Even if you’ve never read a comic book or seen a superhero movie, Stan Lee has affected your life. His storytelling. His approach to heroism. His moral lessons. His ethos, embodied in the catchphrase “Excelsior!” The Mount Rushmore of modern pop culture surely has a spot for him. His imagination permeates humanity’s modern collective imagination. Through the countless worlds and characters he brought to life, Stan Lee will live on longer than most of us.

Younger people mostly know Stan Lee from his unforgettable, 18-year string of cameos in Marvel films, especially the MCU. Sadly and poetically, his likely final cameo is already filmed for the upcoming untitled Avengers film, which is the finale to the MCU’s Three Phase, 22-movie, 11-year saga. My own early memories of Stan Lee come from the 90s Marvel cartoons: “Fantastic Four,” where “Mr. Marvel” himself would enthusiastically introduce each episode to the viewer, and “Spider-Man,” where our hero meets the real Stan Lee in a cross-dimension finale, equal parts heartfelt and meta.

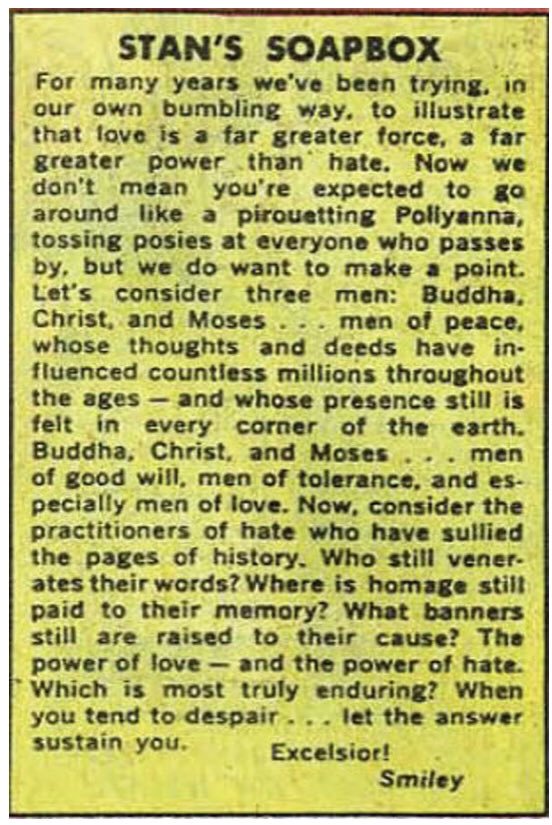

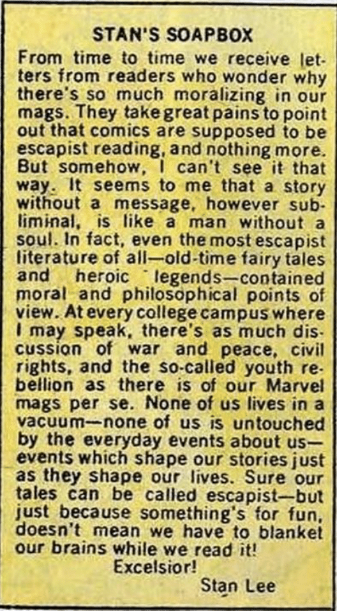

First-Generation Marvel fans surely remember Stan Lee from the 60s comics bookended by his exuberant introductions and editorial columns, as well as the broader “superhero spokesman” public persona he developed at conventions and college campuses (no doubt helping to salvage a comics industry plagued by PR troubles and government censorship in the 50s).

If you’re here to learn about Stan Lee’s life as a comics writer, especially his complex legacy with his creative collaborators (after all, comics are primarily a visual art form), I strongly recommend you read the informative and respectful obituaries written by Spencer Ackerman and Jeet Heer. It would be unjust and ahistorical to fail to note how Lee’s artists (particularly Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko) were just as much, if not more, central to Marvel’s legacy and that Lee ultimately added the dialogue and written ideas onto their drawings and visual ideas.

