labor Shortage Is a Government-Contrived Scarcity,” AIER, June 14), it became personal. Wishing only to enjoy a sit-down restaurant meal with his wife, he found his hopes dashed by the no-goodniks who refused to accept employment on the terms the employer saw fit to offer them.

No doubt not only Ebeling but also the owner of the Thai restaurant in question — heir to would-be employers similarly disdained by sturdy rogues and masterless men going back to Tudor days — would have sympathized with Hines, the farmer of thirty thousand acres in The Grapes of Wrath who said “A red is any son-of-a-bitch who wants thirty cents an hour when we’re payin’ twenty-five!”

As for Ebeling, he wants to make it clear this lack of sufficient staffing for sit-down service didn’t just happen. It was contrived! By the government! Mr. Ebeling’s dinner didn’t die, it was killed. And the people who killed it have names and addresses.

On the face of it, it is a puzzlement why so many jobs go vacant. “There are plenty of job openings; it is a failure of a good number of employable people not being interested in filling the slots employers would like to fill. Why?”

Some have argued it’s because employers are too cheap; that is, they are unwilling to pay a wage high enough to draw unemployed workers back into the active labor force. The problem with this latter explanation is that it does not make clear why wage “x” at which some of these workers were willingly employed 15 months ago is now unacceptable just a little bit more than a year later, given the lost income experienced during all that time.

The real answer, he says, is that because of extended, and higher than average, unemployment benefits, workers get paid as much — or sometimes more — for staying home than they do for working.

But Ebeling has it backward. It’s the capitalist status quo that is artificial. He might better have asked why it was, in the previous state of affairs — one which he regards as normal — that people dragged themselves daily into jobs which they dreaded with every fiber of their being. The answer, of course, is that it was the only alternative to homelessness or starvation.

But it’s that previous state of affairs, the one to which he longs for a return, which was contrived by the government. It was a government-contrived labor plenitude, resulting from a government-contrived scarcity of working-class access to the means of production.

The state of affairs Ebeling considers normal capitalism is only possible because of centuries of state violence. It was founded on state violence, and it continues to exist because of ongoing state violence.

In England it began with the late medieval and early modern seizure of arable land in the open fields, and its enclosure as sheep pasturage. Peasants were robbed of customary access rights to the land, rack-rented and evicted. Throughout this entire process, the employing classes depended on state violence to force the newly landless laborers to work for wages on whatever terms were offered, with whippings, mutilation and peonage for any who refused. The land robbery continued with Parliamentary Enclosures of common pasture and waste in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century.

Capitalist employers continued to rely on totalitarian social controls by the state to enforce discipline on the work force. The Laws of Settlement functioned as an internal passport system. In addition to the Combination Laws, the state also prohibited free association among workers by criminalizing friendly societies and benefit societies, fearing they would become breeding grounds for radicalism or that their benefits might be used as de facto strike funds. As J.L. and Barbara Hammond described it, English society was “”taken to pieces … and reconstructed in the manner in which a dictator reconstructs a free government.”

Meanwhile, as capitalism spread, customary peasant rights to the land were nullified first in Europe, and then the parts of the world colonized by Europe. In case after case — Hastings’ Permanent Settlement in Bengal, the hacienda system in Latin America, and so on, throughout the entire colonized world — ordinary people were robbed of their right to self-employment on the land so they’d work for capitalist employers.

As for the so-called “laissez-faire” era, such strict social controls, slavery, tariffs, etc., were not abolished because people just suddenly realized they were bad ideas, because they understood economics better. No, the capitalist state stopped doing these things because they were no longer needed. The systems of power they had been necessary to create were securely established. What need for trade barriers, for example, when the British had consolidated half the resources and markets of the world under the control of their Empire, their merchant fleet had a monopoly on shipping within it, and they’d thoroughly suppressed any threat of competition from the Indian textile industry?

Meanwhile, despite pretensions of laissez-faire, the state continued to enforce the artificial scarcities and artificial property rights that were most central to the survival of capitalism. To this day, it enforces absentee title to land on behalf of the heirs and assigns of the robbers described in preceding paragraphs. The American state and its allies maintain a global empire to keep governments in power that will enforce title to the land and resources looted under colonialism, and help keep labor cheap. The state enforces the patent monopolies which enable global corporations to enclose outsourced production within corporate legal walls, and maintain a legal monopoly over disposal of the product — a form of protectionism on which global capitalism is as dependent as national capitalism was on the tariff a century ago.

The state encloses the credit commons, thereby giving owners of stockpiled wealth a monopoly on the right to provide funding for business enterprise — and hence on organizing productive activity. This is why Elon Musk is praised as a “genius,” despite designing or inventing absolutely nothing himself. His control over the finance function enables him to enclose the cooperative labor and social intellect of others, take credit for it, and extract rents from it.

