Andrew turned suddenly toward Julia and, with the distinct disdain for anything ‘liberal’ that identified him as either a leftist or a conservative, spoke bluntly: “You care so much about the environment that you don’t even care about people. Are people in the ‘third world’ just supposed to give up factories? I’m not saying the first world is somehow morally superior, but those countries in Latin America and Africa need to get to our level before they can worry about the environment.”

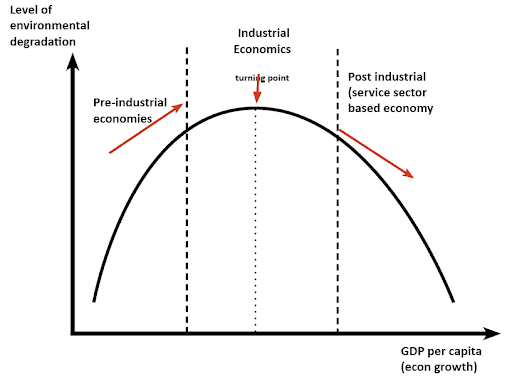

Julia sighed and stared around the tiny classroom—the five by six row of classic desk-chairs, the chalkboard taking up an entire wall, and the rest of the room, both carpet and wallpaper, a faded green. It had been a half hour since their economics class had ended and they were still arguing. The seed of the debate had begun during a discussion on economic development in Latin America compared to that in the rural U.S. South. Andrew, an economics student, argued cynically for the necessity of industrial capitalism in all parts of the world to raise people out of poverty and apparently improve people’s lives with technology. Julia had not yet declared her major but had a keen interest in anthropology and a strong distrust of capitalism common in many students of liberal arts colleges, and had therefore squared off against Andrew. That’s how they ended up where they were now. “So, the Kuznets Curve? The environmental version?” she asked.

“Yes, exactly. Developing regions can’t be concerned about environmental impacts while they’re… well, developing. They need to get out of poverty first. This even follows a sort of Marxist thinking. You can’t get to socialism without going through capitalism first. Look what happened when they tried to skip that step in Russia or China.”

“I thought you liked China. Isn’t it sort of your dream of a hyper-capitalist nation-state?” Julia had known Andrew for about two years and she still wasn’t sure what his political leanings genuinely were—he praised capitalism but was perfectly willing to think beyond it if it went toward furthering technology and industrialization; a sort of non-partisan accelerationist.

“I like China now,” Andrew retorted, “but that’s only because they eventually saw the error of their ways and embraced capitalism as a necessary part of development. They’re Marxist materialists governing a capitalist super-economy.”

“Ok, well let’s say you’re right and countries in the Global South have to go through capitalist development. What does that even mean? Capitalism isn’t one thing, it’s a whole set of productive, reproductive, and transactional structures and relationships.”

Andrew thought about it for a moment, then his eyes lit up. “Well you know… like the traditional economic growth model. Third world countries need industrialization, intensive large-scale agriculture, microcredit, expansion of export markets, a certain degree of healthcare and educational infrastructure. We’ve talked about this in econ.”

“Well… the infrastructure sounds good in theory” responded Julia—her decentralist opinions making her feel conflicted—“but you know that’s just to ensure they have a solid labor pool, not for any kind of good-will or desire for individual upward mobility. And anyway, why do you assume all development has to follow a capitalist path?” Before Andrew could respond, Julia continued, “It’s like Noam Chomsky argues: that model of market development isn’t even how America developed—it was through state-sponsorship and monopolies—and we’ve just forced an ahistorical economic ideology on other countries so they can become export economies for the United States.”

“Ok but… but… what about that one guy’s book… Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth! He’s a Marxist and he argues that people are like trapped between understanding decolonization as moving backward to precolonial history or moving forward into capitalism. Right?”

Julia looked at him aghast. “You’ve never even read that book, have you? Fanon argues that there’s no movement backward to a pre-colonial national identity but that means national cultural and international struggle against the global class system are directly linked. He is not arguing for some kind of pseudo-decolonial Kuznets Curve.”

“I… I… well what does that have to do with environmentalism anyway?” responded Andrew, clearly taken aback by the callout.