While I don’t think the contributions of the artist and the writer can be totally disentangled in a meaningful way, I do think it’s mostly Stan Lee as the editor who seemed to guide the broad philosophy and ethos of 60s Marvel storytelling. This influence shows across all the artists (and is then articulated it in the characters’ thoughts and words), and it was Stan Lee’s contributions that made the most lasting changes to superheroes.

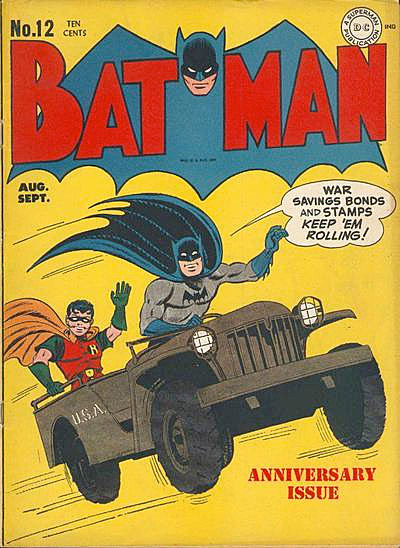

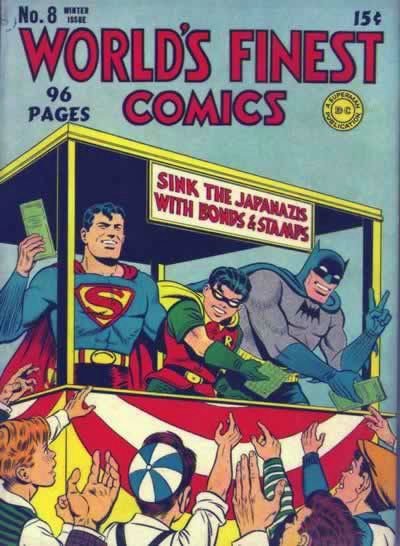

It’s hard to overstate how revolutionary Marvel’s 60s lineup — Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, Thor, Iron Man, the Hulk, Black Panther, Doctor Strange, etc. — was for the superhero genre. Before, superheroes were more like parental figures, buff cardboard cut-outs without much real human personality or individuality. Side-kicks like Robin were created so the young readers could identify with someone, while Batman could tell them what to do, how to act, who to respect, and when to buy war bonds.

