Some time ago, in a Facebook argument, I encountered someone who repeated the old “exchange of unequals” argument (i.e., that people never exchange equivalents because each party values what they got more than what they traded for it). I responded that this argument confuses exchange value with use value and that, regardless of subjective valuation, goods and services are viewed as having an exchange value equivalent to the price they fetch in a given market. This drew in a third person who said that exchange value is determined by use value, and that “experts on economics” had “proved” this. Making the mistake of continuing to argue, I said that there is no such thing as a generic “economic expert” because there were multiple contending schools of economics, many of which — the institutionalist school, in particular — had criticized the underlying assumptions of the marginalist economics he appealed to as an authority; I added that there was no such thing as “true” or “false” economics because economic theories were paradigms that could only be more useful for describing some sets of phenomena, and less so for others. My original interlocutor came back to say that, yes, there were schools of “pseudo-economics,” but they could be judged on their truth or falsity based on whether their conceptual tools were correct for evaluating real-world phenomena. I simply replied that the criterion he stated was the very basis upon which heterodox economic schools had criticized marginalism, and left it at that.

So I had an experience of deja vu upon reading an article at FEE (“Responding to Reich, Part 1: Is Economics Objective?” June 6) by Patrick Carroll. The article starts out on a bad foot, saying that Robert Reich is “arguably one of the most fervent anti-capitalists of our day. A prolific commentator, he is one of the chief proponents of left-wing economics, focusing on issues like inequality, Medicare for All, and the labor movement.” Yep (eyeroll), if talking about things like inequality and the labor movement doesn’t qualify as anti-capitalist, I don’t know what would.

Sarcasm aside, Reich is a garden variety liberal who wants to restore the New Deal or Postwar Consensus version of capitalism. That model is very much capitalist indeed. Capitalists, not socialist ideologues or idealists, played the primary role in designing it, out of their own capitalist interests. But I can see how Reich would raise the hackles of someone like Carroll, by denying that there are such things as generic “free markets”; there are only various alternative models of free market, whose different ways of functioning depend on the underlying institutional structure.

But let’s get to the meat of Carroll’s argument, such as it is.

There is an objective science of economics that is universally true, and we know this because we’ve been able to identify universally valid economic laws, such as the law of diminishing marginal utility, the law of returns, and the law of comparative advantage.

No matter what values we bring to the table, these laws don’t change and can’t be violated, just like the laws of geometry or logic. That means there’s something objective here, something that’s just true about the cosmos regardless of our opinions about right and wrong.

He goes on to quote Mises, from Human Action:

The teachings of praxeology [the study of action, of which economics is a subdiscipline] and economics are valid for every human action without regard to its underlying motives, causes, and goals… In this sense we speak of the subjectivism of the general science of human action. It takes the ultimate ends chosen by acting man as data, it is entirely neutral with regard to them, and it refrains from passing any value judgments. The only standard which it applies is whether or not the means chosen are fit for the attainment of the ends aimed at.

…It is in this subjectivism that the objectivity of our science lies. Because it is subjectivistic and takes the value judgments of acting man as ultimate data not open to any further critical examination, it is itself above all strife of parties and factions, it is indifferent to the conflicts of all schools of dogmatism and ethical doctrines, it is free from valuations and preconceived ideas and judgments, it is universally valid and absolutely and plainly human.

Yes, neoclassical/marginalist economics — and the Austrian economics to which Carroll predictably adheres — is technically “objective” in the sense that it’s a set of rules that objectively produce the same results from a given set of inputs every time. But the axioms of Austrian economics are, in themselves, trivially — or even circularly — true. What matters is the application of those axioms in a manner sufficiently sophisticated to generate meaningful statements about complex economic phenomena. The assumptions governing that application, and even what questions to ask, reflect value judgments. Any economic paradigm involves such choices, and the choices made will render it more relevant for some purposes and less relevant for others. Those choices are unavoidably political.

Right-libertarian adherents of Austrian economics constantly show themselves incapable of the sort of critical thinking required to apply their rules. Mises himself, in Epistemological Problems of Economics, wrote: “If a contradiction appears between a theory and experience, we must always assume that a condition pre-supposed by the theory was not present, or else there is some error in our observation.” Most of his disciples — at least those who write op-eds of the sort that appear at FEE — fail to even perceive such questions of application as an issue. They blithely make generalizations like “Minimum wage increases cause unemployment,” or “wages are determined by marginal productivity of labor” — such generalizations being the “economics” they usually have in mind when they smugly tell others to “Learn some economics!” — without for a moment stopping to consider such ceteris paribus qualifications as elasticity of demand, or the possible existence of unaccounted-for factors which might explain the failure of wages to match increases in labor productivity over the past fifty years.