“EVERYTHING!” Julia shouted with exasperation. “Your whole argument about development basically requires environmental degradation. You keep talking haphazardly about Marxism, but you forgot the whole eco-Marxist critique that environmentalism gets co-opted into capitalism in a way that makes it ineffective. Even putting aside Chomsky’s whole point about development in the Global South being essentially imperialism, the Environmental Kuznets Curve doesn’t really work as a model of ‘pro-national’ development because it gets co-opted and the interests of foreign capital are ultimately put first!”

“Ok” Andrew huffed, “let’s say you’re right. What alternative is there to capitalist development?”

“Well that’s a really loaded question. My whole point is kind of that there isn’t one path of development. That’s the capitalist propaganda you’ve been spouting,” Julia seemed to wonder out loud as Andrew rolled his eyes. “I guess the first thing I’d return to is Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, because although you can’t go back to a pre-colonial condition that doesn’t mean that all cultural institutions are totally and irreparably defunct. They still exist and they’re still important. Think about substantivist economic anthropology.” Andrew looked confused so Julia continued, “Look I know you’re just an economics major, but haven’t you at least encountered economic anthropology?” Andrew remained silent. “Ok well, substantivist or institutionalist economic anthropologists like Karl Polanyi and students of his thinking assert that economics isn’t just about rational choices and individual decision making, but that institutions emerge from particular material conditions and help constitute diverse kinds of economies. Gift-giving or reciprocity requires kinship structures or, if it’s a primary mode of economic life, community centers of distribution or something like that. Even capitalism is forcibly constituted by the institution of the state.”

“Ok now you’re just going off on a tangent!” Andrew interjected.

“No, wait! Let me finish!” Julia insisted. “If the substantivists or the institutionalists or whatever you want to call them are at least partially right, then one project for non-capitalist development could be to strengthen traditional cultural institutions to allow local people to govern and manage their resources instead of forcing a capitalist logic onto them.”

“And this helps the environment, how?”

“Well going back to talking about development particularly in the Global South…” Julia quickly continued, “I don’t want to universalize the cultural views of diverse and varied people—especially Indigenous folks—but many traditional institutions have a great reverence for nature. Just look at the Indigenous peoples of the Amazon—to choose a really clear example. They live in general harmony with the Amazon rainforest, in some ways see themselves as ontologically on the same level as other things in nature like birds and leopards and trees. Those non-human entities don’t represent not resources but other people that just act and think somewhat differently than humans. Eduardo Kohn has a whole book called How Forests Think, which explores this idea.”

Andrew looked bewildered. “So, they think trees are people?”

Julia rolled her eyes. “You’re oversimplifying it. What I’m saying is that, in the case of many Indigenous Amazonian tribes, nature isn’t ‘outside.’ It’s ‘inside’ and so just as much a realm of perspective, thought, obligation, reciprocity, and exchange as human society is. And this is reflected in their cultural practices, the way they live out horizontal politics, and how they resist deforestation and colonial violence. And this may not be a universal outlook among ‘non-western’ people but similar insights echo across numerous cultures in Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. That’s why it’s so important that the new president of Brazil Lula is naming Indigenous Amazoninans as ministers and even promising a Ministry of Indigenous Peoples. It’s a step toward not just helping to defend Indigenous rights but placing them in positions where their cultural and environmental insights can be expressed politically.”

Andrew sat and pondered this for a moment, the silence only broken by the ticking of the analog clock essential to any classroom. “Ok, but you prefaced that whole thing by saying that, or I guess saying that Fanon says, you can’t go back to a pre-colonial system. Doesn’t that contradict your whole substantivist-thing argument?”

Julia responded quickly, clearly expecting the retort. “I’m not saying that people need to go back. These ‘non-colonial’ social networks, trade hubs, commonly held land, etc. and even many ‘semi-colonial’ cultural institutions—like liberation theology churches—still positively define the lives of millions of people; they have just been encroached upon by capitalism, forcing them to become secondary aspects of economic life. But yes, you have a point… sort of. I’m only willing to give you some credit.” Julia chuckled as Andrew scowled. “You can’t just revitalize older intuitions. Not only would that, in my opinion, be ineffective as a whole, it’s also largely undesirable. I don’t think people want to give up technology and such and go back to a romanticized ‘simpler time,’ not to mention that some traditional intuitions in many parts of the world restrict individual freedom or place women in a subordinate position or have some kind of racial hierarchy or caste system. You need to look backward but also move forward. That’s where the solidarity economy comes in.”