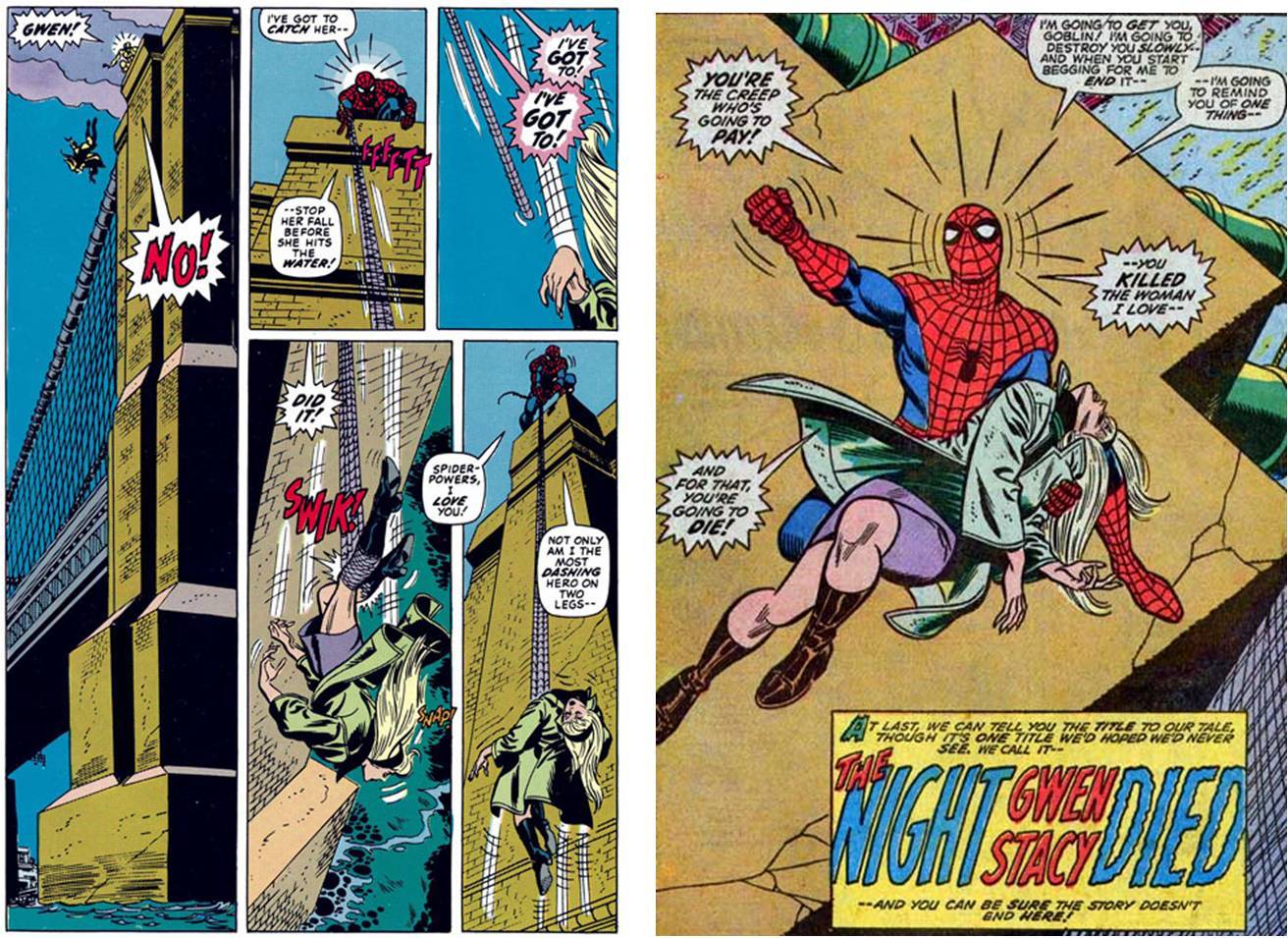

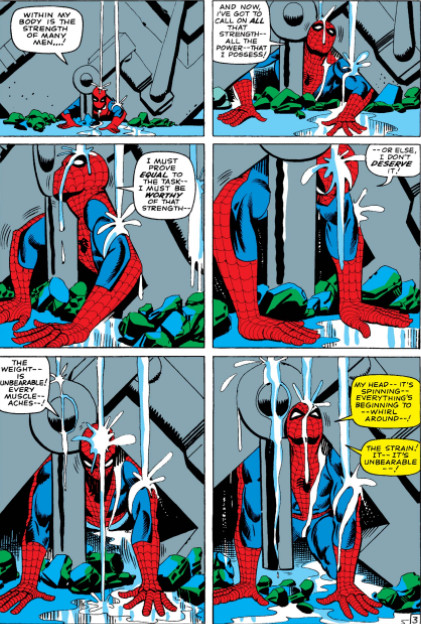

But in 1962, Stan Lee and Steve Ditko created Spider-Man in direct subversion of the side-kick trope. Now, the side-kick was the superhero. Young readers no longer imagined themselves fighting alongside, and taking orders from, the superhero. Instead, the reader was the superhero. The superhero’s struggles were their struggles. The superhero’s world was their world. The superhero’s moral quandaries were their moral quandaries. Lee pushed for Spider-Man to be an ordinary teenager first, and superhero second. Likewise, the Fantastic Four was an ordinary family first, and superhero team second (*cough* Guardians of the Galaxy *cough*). And the Hulk was a guy with anger issues first, and superhero…barely ever.

