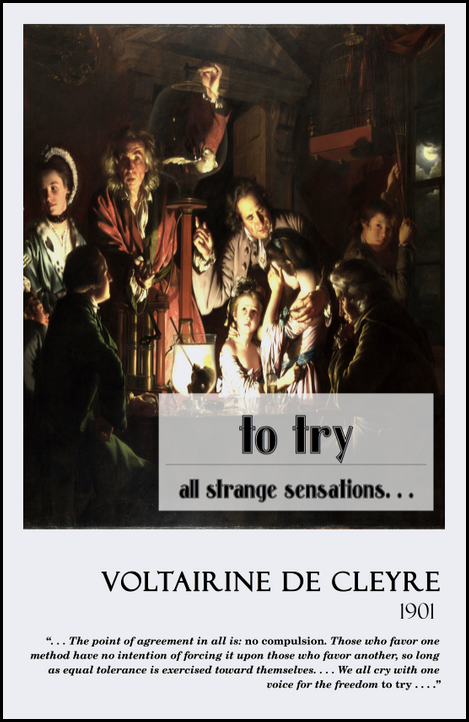

C4SS has teamed up with the Distro of the Libertarian Left. The Distro produces and distribute zines and booklets on anarchism, market anarchist theory, counter-economics, and other movements for liberation. For every copy of Voltairine de Cleyre’s “to try all strange sensations…” that you purchase through the Distro, C4SS will receive a percentage. Support C4SS with Voltairine de Cleyre’s “to try all strange sensations…“.

$1.50 for the first copy. $0.75 for every additional copy.

The essay reprinted in this booklet was originally published as “Anarchism,” in the October 13, 1901 edition of the Anarchist movement newspaper FREE SOCIETY (ed. Abe Isaak). I’ve retitled it because that’s a boring title for an essay about Anarchism in an Anarchist newspaper, or in an Anarchist pamphlet series.

But the content is anything but: A startling, provocative, and moving statement of de Cleyre’s emerging re-conception of anarchy herself as “an Anarchist, simply, without economic label attached,” — and of anarchy as a pluralistic process of social experimentation and self-exploration, — the essay has been retitled with two of the most striking phrases appearing in the text, speaking of the freedom “to try. . .” and of the anarchic, un-ruly self as a bottomless depth of “all strange sensations.”

“I have now presented the rough skeleton of four different economic schemes entertained by Anarchists. Remember that the point of agreement in all is: no compulsion. Those who favor one method have no intention of forcing it upon those who favor another, so long as equal tolerance is exercised toward themselves. . . . For myself, I believe that all these and many more could be advantageously tried in different localities; I would see the habits of the people express themselves in a free choice in every community; and I am sure that distinct envionments would call out distinct adaptations. My ideal would be a condition in which all natural resources would be forever free to all, and the worker individually able to produce for himself sufficient for all his vital needs, if he so chose, so that he need not govern his working or not working by the times and seasons of his fellows. I think that time may come; but it will only be through the development of the modes of production and the taste of the people. Meanwhile we all cry with one voice for the freedom to try. . . .”

“Are these all the aims of Anarchism? They are just the beginning. They outline what is demanded for the material producer. Immeasurably deeper, immeasurably higher, dips and soars the soul which has come out of its casement of custom and cowardice, and dared to claim its Self. Ah, once to stand unflinchingly on the brink of that dark gulf of passions and desires, once at last to send a bold, straight-driven gaze down into the volcanic Me, once, and in that once forever, to throw off the command to cover and flee from the knowledge of that abyss, — . . . to realize that one is. . . a bottomless, bottomless depth of all strange sensations . . . quakings and shudderings of love that drives to madness and will not be controlled, hungerings and meanings and sobbing that smite upon the inner ear . . . To look down into that, to know the blackness, the midnight, the dead ages in oneself, to feel the jungle and the beast within, . . . — to see, to know, to feel the uttermost, — and then to look at one’s fellow, sitting across from one in the street-car, . . . and to wonder what lies beneath that commonplace exterior — to picture the cavern in him which somewhere far below has a narrow gallery running into your own. . . . Letting oneself go free, go free beyond the bounds of what fear and custom call the ‘possible,’ — this too Anarchism may mean to you, if you dare to apply it so.”

Voltairine de Cleyre (1866-1912) was a popular Anarchist and feminist writer, speaker and activist. Her contemporary and friend Emma Goldman called her “the most gifted and brilliant anarchist woman America ever produced.” She published articles in Liberty, Twentieth Century, Free Society and Mother Earth, and worked closely with libertarian communists, market anarchists, and mutualists within the Philadelphia social anarchist movement, but refused to commit herself to economic blueprints, adopting a pluralistic view of economic arrangements in any future free society.