“The what economy?” Andrew asked.

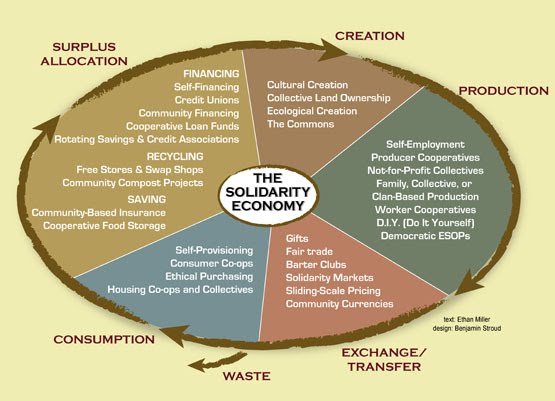

“Do you not know anything beyond mainstream economics? Anything at all?” Julia scoffed and then, seeing Andrew’s face, quickly apologized. “Sorry, so the solidarity economy is an idea originating in Latin America that’s basically a catch-all term for the creation of a non-capitalist network of institutions and practices—as opposed to centrally planned socialism. This means worker cooperatives, consumer cooperatives, mutual aid networks, community workshops, makerspaces, local currencies, credit unions, mutual banks, commons, fraternal benefits societies, et cetera.” Julia’s eyes lit up. “Oh oh oh! And if the capitalist market is forcibly maintained by the institution of the state then the ‘market’ of the solidarity economy can be non-coercively reinforced by the communitarian institutions that the substantivists talk about! It’s like David Graeber! The anarchist anthropologist! He argues that markets without state violence and underpinned by the the ‘communism of everyday life’ can become the basis of freedom!”

Andrew opened his mouth, but Julia cut him off again. She was on a tangent. “And before you ask, ‘what does that have to do with the environment?’ again, let me continue. It’s related to the environment for a whole bunch of reasons. Cooperatives tend to be more concerned about the local environment because the people who own them—workers and/or consumers—usually live in the community where the business exists. Local currencies encourage people, through discounted prices, to buy locally which once again stimulates businesses concerned with the local conditions. Community workshops encourage people to not buy individually and therefore create large demand for industrial tools and also to not just replace things that break but fix them instead. And one of the biggest ways this affects the environment is, like our professor argues, that it forces people to think about themselves and their environment as mutualistically connected. They are a community that must maintain itself both through production and allocation of goods and services and through the maintenance of ecological health.” Julia was almost out of breath, but she continued on, “If you could couple this idea of solidarity economy… with the substantivist-inspired argument of revitalizing community institutions networked with system of community self-defense and radical working class collective action that, like Fanon insists, doesn’t exclude peasants or the lumpenproletariat… you could generate a kind of development that is non-capitalist, non-reactionary, and decentralized, and that completely circumvents the Environmental Kuznets Curve; no forcible expansion of industrial agriculture, no expansion of export markets, a networked infrastructure that is culturally appropriate and made by the people for the people instead of by capitalists to increase the usefulness of laborers.”

Andrew looked surprisingly interested, but still massively skeptical. That was ok, Julia didn’t expect to convince him (or herself) in one conversation. She hadn’t even fully conceptualized this idea until the debate had spilled over from class. After a moment Andrew spoke, “It’s a nice theory, but where is there an example of this or something similar occurring in real life though?”

Julia was ready for this question too. The answer had occurred to her when she had first brought up Indigenous peoples. “The Zapatistas! Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional! In Chiapas, the southernmost state in Mexico, the Zapatistas are combining Indigenous Mayan traditions with Marxist and anarchist theory and Mexican revolutionary influences like Emilio Zapata and Pancho Villa to create their own autonomous society. If I remember correctly, they formed from a combination of Indigenous Mayans resisting NAFTA and Mexican Marxist guerillas. That’s a practical beginning of a model for economic development that is, again, non-capitalist but utilizing markets, non-reactionary but culturally-appropriate, non-statist and producer-controlled, ecological, decentralized, et cetera.”

Andrew looked at the clock, they had now been arguing for way too long. “Look, you can go fight your green-red-black revolution in Mexico. I have to go to my next class.” He walked out of the room, defeated but unconvinced. Julia smiled the kind of smile you get to have when you’ve come across a new idea… or at least new to her.