They will boldly proclaim that Jevons, or Menger, or Böhm-Bawerk, “proved” that exchange value is determined by subjective utility — ignoring the fact that this is only true, in the ordinary sense of those terms, under the highly artificial conditions of the spot market, with quantities supplied and demanded fixed at the point of exchange. Once time is factored in, and we’re dealing with a dynamic model in which supply and demand changes over time, the statement is true only in technical and specialized senses of the terms used. At any given time, goods will sell at a price that reflects marginal utility. But if there are disappointed sellers or disappointed buyers left over, as in Böhm-Bawerk’s “marginal pairs” thought experiment, the quantity demanded or supplied will shift over time until — if demand and supply are both elastic — the marginal utility itself reflects production cost. In other words, we’re back to the classical political economists’ law of cost.

But instead of treating marginal utility as complementary to classical political economy — i.e., as a more sophisticated mechanism for explaining the law of cost — by and large the marginalists have welcomed it as a way of obscuring the practical insights of classical political economy. As James Buchanan described the situation, Ricardian political economy had as its general paradigm a cost theory for goods in elastic supply, with a special theory — based instead on subjective utility — for goods in inelastic supply (e.g. works of art or food in a city under siege). Marginal utility, according to Buchanan, applied the special paradigm to all goods, treating them all as in fixed supply at the immediate point of exchange — thereby conveniently obscuring the law of cost.

Marginalism as a paradigm, more broadly, conveniently obscures many other practical — and potentially radicalizing — observations of classical political economy. For example, time preference is a gratifyingly neutral-sounding explanation for profit; it serves essentially the same apologetic purpose as earlier doctrines like “waiting,” “abstention,” or the “wage fund,” and is commonly trotted out by right-libertarian polemicists for just that purpose. But on closer examination, the steepness of time preference — one’s relative inability to wait for payment — correlates to poverty and precarity. As I pointed out here, Böhm-Bawerk himself admitted as much in The Positive Theory of Capital:

He conceded that it was possible that the random fluctuations of the market would, from time, reduce the number of competing property owners, lenders, or employers relative to borrowers or employees. The combination of “monopolising of property” and “compulsion on the poor” would steepen the time preference of the latter, so that the rate of interest would momentarily increase. Even more telling, he continued: “…the very unequal conditions of wealth in our modern communities brings us unpleasantly near the danger of exploitation and of usurious rates of interest.

What he treated as a hypothetical was in fact the previous three or four hundred years of the actual history of capitalism. “Time preference” amounts to a nice way of saying “how bad we’ve got you over the barrel” — if it means anything at all, it’s simply a more theoretically elegant way of restating older observations about structural inequality and differentials in bargaining power.

Likewise, the defense of the sizes of the respective revenue streams going to the various “factors of production” in terms of their “marginal productivity.” Marginal productivity is simply what a given factor input adds to the exchange value of the finished good. That means that whatever the “owner” of a “factor” is able to charge for it, translates precisely into its “marginal productivity.” So marginal productivity is determined by the relative power of the owners of the various factors of production. And marginal productivity theory is a way of sweeping actual considerations of class and institutional power under the rug, redefining them in terms of ostensibly “neutral” and “objective” laws of distribution.

What Carroll calls a “free market” — a system in which market-clearing prices are free to form — is compatible with a wide number of possible sets of institutional frameworks, property ownership rules and property distributions. Contrary to the standard polemics of the libertarian right, no one particular set of such frameworks and rule sets is self-evidently deducible from self-ownership and non-aggression. And the particular property rules central to the capitalist era did not arise spontaneously, Lockean narratives aside, from “voluntary homesteading” and the “propensity to truck and barter” — far from it. But every one of those different possible institutional frameworks and property rulesets will result in widely different values for supply and demand, and hence in widely different prices and distributions of the product among institutional actors.