A polemicist for working class interests two hundred years ago — a sort of Evil Spock universe mirror-image of Ebeling — might have asked the inverse of his question: Why were laborers more willing to work for wages after enclosure and expropriation than they were before, despite the fact that the wage on offer had not risen and the price of bread had not fallen.

The answer, again, is simple: So long as they had access to independent subsistence on their customary share of arable land in the open field, to common pasturage and to wood and game in the common waste, laborers were unwilling to work for the wages employers saw fit to offer. But once they were robbed of those independent means of subsistence, the choice became one between accepting work for whatever wages were offered — no matter how low — and starvation.

Indeed a central problem of capitalist political economy, going back to Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees, has been how to put laborers in a position where the only alternative to accepting work on the employer’s terms is starvation.

Achieving this state of affairs was the conscious goal of the agrarian capitalists who agitated for and carried out the enclosures. They knew, and said out loud, that so long as people could feed themselves on their own common land, they would refuse to work for the land-owning classes as long, as hard, or as cheaply as the latter desired. They knew, and said out loud, that the owning classes could exploit the laboring classes as mercilessly as they desired, once the only alternative to employment was starvation.

They really did say this out loud. Here are a few examples from contemporary polemical literature by the propertied classes in England during the period of Parliamentary Enclosures:

A pamphleteer in 1739 argued that “the only way to make the lower orders temperate and industrious… was ‘to lay them under the necessity of labouring all the time they can spare from rest and sleep, in order to procure the common necessities of life’.”

A 1770 tract called “Essay on Trade and Commerce” warned that “[t]he labouring people should never think themselves independent of their superiors…. The cure will not be perfect, till our manufacturing poor are contented to labour six days for the same sum which they now earn in four days.”

Arbuthnot, in 1773, denounced commons as “a plea for their idleness; for, some few excepted, if you offer them work, they will tell you, that they must go to look up their sheep, cut furzes, get their cow out of the pound, or perhaps, say they must take their horse to be shod, that he may carry them to a horse-race or cricket match.”

John Billingsley, in his 1795 Report on Somerset to the Board of Agriculture, wrote of the pernicious effect of the common on a peasant’s character: “In sauntering after his cattle, he acquires a habit of indolence. Quarter, half, and occasionally whole days are imperceptibly lost. Day labour becomes disgusting; the aversion increases by indulgence; and at length the sale of a half-fed calf, or hog, furnishes the means of adding intemperance to idleness.”

Bishton, in his 1794 Report on Shropshire, was among the most honest in stating the goals of Enclosure. “The use of common land by labourers operates upon the mind as a sort of independence.” The result of their enclosure would be that “the labourers will work every day in the year, their children will be put out to labour early, … and that subordination of the lower ranks of society which in the present times is so much wanted, would be thereby considerably secured.”

John Clark of Herefordshire wrote in 1807 that farmers in his county were “often at a loss for labourers: the inclosure of the wastes would increase the number of hands for labour, by removing the means of subsisting in idleness.”

They sound just a little bit like those restauranteurs with the “No One Wants to Work Any More” signs, don’t they?

The sacred “property rights,” to whose defense right-libertarian think tanks like AIER pledge their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor, are the property rights of the heirs and assigns of the robbers who carried out these expropriations. The primary exigency against which they defend these property rights is the heirs and assigns of the robbed taking it all back.

In England 250 years ago, spokespersons for the propertied classes commonly argued that “the nation” would benefit if labor were sufficiently disciplined out of its indolence, and wages lowered so that laborers would be forced to work six days for the same subsistence previously provided by poor. Never mind that for the overwhelming majority of the population who were forced to work for wages it most decidedly not be a benefit.

As an indication that things have not changed, and today’s right-”libertarians” have taken up the mantle of the above-mentioned propertied classes of the 18th century, Reason today published a commentary with the headline “California, New York Have the Most To Gain From Ending Bonus Unemployment Benefits.” The whole thing is just glowing reports of how many more people were forced to accept jobs on the bosses’ terms where the extra payments were cancelled. Now, it might have occurred to you that workers are benefiting from the extra payments right now because businesses are being forced to raise wages and otherwise make work more attractive, and that workers are the overwhelming majority of the actual people in California and New York. But when right-”libertarians” say California and New York stand to gain, of course they mean the property owners and employers of New York — just as their spiritual ancestors did when they spoke of “the nation” 250 years ago.

Ebeling writes that programs like unemployment payments create “a false ‘opportunity cost’ for those in these labor categories in terms of their trade-off between work and non-work.”

I say “false” due to the fact that if these redistributive programs were not present, lower-skilled workers would have to weigh differently the income forgone by not accepting gainful employment versus perhaps not earning anything. Instead, for as long as these types of programs are in effect, they, basically, establish a “floor” below which more is lost by working than taking a job.

But again, he has it backwards. It was the state, in league with capitalist employers, which distorted the opportunity cost calculus by destroying the floor below which more was lost by working than taking a job.

