The following article was written by Friedrich von Blowhard and published on 2 Blowhards, February 16, 2007.

Friedrich von Blowhard writes:

As you know, I am a small businessman. As a result of what I do I spend time talking with investment bankers and bankruptcy lawyers. In the process I have learned a little (okay, very little) about finance. I want to talk about one of the concepts I stumbled across in finance that seems to make a lot of sense. That is the notion of a general and positive correlation between risk and reward. This is a pretty basic concept; the Wikipedia article on risk (which you can read here ) puts it this way:

A fundamental idea in finance is the relationship between risk and return. The greater the amount of risk that an investor is willing to take on, the greater the potential return. The reason for this is that investors need to be compensated for taking on additional risk.

This certainly resonated with my personal experience. As the owner of (and sole investor in) a small business, I had the potential to make more money than I had in a previous career as a salaried employee, but I had to take considerably more risk to get it. And this seems true of small businesses as a class. It appears from reasonably careful studies (such as those quoted in this story) that around half of all small businesses close in the first five years of operation. That implies a roughly a 13% annual failure rate. That number apparently rises to two-thirds in a decade, which would imply that in the second five years the failure rate drops to around 7% annually. Although the story implies, no doubt accurately, that some business closures are not complete crash-and-burns, I know from personal experience that the vast majority of such terminations are fraught with emotional and financial loses.

Pondering the notion that increased risk ought to imply increased reward, I was struck by the notion that society might see a lot more entrepreneurship if it adjusted income taxes for the downside risk associated with a given level of earnings. It seemed unfair to tax a small businessman who earned a $100,000 profit by betting his own money exactly as if he was collecting a $100,000 salary from an employer who was absorbing the associated downside risks. After all, if the skill or luck of a small businessman turns bad, he might make no money at all the next year, or more to the point, he might not just lose his livelihood, but his savings and his house as well. I can remember in my first decade in business the peculiar sensation of being required to personally guarantee the debts of my business, something I do not remember ever being required to do as an employee.

The Risk-Reward Curve and Its Outliers

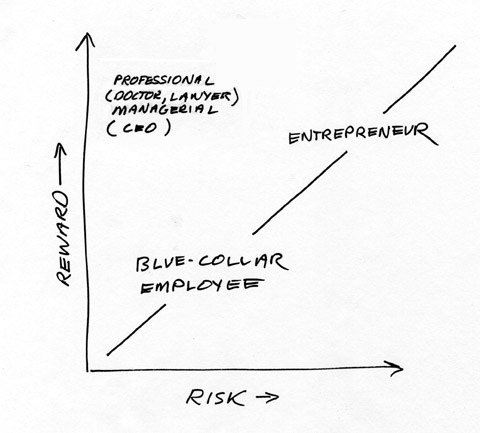

Playing with this notion, I even constructed a rough risk-reward curve for society as a whole. Well, the axes lacked numbers, but as I recall the same was true of the graphs in my college econ textbook.

After I sketched this out, it dawned on me that there were a number of professions that were way off the general curve. Doctors, lawyers, and accountants, for example, made a lot of money but did not have to put much money at risk to earn it. At least I never remembered seeing a single Going Out of Business Sale: Medical Supplies Cheap sign posted on any doors in the medical buildings I ever visited.

As the years went by, I saw an increasing number of stories in the newspaper about another group that was likewise off the standard risk-reward curve: corporate CEOs. I remember reading an article in the early 1990s on the then-rising trend of rewarding such executives with stock options in order to better align their interests with those of their stockholders. (This approach to compensation really took off in 1993 after the Clinton administration decided that CEO salaries in excess of $1 million would no longer be tax-deductible.)

I noticed a little flaw in the alignment between CEOs and stockholders that stock options were supposed to provide, however. If the stock of the corporation rose, the CEO made a killing, especially relative to the amount he had invested (i.e., nothing.). However, if the stock price fell, he or she did not lose a thing. Heads the CEO won big, tails the ordinary stockholder lost. I thought: why not lend the CEO money to buy stock in his or her corporation? If the purchased stock rose in value the CEO would make a lot, but if the stock lost value the CEO would lose his or her shirt, just like the ordinary shareholder. Then interests would really be aligned.