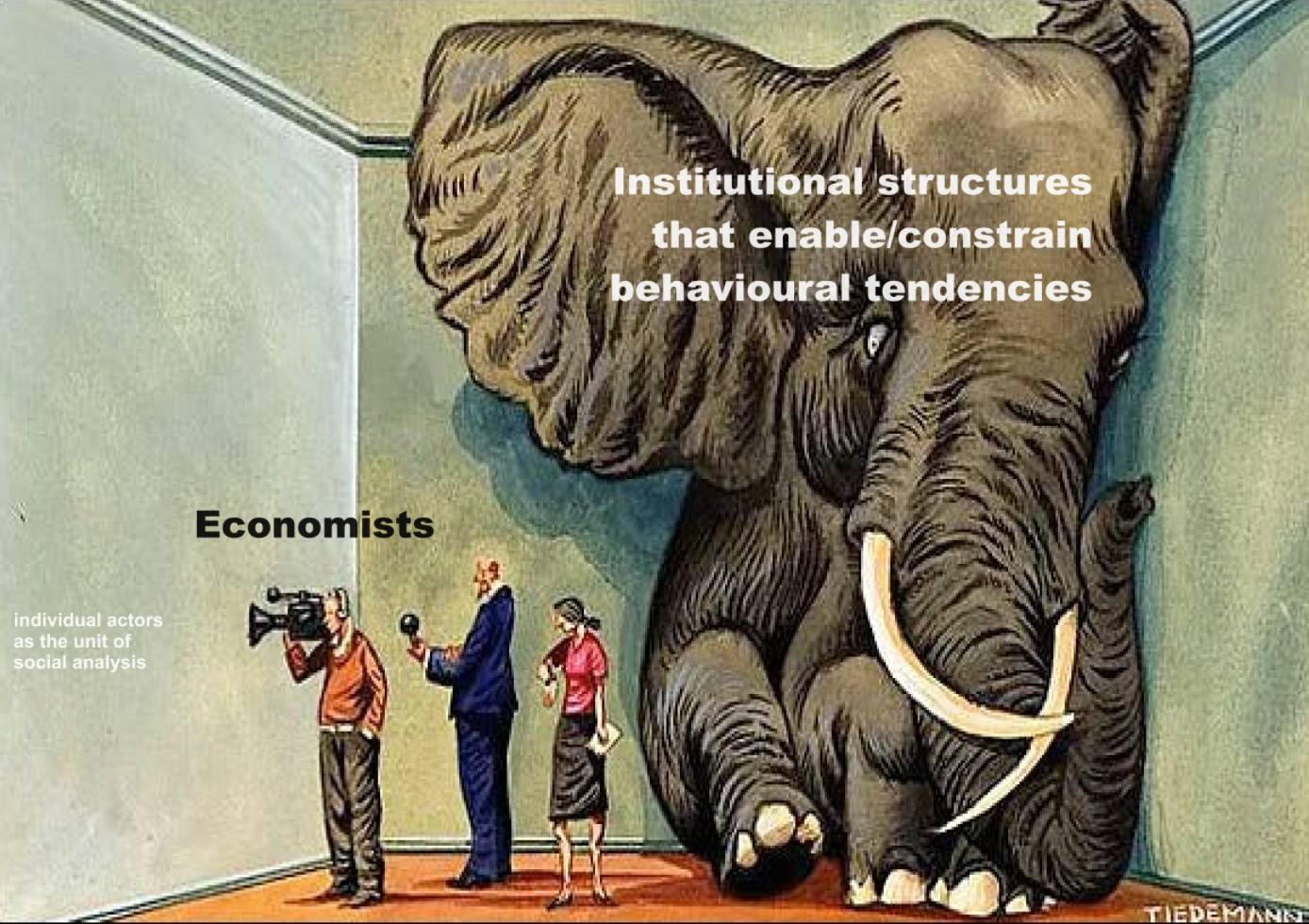

So, as the cartoon above (courtesy of Sirbucktea Undreiyas on Facebook) suggests, the “objective economics” Carroll touts attains its formally valid character by stripping away all context of property rules, power structures, etc. But its concepts are largely meaningless in any practical sense, without taking such contexts into consideration. Heterodox economic thinkers, from the institutionalists Thorstein Veblen and John R. Commons to the Marxist Maurice Dobb, have pointed out the power blindness and resulting theoretical irrelevance of marginalist economics — a subject I covered at length here.

In other words, Carroll’s “objective economics,” to the extent that it is objective, is trivial or circular and largely useless. It ignores — or provides disingenuous and misleading answers to — all the questions that are worth asking.