[Originally published as Intimidation at Customs — ed.]

I recently traveled to South America with my family and crossed the borders of a few nations in the process. At every step of these transitions I felt like a sheep, my heels nipped by bureaucratic sheep dogs. I didn’t have anything to hide, but the stress of encountering the border watchers was alternatively instructive, expensive, and nerve-wracking.

My first border experience of the trip was at the Lima airport in Peru. They did not ask many questions about what was being brought into or taken out of the country like they do at American customs, but one had to pay the “tarifa aeropuerto” in a separate line before going through security. I encountered the same thing at the airport in Cuzco. Most other airports, Argentina included, have the airport tax built into the ticket price. In this way, I liked that the Peruvian government reminded me so overtly that I’d have to pay them $70 for every international flight in or out of the airport and $30 for each domestic flight rather than using subterfuge to sneak it in my ticket price. If all taxes were collected in this manner there would be a minarchist state wherever enacted in about twenty minutes.

Outside of the airports, we luckily rubbed up against the local authorities only once. We hired a tour guide to show us around Lima one day. South of Lima near the archaeological site we were visiting, Pachacamac, our guide didn’t have her seat belt on. We got flagged over by a cop on the side of the road, though I seriously doubt he was able to see that she did not have a seat belt on. Either way, our driver sycophantically hopped out of the car with his papers and hat in hand and greased the wheels of justice with a $20 tip. In return, we escaped with our freedom.

Later in the trip, one of our hosts in Argentina, a family friend, told me a story about how he used to drive the infamous Volkswagen automobile dubbed, “The Thing.” This cheap car, in his recollection, had almost no bells or whistles, especially in the safety department. He stated that at least three times during his ownership he was driving to school and was pulled over by cops who knew the Thing didn’t meet safety requirements and was solicited for a bribe. They knew, because it was a cheap car, that while he may not be able to afford a ticket or a safer car he would be willing to pay a less expensive bribe. They were right.

I can at least admire these sorts of shenanigans because they are honest. They don’t allow the doublethink we have in America where one is socially pressured into being grateful for the defense services one is forced to pay for by virtue of geography. These sorts of interactions show the citizen/police officer relationship as more thoroughly and openly adversarial than the one I’ve experienced back home, where it is rather muddled. Though I have certainly faced the unease and fright of bearing the scrutiny of an armed mustached man in costume, I have never been asked for a bribe, especially not for any miniscule traffic violation which would only hurt the passengers of the car they voluntarily chose to drive. With such widespread and open corruption, it is nice to see some native skepticism and doubts on the honor of the watchers.

Conversely, another one of our hosts told me that the police randomly pull over people in Argentina without probable cause, but he reassured me that if one wasn’t doing anything wrong one should have nothing to fear. I tried explaining the American skepticism and cautiousness toward the authority given to law enforcement. I illustrated that this principle is inscribed in the Constitution and many Americans (though not nearly enough of them) are concerned with flexing their rights during police encounters. Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? didn’t make much of an impression on this Argentine. I got the impression that he thought that rights that protect citizens from police abuse do more to impede just police activity than to help regular people avoid injustice.

Thankfully, the ex-owner of the VW Thing took me out to a local watering hole one night with some of his friends. They explained to me that there is lingering resentment toward the military in Argentina due to the numerous military coups they had staged in recent Argentine history. Perhaps my conclusion from these stories and experiences isn’t that of Argentine blind faith in authority figures or of universal skeptical resentment of them, but it is a mixture of both attitudes, much like my home in the United States. There are those with a Hank Hill-esque trust of the police but also those who rightly fear the police and military as much or more than they fear criminals who are not endorsed by the state.

When I left Peru to fly to Buenos Aires, there was a big sign at customs declaring a “Reciprocal Fee.” A few years ago the United States government declared that visitors from Argentina had to pay a sizable visa fee to enter America. Argentina retaliated with the same tax of $131 which began in January of 2010. It is about as arbitrary as any other government shakedown.

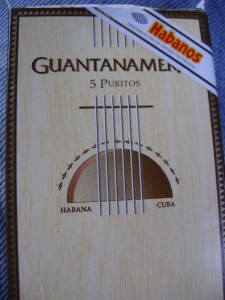

Also in the vein of annoying and pricey barriers to the movement of free and peaceful individuals, one of the first things I did in Argentina was buy some duty-free Cuban cigars. Their delicious reputation is well known in America, epitomized by the story of President John F. Kennedy acquiring a huge stash of Petit Upmanns for himself before the embargo of Cuba commenced. I took advantage of the quasi-untaxed nature of duty free cigars, which barring limits on the amount of goods one can transport, is a relative libertarian gala.

On my return flight to America I anxiously fingered the cigars in my jacket pocket, but ending up leaving them on the plane in the international zone before encountering the American customs officials. Coming back through customs at Los Angeles International Airport was pretty stressful, even though I had nothing on me to merit such apprehension. There I was asked questions about where I went, who I knew in South America, why I went, whether it was my first time, what I brought back, what I studied at university, etc. One definitely gets the sense that one is a criminal in this unavoidable and Constitutional rights-free exchange. I looked my interlocutor in the eye, answered his questions, and they let me go after a few minutes without too much trouble. I wonder if I would have been able to keep my cool with, GASP, a few measly cigars.

I half-seriously toyed with the idea that Groucho Marx, in a previous epoch, had humorously gone through American customs and listed his occupation as ‘smuggler.’ Seeking to avoid feeling the fist of state power inside my nether regions for the benefit of a joke, it was not to be.

My reflections about my border crossing experiences and observations of the police in Peru and Argentina are deeply shaded by my libertarian values. I understood these encounters to be less about ‘protecting the country,’ and more about instilling a deep sense of intimidation in all those who have the misfortune of an encounter with the business end of the law. And bad news, it works. Rather than international travel being a celebration of the free movement, trade, and communication of liberated humanity, these positive aspects are often dwarfed by the corruption and fear that statism produces everywhere it reigns.