Libertarian authors often point to historical examples of societies (or aspects of societies) that putatively approximate their political ideals. Some popular examples of polycentric or quasi-polycentric legal regimes and/or decentralized property arrangements include Anglo-Saxon England,¹ ancient and medieval Ireland,² the American frontier,³ and Iceland’s Free Commonwealth period,⁴ among others.

My purpose here is not to go into whether or not it’s accurate to point to elements of these periods as embodying such ideals, but rather merely to bring awareness to another intriguing historical period: the Frisian Freedom from 1101–1523. I’m surprised considering this habit to not already have seen it receive attention from a libertarian perspective.

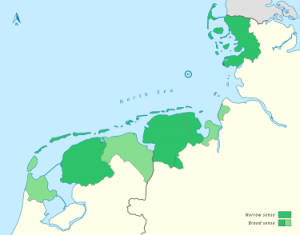

Most modern Frisians (unsurprisingly found most numerously in the province of Friesland,⁵ but noteworthy numbers are also found in other Dutch and German areas corresponding to their historical domain) are the descendants of a west germanic people that inhabited a region roughly encompassing the northern Netherlands and northwestern Germany, and which itself traces its lineage back to groups like Angles and Saxons that settled said region around the 6th century AD.

Though more recent scholarship has taken a more skeptical turn on this matter, the Frisian languages are still widely regarded as the English language family’s⁶ closest living relative.

An interesting wrinkle in Frisian history I’d like to draw attention to is the period of Frisian Freedom. In this era, serfdom and the feudal system were apparently absent. Interestingly this society is thought to have existed from the 12th to the early 16th century—solidly into the early modern era—the era coming to a close when Frisia became part of the Habsburg Netherlands; that’s almost a century longer than the much-studied Free Commonwealth period. It should also be noted that the conditions which allowed for the rise of Frisian Freedom are thought to go back much farther, all the way back to the 9th century.⁷

Of course, the absence of feudalism and serfdom does not guarantee that Frisia during this period was a model libertarian society at the policy or legal level—let alone anarchistic—however at the bare minimum I think the relative freedom in this era warrants attention from a specifically libertarian perspective,⁸ looking into questions such as what the internal politics, law, and economy were like; the truth behind the claims regarding the nonexistence of serfdom; the factors that allowed for its relative longevity; and, of course, how close it comes (or doesn’t come) to embodying our political ideals.

Finding answers to these questions, I think, should be of interest to those legal or economic scholars of a libertarian persuasion that like to look to history for possible models worth taking inspiration from.⁹

Notes:

- Roderick T. Long, “Anarchy in the U.K.: The English Experience with Private Protection,” Formulations Vol. II, No. 1 (Autumn 1994): pp. 9-10.

- Joseph R. Peden, “Property Rights in Celtic Irish Law,” Journal of Libertarian Studies Vol. I, No. 2 (1977): pp. 81–95.

- Terry L. Anderson and Peter J. Hill, The Not So Wild, Wild West: Property Rights on the Frontier. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press (2004).

- David D. Friedman, “Private Creation and Enforcement of Law – A Historical Case,” Journal of Legal Studies 8 (March 1979): pp. 399–415.

Friedman has also recently written a book going over disparate legal systems throughout world history, Legal Systems Very Different From Ours (2019). Possibly a work similar to that could be a relevant avenue for libertarian inquiry into the object of this article. - Fryslân in West Frisian.

- I say “The English language family” as I’m including Scots here as well, which of course would be the closest living relative to modern English, having branched off of Middle English; whereas at any rate English and Frisian diverged much earlier.

- Most of what I assert in this article has been freely taken from the Wikipedia entries on ‘Frisia,’ ‘Frisian Freedom’ and ‘Frisians’ [accessed November 7, 2022]. Again, none of what I’m saying here is meant to be novel so much as a means of piquing interest and a “call to attention” to something I think has received a frankly puzzling lack of it given aforementioned trends.

- After all, presumably libertarians qua libertarians would be intrigued by a region where a form of involuntary servitude ubiquitous throughout most of the continent allegedly held no presence.

- The only complication I will note is that a lot of the present literature will be written in Dutch or German, so some proficiency in one or both languages will likely be a requirement.