By subverting the genre expectations set up by their Golden Age predecessors, Lee, Ditko, Kirby, and company brought superheroes down to Earth in the Silver Age. They made them relatable, vulnerable, flesh-and-blood people with whom we could identify and learn from, not through obediently taking orders, but through sharing their experiences, using our empathy, and achieving an emotional catharsis. Superheroes were transformed from two-dimensional mouthpieces for authority into three-dimensional weirdos, teenagers, and outcasts. Their stories were transformed from unabashed wish-fulfillment escapism into something that more closely resembled the real world, including its strife and failure.

Aristotle was basically right that art can help us expand our understanding and reflect on our own life. By stepping outside our ordinary perspective and experiencing things through the eyes of fictional characters, we can discover things about both the world and ourselves. Aristotle placed moral learning at the center of his ethical theory, which is why he heavily emphasized the importance of tragedy in his writings on aesthetics. As creatures of both imagination and habit, art can dispose us to act more virtuously or more viciously. And through tragic art, we learn moral lessons central to the human condition; lessons about perseverance, loss, triumph, fear, acceptance, power, and responsibility. Using the comic book medium and the superhero genre to teach these lessons is one of the most aesthetically important and influential pop culture innovations of the last 100 years.

Where the comics creators of the 30s and 40s seemed to agree more with the views expounded in Plato’s Republic, that art was intellectually impotent and morally shallow, Stan Lee sided with Aristotle. What now seems like an obviously perfect fit — especially since the superhero genre was sparked by the Hercules-inspired Superman and infused with the epic heroism of Ancient Greek and Roman mythology ever since — was groundbreaking. By applying Aristotle’s ancient insights to the superhero genre, Stan Lee changed the world. Now, young readers were able to relate to, and learn deep insights from, their heroes. After their Aristotelian turn, superheroes reached a new echelon in American pop culture. Slowly but surely, they went from cheap pulp rags to modern folklore.

Shared art can shed light on a culture and how its people think about the events that shape them, process collective trauma, and (hopefully) achieve collective catharsis. During “Hollywood’s Golden Age,” not coincidentally coinciding with the Great Depression and World War 2, people found comfort in escapist films: mostly adventure, romance, comedy, cartoons, and propagandistic war movies, populated by larger than life heroes like Robin Hood and Rick Blaine. But by the time of the counterculture and Civil Rights movements of the 60s and 70s, the “New Hollywood” style took over in response to the need for a different kind of collective catharsis. Audiences wanted realistic violence, risque sex, up-close criminality, and the brutality of war presented in movies populated by grounded and relatable heroes like Bonnie and Clyde or Easy Rider’s freewheeling stoner motorcyclists, Wyatt and Billy.

Like Hollywood’s Golden Age, the Golden Age of Comics — which spawned Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and Captain America — let depression and wartime audiences escape into stories of wish fulfillment. If Rick Blaine joining the war effort was the great wartime hero, surely the great wartime superhero was Captain America, fulfilling the wish of toppling Hitler with a single punch. Historically a medium for young people, comics avoided the dark grittiness of 60s movies. But like filmgoers, comics-readers during the era of counterculture and civil rights demanded more grounded heroes and stories with more substance. Stan Lee recognized that and infused the Marvel Universe with the perfect balance of moralizing and escapism, message and story, philosophy and legend.