Ebeling continues with a homily on how things naturally work “in the competitive free market,” as opposed to the “contrived scarcities” and “contrived plenitudes” which are created by government. He makes it clear that, in his framing of things, it’s the current unwillingness of workers to accept jobs at the existing wage that’s the “contrived scarcity,” as opposed to the previous natural competitive “free market” state of affairs in which workers accepted whatever jobs they were offered and were by-god thankful. It’s always the income transfers from rich to poor that distort things, and the situation that would otherwise prevail if the bargaining power of labor weren’t artificially increased at the expense of capital that’s natural. If it weren’t for all this socialistic intervention by the government on workers’ behalf, we could go back to the natural competitive “free market” state of affairs where things were better for employers and worse for workers.

Ebeling’s argument is essentially a slightly more intellectualized version of Robert J. Ringer’s “Quick as Hell Full Employment Theory”: do away with welfare benefits, food stamps, and unemployment insurance, and everyone will get a job quick as hell.

But the truth is the exact opposite. The role of the state under capitalism is to create a plenitude of workers competing for available jobs which is contrived, not natural. The primary form of government intervention is to make alternatives to wage labor artificially inaccessible for labor, and to make the means of production artificially scarce. The capitalist state’s central direction of intervention has been to enforce artificial scarcity rents on land, capital, and credit, and facilitate the extraction of rents by the propertied classes. The predominant flow of income enabled by the state has been overwhelmingly from poor to rich.

Whatever flows of income take place in the opposite direction — welfare, minimum wage laws, and the like — are entirely secondary, and reflect the capitalist state’s response to the survival imperatives of capitalism itself.

So reality is directly contrary to the right-libertarian framing of a “normal” system in which capital is accumulated in a few hands, the means of production are absentee owned, and most people work for wages, with occasional disruptions by government intervention that weakens the employers’ prerogative and makes things slightly less shitty for workers.

What Ebeling considers normality, the balance of power between workers and employers that prevailed before expanded unemployment benefits, is the artificially constructed situation. The state of affairs he complains of, as the alleged result of expanded and extended unemployment benefits, is just a pale imitation of the state of affairs that prevailed naturally before the enclosures.

Thus we see, at its heart, the true nature of the right-libertarian project: to frame as “natural,” or “voluntary” a system which was coercive in its foundations and remains coercive in its core logic. To see what I mean, just try a little thought experiment. Read the wretched little pamphlet “I, Pencil,” supposedly a celebration of the magic wrought by “voluntary exchange” in bringing together the components of a pencil from all over the world. As you read through it, stop every time you see some particular material mentioned and pay attention to where it comes from. Pay special attention if it’s a natural resource in an area that was colonized by a settler state like the U.S., or by a European colonial empire, at the time Leonard Read wrote it or shortly before.

When I say right-libertarianism seeks to frame a system created by violence and coercion as “voluntary,” it’s not just a throwaway line. It’s something that can’t be stressed enough. It’s at the heart of the capitalist ideological project. Capitalist ideology is full of nursery fables, Robinsonades, and just-so stories: private property arose from peaceful appropriation and separation from the common via admixture of labor; economies dominated by commodity production for the cash nexus came about as the result of a human “propensity to truck, barter, and exchange”; the dominance of specie currency was a natural and spontaneous response to the problem of “dual coincidence of wants.” Etc.

For anyone who is genuinely libertarian — that is, interested in maximizing individual agency against authoritarian institutions like state and capital, as opposed to the kind of “libertarians” who slavishly defend the wealth of robbers and an artificial model of “private property” imposed by early modern states — increasing workers’ ability to refuse work until they’re paid better, or to live comfortably with less or no wage labor, should be the goal.

Things like eviction stays, extended unemployment, welfare, minimum wages, and the like, are what happens when the forms of privilege enforced by the capitalist state become destabilizing, and the state (as executive committee for the interests of capital) must intervene to prevent homelessness, starvation, and collapse of aggregate demand from destroying capitalism. These secondary interventions leave workers better off than if they didn’t exist, but they’re nowhere near equal to the amount of robbery workers undergo through the primary state interventions of enforcing privilege for capitalists and landlords.

I’m certainly not going to agitate for the removal of such secondary interventions until the primary ones are eliminated, because they’re no more than a state limit on the abuse of its own grants of power. So long as the grants of power and privilege remain in effect, I will cheer on whatever way workers find to leverage them for their own empowerment.

But as I said before, whatever limited empowerment workers have from the benefits Ebeling complains of are but a pale, feeble shadow of the power they had before they were robbed by the state and capital in collusion. Our goal should be to undo the robbery itself: to nullify absentee titles not founded in occupancy and use, to tear down enclosures of the credit commons that give the owners of wealth a monopoly on providing the liquidity needed to finance productive enterprise, and to put labor back in possession of its own.

Our goal, in short, should be the state of affairs that Ebeling and those sorehead employers complain of — a state of affairs in which workers set the terms, and are in a position to withhold their labor until those terms are met — only more so, everywhere, and all the time.