A thirteen-year old student recently told me that his parents weren’t speaking with his uncle because the uncle had voted for Trump. It’s not an unusual scenario. The choice of presidential candidate may just be the most culturally contentious decision that Americans make. It causes fights, break ups, public scenes, and (of course) Facebook blocks. We all know someone who, every four years, either on social media or in person, implores us (for the sake of humanity!) to vote Democrat. We all know someone ready to blame the coming apocalypse on us if we don’t vote Republican. We’ve all been tugged at by the idealistic third party voter. Some of us may even know a radical anarchist type who argues every four years that voting is immoral and sustains the war machine.

All these types share a common assumption: that voting matters. Indeed, the typical Democrat or Republican won’t be as offended by a vote for the opposite side as by the choice to not vote at all. Whatever the stripe, on one matter there is a near unanimous consensus: the choice whether to vote or not is a serious and important ethical question.

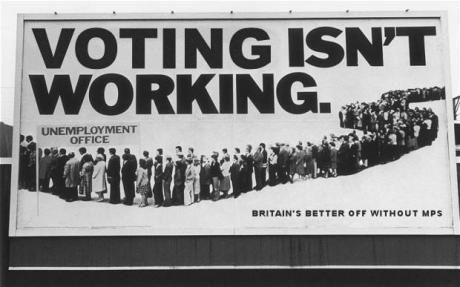

This mass assumption misses an incredibly simple and incontrovertible fact: voting does literally nothing at all.

One vote is one vote

Let’s get the obvious case out of the way first. If you don’t live in a handful of key swing states, your vote will drown in the mass of your state’s consensus. Hardly anyone disagrees with this.

But the truth is, even if you live in Ohio or Florida, your choice to vote or not vote will never decide the election. Your vote is just that – one vote. No state has come down to one vote. Ever. Given the population of the U.S., one vote deciding an election is a statistical near-impossibility. The 537 vote difference that tipped Florida and won Bush the election in 2000 is irrelevant. That was 537 votes, not one. If one non-voter had voted, the outcome of the Florida election would have remained the same.

What about third-party candidates, or write-in candidates? Even if they can’t win, shouldn’t we vote for them to get their numbers up even a little, and that way make them more visible to the general public? This misses the point. Let’s say – generously – that voting percentages get reported down to the hundredth of a percent. What are the chances that your one vote will bring your favored Green or Libertarian candidate up a hundredth of a percent? They are higher than the chances of deciding the election, of course. But even if your vote was the deciding vote, how much of a difference does that hundredth of a percent make? Is there any scenario in which it makes enough of a difference to render voting a rational act for someone despite how insanely unlikely s/he would be to cast the deciding vote?

The question of whether or not someone should do anything depends on three factors: what the desired outcome of the action is, the cost of taking the action, and the likelihood that the action will yield the desired result. When that last factor is astronomically tiny, the action always becomes irrational. It’s possible that by walking across the street at 4:02PM, you’ll have $200 fall out of the sky into your hand. But it’s so incredibly unlikely, that you would never consider going out of your way to do it, no matter how much you need $200, or how little out of your way it would be.

A classic retort to this argument runs as follows: “if everyone thought this way, then no one would vote and democracy would fall apart!” Let’s put aside whether everyone staying home on election day might not be a good thing. It is important to remember that when someone asks you to vote, they are asking for your individual vote. And your vote is only one vote. It is not everyone else’s vote, nor is it a magic wand that makes everyone else vote if you vote. What would happen “if everyone thought this way” is simply irrelevant to the question of whether you should vote or not.

Granted, convincing a lot of people to vote could sway an election; but this does not make any difference to the fact that as an individual, voting does absolutely nothing.

What about other mass actions?

It might seem like there’s something wrong here. All mass action – voting, yes, but also protests, boycotts, and even initiatives to keep litter off our streets – requires individuals to contribute incrementally to a cumulative result. For each individual participant in these mass actions, if that participant were not there, the cumulative result would be the same. Does this mean that if all people acted rationally, there would never be any mass actions?

There’s an important difference between voting and the other cumulative actions: the threshold. Voting is all or nothing. The result is exactly the same whether you vote or don’t vote, so long as the election doesn’t come down to one vote. In a protest, on the other hand, your presence makes a difference, however small. The protest, because it is not all or nothing, is sensitive to each small addition. If one person that is there weren’t there, the protest would be one person smaller, and that would make some tiny difference to the size of the demonstration. The protester can also magnify his/her impact by the way he/she protests (e.g. by punching a Nazi on camera). In the case of voting, if one voter didn’t vote, the same election outcome would result.

Of course, there’s some difference between a candidate who wins by 1% and a candidate who wins by 17%: the latter enters office with a so-called mandate. However, a threshold remains in the way election results are reported. Rarely will the difference between 17% and 16% – or even 17.41% and 17.42% – come down to one vote. And these are the numbers people typically see and remember. This stands in contrast with a protest, in which every single person makes the protest just a little bit bigger.

This question is ultimately one of scale. In small, local regions, one person might not be that unlikely to make the difference of one percent in the election report, and thus might have a chance to make a tiny difference in the mandate; and, in very large protests, one person might make such a small difference that she might be altogether negligible to the practical impact of the protest.

The all-or-nothing nature of voting makes it – in cases of comparable scale – significantly more irrational than other cumulative actions. This is supported by the fact that other types of cumulative action allow for ways to magnify individual impact. However, generally speaking, the larger any mass action is, the less likely each individual’s participation is to make any difference at all. Participating in a tremendously large protest is, for the most part, also doing something that in fact does nothing at all.

Significance

So why does this matter? Why don’t I let people waste a Tuesday afternoon in peace?

Unlike voting itself, the mistaken belief that “every vote counts” has serious repercussions. It makes people unwittingly powerless. It encourages them to focus their energies and priorities on an act that literally does nothing at all; they then leave satisfied, feeling that they’ve done their part and put in their contribution. It is counter-productive for activists to convince people that by doing something that actually does nothing, they’ve done something. The status-quo counts on this self-delusion to pacify us.

The problem isn’t with voting itself. Again, voting doesn’t do anything, including anything bad. By all means, go for it, I’m sure it feels satisfying for some people. The problem comes down to what we don’t do because we feel that by voting we’ve done our part. I know someone who spent hours of bureaucratic hell to vote in Florida instead of New York, because he felt he owed it to his community to make his vote count. He otherwise does little to nothing to take personal responsibility for the wellbeing of this same community. What might this person do if he realized that his vote is insignificant?

The perceived importance of voting encourages this complacency. Indeed, one of the institutional functions of voting is to cultivate this kind of passivity on a mass scale.

This is our society, and it is ours to govern. There are a million and a half ways of impacting change – ways in which each individual contribution is integral and unique. The notion that governing our lives is as impersonal and mechanical as pulling a lever locked between two choices is a delusion. This delusion deters us from discovering how each individual can creatively and uniquely generate society.