Oddly, none of the CEOs (or the members of their corporate compensation boards) seemed to find this obvious logic compelling.

And then more recently I started to notice a lot of stories about the stupendous compensation being collected by some hedge fund managers. I also noticed that this compensation seemed to work a lot like that of corporate CEOs, very good in good years, and with no particular downside in bad years. As this story points out, the trader whose ill-considered bet on natural gas prices cost investors in the Amaranth hedge fund some $5 billion last year was eventually sacked in disgrace. However, it probably softened the blow as the ex-trader sat at home watching TV and drinking beer in his underwear to remember that in 2005 he had earned $80 million.

To a small businessman bankrolling his own business, this sounds like going to Vegas with a group of rather simple-minded people who have agreed to make good your losses, but who have generously agreed to allow you to keep a big piece of any winnings. Yowsa!

So How Are Risk-Averse Professionals and Managers Doing?

Over time, I kept track of what was going on with the members of my pet risk-averse group of professionals and corporate/financial managers. I discovered that academics had given this group had a name, either The New Middle Class or, for brevity, The New Class. I also noticed that this group seemed to keep getting a better and better deal from our society. Doctors, of course, are big wheels in healthcare (and generally rake in around 20 cents on every additional healthcare dollar spent); as everyone knows, the healthcare sector has expanded over the past 40 years from a puny 5% of the 1965 economy to over 15% of the much, much larger economy 2007 economy. (If you have been deceived by the hype that managed care has crushed doctor earnings, you might check out this summary of what doctors earn.)

According to the American Lawyer, it appears that the largest law firms have been increasing their billings at a clip of roughly 10% a year in an economy that is not growing at remotely that rate. According to this story, average partner compensation at these firms was almost $1 million annually as far back as 2004, a number that has no doubt since been exceeded.

As for CEOs of public companies, this story in the Christian Science Monitor points out that while in 1980 CEO compensation was a measly 41 times the pay of the average worker, in 2003 CEOs were taking home 500 times the pay of the average worker. Again, I am not aware that the last 4 years have seen this trend reverse itself.

And as for hedge funds, according to this story from Reuters, assets managed by hedge funds increased 29% in 2006, hitting $1.43 trillion dollars. (BTW, this number almost certainly includes some of your pension fund money, whether you know it or not.) Since hedge fund managers are paid (among other ways) on a percentage of assets under their management, well, they are obviously doing even better than they were in 2005.

But no doubt my group of highly rewarded yet risk-free experts and managers, the best and the brightest of our society, use their great brains to realize remarkable results for the rest of us, right? I mean, without the genius of the current crop of admittedly highly compensated CEOs, public company profits and shareholder returns would be in the toilet, right?

Well, maybe not. I happened to read a 2005 paper by Ian Dew-Becker and Robert J. Gordon of Northwestern University, Where did the Productivity Growth Go? Inflation Dynamics and the Distribution of Income. (You can peruse this paper here (PDF)). In it I saw some data that suggests that our highly compensated CEOs are not doing as well by their shareholders as their more poorly compensated predecessors 50 years ago did:

[I]t is immediately clear from Figure 3 that the share of before-tax corporate profits declined from about 13 percent of domestic income in 1950 to about 11 percent in [the first quarter of 2005.] These profit shares place some perspective on recent debates about whether productivity gains have gone disproportionately to [shareholders. In fact,] there has been a long-term decline in the profit share. [emphasis added]

And as for the results that investors have realized at the hands of hedge-fund managers, well, here is what The Economist had to say in the November 18th-24th 2006 edition (I was unable to find a copy of this online, at least for free):

The trouble is that hedge-fund managers are not producing the kind of bonanza they used to in the days when George Soros, the man who famously broke the Bank of England on Black Wednesday in 1992, dominated the sector. In the 1990s, their compound annual return was 18.3%; since 2000, it has been just 7.5%…This creates a problem for investors. In a period of low inflation, the fees charged by hedge-fund managers absorb a large proportion of nominal returns…one academic reckons the hedge-fund take can be as much as 40% of portfolio returns. That makes it hard to see how the process can be worthwhile for the client. Of course, this system is extremely good news for the managers themselves. Hedge-fund titans regularly top the list of the great earners [of the world], thanks to the performance fees that kick in when they do well.

