The conventional wisdom already emerging on America’s political Left is that the Tea Party movement “cost the Republican Party a Senate majority.” That may or may not be true, but one thing we can be sure of: The Tea Party handed the GOP “establishment” two victories Tuesday night.

The first victory is obvious. Republicans now control the US House of Representatives and are in stronger position to filibuster Democrat proposals in the US Senate. They’re in the best of all possible political positions. They can pass “smaller government” legislation in the House, knowing that it will never become law. If it doesn’t die in the Senate, President Barack Obama will veto it. And when they pass the “bigger government” legislation that both parties really want in both bodies, they’ll tout their “bipartisanship” to moderates and complain to conservatives that “we had to get something done that the President would sign; this was the best we could do.”

The down side for Republicans is that Tuesday’s election almost certainly presages a trip to the wilderness for them in 2012 — loss of their sparkling new House majority and re-election of Obama to the White House … but that’s okay. They’re political Keynesians, focusing on the short term because in the long run they’re all dead anyway.

The GOP’s second victory is over the Tea Party itself.

As I write this, the Tea Party’s success in Republican primaries this year appears appears to have blown GOP Senate pickups in Delaware, Colorado and Nevada, as well as costing it a seat it previously held in Alaska. And while the Tea Party candidate didn’t win the US Senate primary in California, anti-Tea-Party backlash was part of what put Democrat Barbara Boxer over the top against Republican challenger Carly Fiorina.

There will be more Republicans in the Senate come January than there are now, but the new guys aren’t the Tea Party’s people. The “establishment” GOP leadership remains firmly in control of the Republican Senate caucus and of the party itself. That leadership began signaling last week, before the votes had even been cast and counted, that it intends to “govern toward the center, not the Right.” The Tea Party wave has crested. It will break on the rocks of the 112th Congress.

To those who disagree when I say that nothing substantial has changed, I propose a test case to watch:

In January, Congress will vote on whether or not to raise the federal government’s “debt ceiling” so that it can continue borrowing money and spending more than it’s taking from tax revenues. I hope we can agree that “real change” implies, at a bare minimum, balancing the checkbook. I predict that we’ll see no such change. After some theatrical bellyaching and grandstanding, they will indeed raise the “ceiling.”

If you voted on Tuesday, you voted for continued operation of the state — and that’s exactly what you’re going to get. But let’s learn a little something from it, shall we?

Debate over the meaning of “Left” and “Right” in a political context has raged for a couple of centuries now, but this campaign cycle has given me a new understanding of the terms that I’d like to share with you. Some think that “Left” means “bigger government” and Right means “smaller government.” Others think that the “Left” values “change” while the Right values “tradition.”

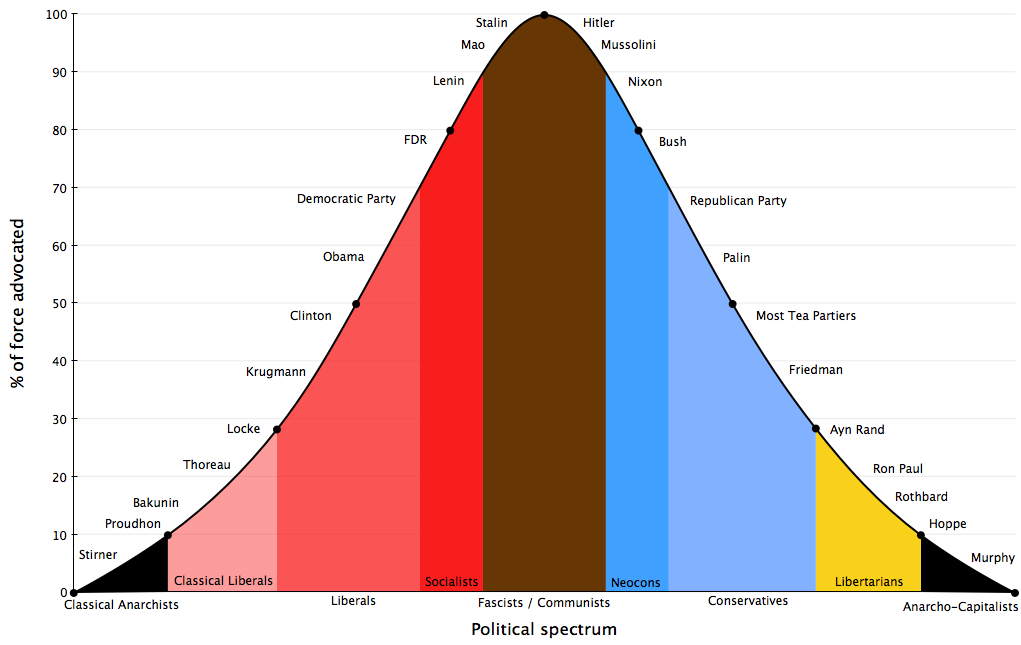

I propose that we look at politics as a bell curve.

I propose that we look at politics as a bell curve.

On the far Left (market anarchism) and the far Right (anarcho-capitalism), appetite for political government trails off to zero (which is why “Left” and “Right” libertarians have so much in common).

As we move toward the political center, that appetite grows. The “Left” and “Right” disagree on ends, but closer to that center, both see government as an acceptable means to their desired ends. And the center is a corrupting influence. As you get closer to it, you grow less willing to give up the means and more willing to give up the ends.

The “Tea Party Right” is approximately analogous to the “Progressive Left.” It’s stranded in the no-man’s land between principled edge and corrupt center. This would make both movements completely useless to anyone except that the center is so large that it generates its own sort of “gravity.” From their positions within the center’s gravity well, these movement lend mass and momentum, in the form of votes and activism, to the center itself.

The state is its own end. It cannot be used against itself. The Tea Party movement tried to create a new political world. It succeeded only in becoming another moon yoked in lifeless orbit around the old one.