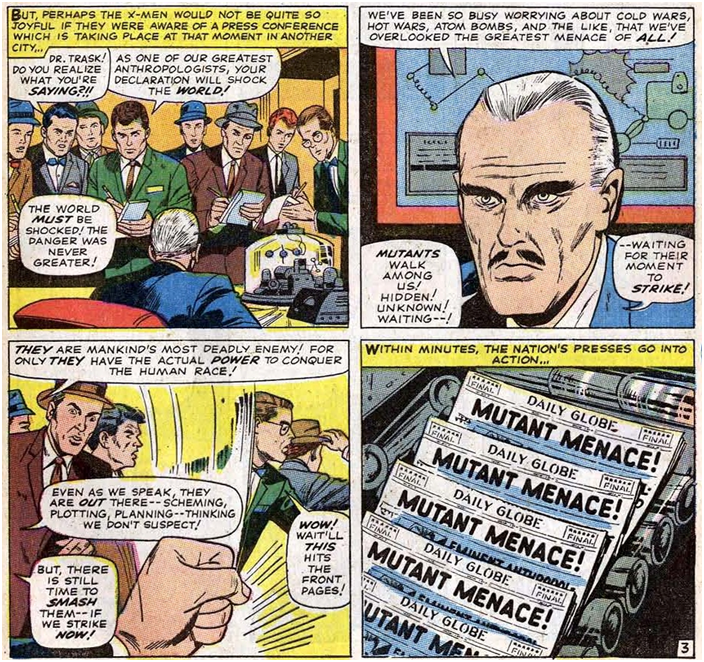

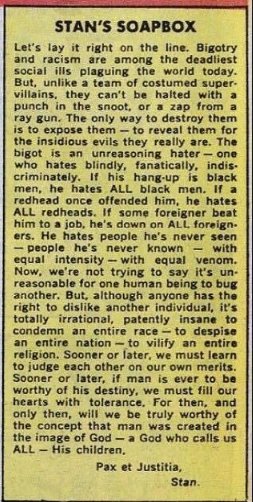

Lee, Kirby, Ditko and company envisioned the fantasy and sci-fi elements of the superhero genre as vehicles to explore more substantive issues through symbolism, subtext, and melodrama. Mutants were victims of bigotry and the X-Men sparred with the Brotherhood of Mutants over an ideological disagreement about when violence was justified in fighting oppression. The Fantastic Four’s abilities were metaphors for their psychological struggles and personas (Reed stretched himself too thin with work, Sue felt invisible, Johnny was a hothead, Ben felt like a monster). The Hulk was a part of Bruce Banner’s personality that he couldn’t control and which fed on his rage. Captain America, who was more of a Rick Blaine-style propagandistic hero when he was created in the 40s, was revived as a “man out of time” who eventually lost his patriotism. Marvel readers got to see real people talking about real issues.

I think the broad tonal and stylistic differences between the Greatest Generation’s superheroes and Gen X’s superheroes explains part of why the Marvel Cinematic Universe has consistently outdone the DC Extended Universe. While the influence of Silver Age Marvel was felt by the whole genre in due time, DC’s major characters — Superman, Batman, Green Lantern, Flash, Aquaman, Wonder Woman — still carry heavy stylistic and tonal baggage from their Golden Age origins in the form of more distant, unassailable personas and God-like qualities and worlds. Yes, the movie-makers matter. But certain characters and source material naturally gravitate towards certain kinds of stories and tones.

The MCU has brought to life a familiar world inhabited by unceasingly human characters — with all the heavy emotion and passion that sprung from Kirby’s and Ditko’s pencils and all the relatable and inspiring dialogue that sprung from Stan Lee’s pen. It’s no coincidence that the most highly praised aspect of the MCU is the casting (which makes up for the films’ defects, at least according to the box office). It is experiencing those very characters on the big screen that is the most joyful and wondrous part of it all.

It’s not surprising that when Hollywood was ready to combine good CGI with heavily-branded intellectual property, it’s the 60s Marvel Universe that would generate the biggest movies of all time and ascend to a sort of post-9/11 American secular mythology. Indeed, Stan’s characters have much to teach us about hope in the wake of tragedy and strength in the face of crisis. But they also have much to teach us about power and responsibility while the longest war in our history rages on. They can teach us about innocence and privacy while our civil liberties are trashed, and about love and acceptance while immigrants and minorities are scapegoated.

I don’t wish to imagine how dreary modern pop-culture would be absent the influence of Stan Lee and his unwavering trust in young readers, his confidence in the cathartic and educational potential of comic books, his passionate belief in the moral power of superheroes, his life-long lessons about the twin nature of power and responsibility, and his countless tales of love triumphing over hate. Our world is just as much a product of art as art is a product of our world. I owe much of my world to Stan Lee. The man that changed superheroes forever also changed people forever.