And as for the social outcomes being offered up by lawyers and accountants, well, all I have got to say on this topic can be conveyed briefly by referring to some of my earlier posts on Enron, and tobacco litigation. (I will defer my comments on the state of U.S. healthcare to another time.)

What’s the Impact of All This Reward & No Risk for The New Class on Everyone Else?

Pondering on all this, one day I was struck by a strange thought. If this new class has been steadily increasing its share of the rewards of the U.S. economy while refusing to absorb any of the risks, what impacts has this had on, well, everybody else? How are those outside the golden circle of the New Class faring?

The data of Mssrs. Dew-Becker and Gordon in the paper referred to above suggest that the New Class has not been very good at sharing with the other children in the sandbox:

Our most surprising result is that over the entire period 1966-2001, as well as over 1997-2001, only the top 10 percent of the income distribution enjoyed a growth rate of real wage and salary income equal to or above the average rate of economy-wide productivity growth. Growing inequality is not just a matter of the rich having more capital income; the increasing skewness in wage and salary income is what drives our results.[emphasis added]

Dean Baker summarizes the impact of the New Class on the rest of the economy (in a piece you can read here):

The country has seen a sharp growth in inequality over the last quarter century, as most workers have seen almost no increase in their wages even though productivity has increased by more than 70 percent…While there was a redistribution from wages to profits in the 80s and 90s, the upward redistribution that has kept most workers from benefiting over the last decade has been entirely from workers at the middle and bottom to workers at the top. In other words, the reason that autoworkers, teachers, and dishwashers are falling behind is that doctors, lawyers, CEOs and college presidents are walking away with so much of the pie.

BTW, the upward redistribution from wages to profits in the 80s and 90s that Mr. Baker refers to was as we have seen above was modest and temporary; remember that the long term rewards to capital appear actually to have trended downward over the past 50 years. (I’ll be getting back to that important point in a future post).

Well, if the rest of society has done poorly on the reward front, how is it doing on the risk side of the equation? While bankruptcy data is by no means a perfect measure of such things, I think that it is at least suggestive. Elizabeth Warren, a Harvard Law School professor comments in her 2002 paper: Financial Collapse and Class Status: Who Goes Bankrupt? (which you can read here) certainly suggests that downside risk remains alive and well in the U.S.:

From 1991 to 2001, the number of households filing for bankruptcy in the United States rose by 66 per cent. This jump was all the more remarkable because it occurred during a long-running economic boom that yielded record profits on Wall Street, low unemployment, and negligible inflation.

According to Ms. Warren, the risk of financial collapse has not only risen, but is by no means concentrated at the very bottom of the pile:

These data [on occupation, education, and home ownership] make it clear that the sharp rise in bankruptcy filings cannot be attributed to a large number of chronically poor debtors (people with no skills and no prospects) who end up in financial collapse. The data presented here make it clear that, whatever their current economic circumstances, the families in bankruptcy share many of the same educational, occupational, and home buying experiences as other middle-class Americans. [Emphasis added]

But that does not mean the risk is distributed equally; oh, no:

[T]he proportion of workers who are sales clerks and construction workers is about the same in bankruptcy as it is in the general population…There remains a pronounced divergence at the very top, with doctors, lawyers and aeronautical engineers markedly under-represented in bankruptcy [relative to their numbers in society]. [Emphasis added]

Yep, those risk-averse New Classers definitely know something the rest of us do not. But what is it? How do they so successfully defy the risk-reward curve? How do they float above the rest of us earth-bound types?

I will be poking into that topic in my next post.

Cheers,

Friedrich